Andrew Battel was a failed English pirate. Captured by his intended victims, he was forced into convict labor by Portuguese colonial officials in Angola, Africa. He then went on to a varied career as a Portuguese soldier, a weird sort of half-merchant-half-mercenary dude, a minor warchief, a soldier again, and finally a deserter. His and his comrades’ story makes a really interesting template for enemies you can use as mooks supporting whatever villain your RPG campaign needs.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

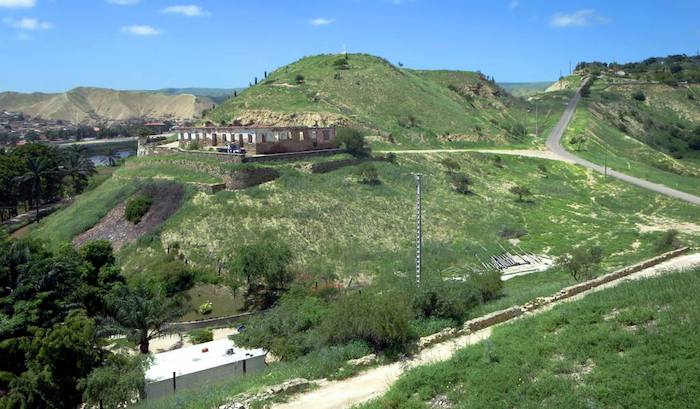

Image credit: jlrsouosa, released under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

Andrew Battel was a mariner from Leigh-on-Sea in southeast England. In 1589, he left England to be part of a small pirate expedition raiding and slaving along the Gulf of Guinea. This was a part West Africa that Portugal was attempting to dominate, having arrived at the colonial conquest party before the larger European nations. The Portuguese drove off the pirates, who opted to try their luck raiding Portuguese Brazil instead. There, Battel was captured. The Portuguese shipped him to Angola. They kept him as a prisoner and put him to work all along the African coast, sometimes as a sailor, sometimes as a soldier. During this phase of his memoirs, Battel’s language shifts, suggesting to me that he may have stopped being a convict. He wasn’t free per se. He’d still be hanged as a deserter if he fled. But he seems to have been no less free than any of his comrades.

In 1600 or 1601, Battel was a sailor on a Portuguese trading expedition along the coast of Angola. The expedition spotted a great camp at the mouth of the Cuvo River where no camp had been seen before. The sailors went ashore to talk. These people – the Imbangala – were new to the Portuguese. They may have come from an inland state that had been conquered by another, pushing the Imbangala towards the coast. Displaced from their own homeland, the Imbangala had become a wandering military power, burning towns, kidnapping people, and forcing them into slavery.

This suited the Portuguese just fine! The Imbangala had enslaved so many people that the Portuguese could buy them real cheap. The sailors filled their holds with enslaved Africans in only a week trading with the Imbangala, buying people at one-twelfth the price they could sell them for in the capital of Portuguese Angola. The Imbangala general, Imbe Calandola, saw that the Portuguese could be a big help to him. Not only would the Europeans buy his merchandise, they had gunpowder weapons – not available in these parts. So before the Portuguese expedition left, he asked their captain if they wouldn’t mind doing the Imbangala a little favor.

Across the Cuvo River from the Imbangala camp lay the Kingdom of Benguela. General Calandola had his heart set on Benguela as his next target. But the army of Benguela was drawn up on the other side of the river to keep the Imbangala from crossing. Could the Portuguese do Calandola a favor and help his people cross under fire? The Portuguese were only too happy to lend a hand. After all, the ensuing violence would generate loot and slaves, which Calandola would want to sell and the sailors would want to buy.

So Andrew Battel and the rest of the Portuguese expedition landed on General Calandola’s side of the river. They brought the ship’s boat with them and made rafts. From daybreak to noon, the sailors shuttled Imbangala soldiers across the river. They used their muskets to drive off the Benguela soldiers so their Imbangala allies could land. Many Imbangala soldiers were killed in the fighting on the far side of the river, but General Calandola was victorious in the end. He slew the Benguela prince, Hombiangymbe, and seized all the spoils of his country. And he couldn’t have done it without the help of Andrew Battel and those with him.

Calandola plundered Benguela for five months. During those five months, the expedition Battel was part of returned three times to the capital of Portuguese Angola to sell the booty they’d purchased from Calandola, especially people he’d kidnapped and forced into slavery. But when they returned after the third trip, the Portuguese expedition found Calandola had marched his forces inland, looking for fresh lands to plunder.

Battel’s masters didn’t want to lose their meal ticket. So they anchored the ship and sent fifty men (including Battel) inland after General Calandola. Their trail led them to lord named Mofarigosat, who was rebuilding a city General Calandola had burned. Lord Mofarigosat couldn’t stand up to the Imbangala, but he could absolutely stand up to fifty Europeans, muskets or no muskets. The Imbangala were still in the area, and Lord Mofarigosat wasn’t going to let the Europeans through to join up with their friend Calandola until after the Imbangala had left and would trouble Lord Mofarigosat no more.

Once the Imbangala had moved on to greener pastures, Lord Mofarigosat still delayed. Like General Calandola, he found it useful to have a gang of musketeers on staff. So Mofarigosat led the Europeans out on raids against his enemies, crushing them one by one. Andrew Battel may have briefly been a merchant sailor, but he was once again a convict soldier – just now for an African power, not a European one. The expedition desperately wanted to leave Lord Mofarigosat’s service, but he wouldn’t let them go without a hostage. They chose Battel – the only Englishman – for the role. They promised Mofarigosat they’d be back within two months, and scarpered back towards the coast.

Battel still had musket, powder, and shot. While waiting for the Portuguese return that would never come, Lord Mofarigosat gave Battel progressively greater liberty to wander his lands. Battel seized an opportunity to flee Mofarigosat’s service. He picked up the trail of General Calandola and the Imbangala and pursued them until he finally caught up.

Battel and the Imbangala traveled west along the Cuanza River to make war against a leader named Cafuxe. Cafuxe was no lightweight; he’d defeated the Portuguese in battle some seven years earlier. The war against Cafuxe lasted four months. During that time, Battel claimed he rose to prominence among the Imbangala for his skill with his musket. He claimed General Calandola put him in charge of his men and would give him anything he asked.

The war was only three days from a Portuguese fort on the Cuanza River. The Portuguese sent men from the fort to the Imbangala camp to buy slaves. Battel took advantage of the opportunity to accompany one of these expeditions back to Portuguese custody. He apparently preferred to take his chances with his former jailers rather than remain in service to General Calandola. It had been a year and a half since his comrades had left him behind as a hostage of Lord Mofarigosat.

The Portuguese slipped Battel right back into the army as if nothing had happened. They even promoted him to sergeant. Battel marched with Portugal to make war on other African nations. Around 1606 or 1607, after about two years of this, Battel conspired to desert. He snuck away, made a canoe, rigged a blanket as a sail, and set out to sea. There he encountered a ship whose captain he knew from his sailing days. The captain picked Battel up and took him as far as the kingdom of Loango, in what is today the Republic of the Congo (Congo-Brazzaville). There, he remained for three years as a guest of the king.

In 1610, Battel returned to England, settling in his home village of Leigh-on-Sea. He spoke frequently with the vicar of a nearby village and left the vicar his papers when he died. The vicar included Battel’s accounts of his travels in an encyclopedic collection of travelogues published in 1625. This account is (to my knowledge) the oldest surviving written document about the interior of Angola, and is an important primary source. Sadly, the vicar felt the need to alter Battel’s accounts to bring them into line with other (less accurate) European reports from the Congo. So even though Battel’s account is our best source for some important Congolese and Angolan history, we know that some of the facts in it are made up – but not which ones.

Obviously at your table, Andrew Battel and General Calandola are the bad guys. They’re roving through nations, killing, looting, burning, and slaving as they go. Ordinarily we might say “but Battel started out as a convict soldier, so maybe he’s just making the best of a bad situation”. That argument might carry some weight, except he was only in that bad situation because he tried being a pirate.

Battel and his comrades make great enemy NPCs; just file the serial numbers off them and drop them into your ongoing campaign. They’re a cadre of technologically-superior mercenaries that you can add to the retinue of any bad guy you were already planning to use. Except they’re not mercenaries the way your players are accustomed to. Instead, they’re merchants (and convicts being made to work for merchants) lending a hand to your bad guy with the understanding that they get to buy the loot the bad guy generates, then resell it at a twelve-fold profit.

And that twist is interesting! Beefing up your bad guy with mercenaries is already fun, because the mercenaries can be really distinct from the rest of your villain’s mooks, and the PCs can pay off the mercenaries as well as killing, outmaneuvering, or intimidating them. But these mercenaries don’t see themselves as mercenaries. You can get rid of them by finding them better trading opportunities elsewhere, appealing to their superiors in their own nation, or tanking the market of the goods they were planning to sell. And you always want there to be lots of ways the party can approach a given problem – the more the better!

Plus, Andrew Battel makes a great NPC captain of these not-really-mercenaries, especially towards the end of his career with General Calandola. He’s been a pirate, a convict, a merchant, and now a war-leader. He’ll be real neat to roleplay with, if you can just find a way for him to talk to the PCs one-on-one.

Check out my book Making History: Three One-Session RPGs! It’s three awesome historical one-shots with pregenerated characters and a very simple rules system designed specifically for that story. Norse Ivory is a game about heritage and faith in the Viking Age. A Killing in Cahokia is a murder mystery in the Native American temple-city of Cahokia. And Darken Ship is a horror-adventure starring junior sailors on a U.S. Navy warship who wake up one morning to discover they’re alone on a ship that should carry three thousand.

Source: The Strange Adventures of Andrew Battell, Reprinted from “Purchas His Pilgrimes”,edited by E.G. Ravenstein (1901)