In 1924, in Guangzhou, China, six bandits kidnapped thirty-six students and staff at an agricultural college. What might otherwise be a pretty simple story of retrieving some hostages gets incredibly muddy with just a little bit of context – and the whole thing makes a great RPG adventure!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. He also really helped me out with some information on Li Fulin and the KMT, discussed further below. Thanks, Colin! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

The first half of the 20th century saw several attempts to share agricultural knowledge between the U.S. and China. Some American investigators traveled broadly in China observing agricultural practices and collecting unfamiliar cultivars. A few American scientists founded or worked in Chinese colleges. And some Chinese students attended agricultural colleges in the U.S., where they learned American techniques and shared Chinese ones. Little came of these efforts. There were two reasons why.

The first was that Chinese and American needs were very different, and both were already pretty good at meeting those needs. American farms were large and labor expensive. With so much room for farming following the conquest and genocide of the Native nations of the West and Midwest, Americans had more land to farm than they knew what to do with. This was the perfect situation for mechanization: the use of expensive machines that could do the work of many men. But Chinese farms were tiny (sometimes as small as half an acre) and labor cheap. Big machines were worse than useless. Instead, Chinese farmers excelled at micromanaging their land with techniques unsuitable for American farmers plowing hundreds of acres. Even new, higher-yield American crops found little traction in China: when your tiny farm was barely big enough to grow enough to feed your family, you couldn’t gamble on planting an unfamiliar crop.

The second reason these information exchanges failed was political. Chinese farmers had good reason to dislike and mistrust foreigners. A long series of invasions by foreign powers generated so much resentment that much of China rose up in the anti-foreign Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901). Eight foreign powers responded with overwhelming force; punished the rebels, the government, and the people; and deepened Chinese resentment. After the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1912-ish, the new Republic of China found it useful to stoke anti-foreign sentiment. How much (or how little) of the country the government controlled – and which faction ran the government – shifted from year to year and even month to month. Encouraging anti-foreign sentiment was a way to get people to pull together and to convince them you were on their side. Two of the more powerful factions (the Communist Party and the ‘nationalist’ KMT party) framed China as going through a so-called Century of Humiliation imposed on it by the outside world. Thus, even in agricultural arenas where American techniques were helpful (like pest control and artificial fertilizers), local authorities couldn’t be seen as collaborating too closely with foreigners, lest they offend people and populations whose support they desperately needed.

In 1908, an American missionary named George “Daddy” Groff arrived in Guangzhou. He was supposed to teach middle school at a Christian college. But his degree was in agriculture, so he also started a gardening program. Four years later, the school formally added gardening to its curriculum. Groff believed that missionaries could teach American agricultural techniques and Christianity side-by-side, and if they succeeded in improving crop production, the grateful Chinese would open up to Christianity.

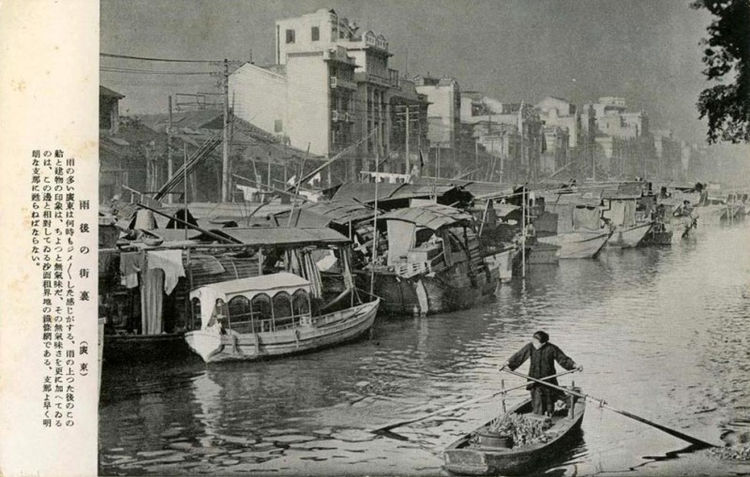

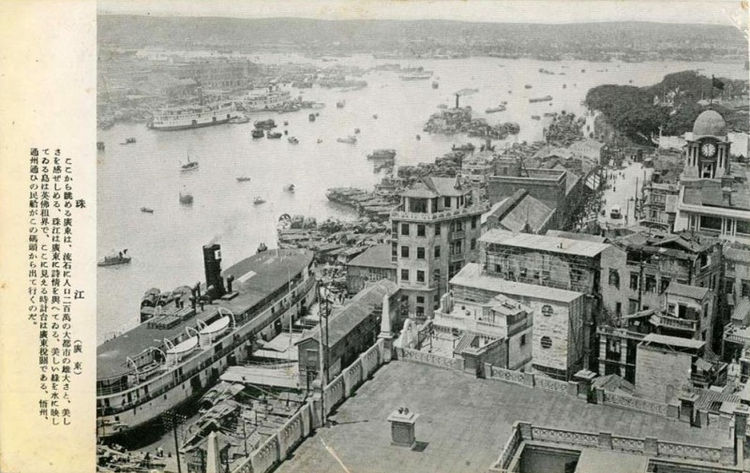

Daddy Groff (that’s really what he went by) strove to add an American-style agricultural extension to the Canton Christian College. He didn’t have much luck getting funding from the college or from missionary boards back in the States. He did manage to consistently scrape together a few bucks from his alma mater, Penn State. With this shoestring budget, Groff was able to operate an experimental farm on the same island in the Pearl River as the college. He had students, though never many. His greatest agricultural accomplishment was probably the introduction of the Hawaiian papaya, which came to be grown across southern China. Groff never really grappled with the fact that most of what he could teach wasn’t applicable to China, and that few people wanted to listen to him anyway. He was pedaling furiously but wasn’t going anywhere.

In 1924, some of the college’s students were kidnapped! Folks transited between the college’s island and Guangzhou by ferry. Six bandits boarded the ferry dressed as “ordinary Chinese gentlemen”, but when the ferry was in midstream, they commandeered a nearby launch and made off with thirty-six students and staff. They retreated to the Guangdong countryside. The bandits demanded the equivalent of $150 ($2,400 today) per hostage for their safe return. Parents and friends of the kidnapping victims flooded the college to offer their opinions. As usual in these cases, the debate was over whether to pay the ransom and, in so doing, encourage future kidnappings.

Enter an old friend of Groff’s agricultural college: General Li Fulin, governor of Guangzhou. Li maintained his own orchards and was interested in Groff’s research. Li was also a senior member of the KMT faction within the Republic of China. By 1924, the KMT (roughly ‘Chinese Nationalist Party’) was built around a flexible, practical ideology that’s hard to easily communicate outside its particular time and place. Its ostensible three pillars were nationalism, democracy, and welfare – but also kind of not really. In 1924, you could find representatives of just about every political ideology (including none) under the KMT banner. Patreon backer Colin Wixted, whom you should trust more than me, called the KMT’s ideals in this period “Lincoln and Lenin in a blender”.

At the time, the KMT controlled much of the south. A rival government in Beijing controlled much of the north and was run by a constantly-shifting alliance of regional warlords. Other shifting coalitions of bandit warlords governed other parts of the country, most notably (to this post) in Yunnan, west of Guangzhou. Li Fulin had gone to war with the Yunnan warlords in the past.

Li was in a tricky spot. He couldn’t tolerate banditry and kidnapping of well-connected people in his city. But neither could he risk appearing too pro-foreign. Guangzhou and the surrounding Guangdong province were not solidly in KMT hands. If he came across as incompetent or unacceptably pro-foreign, one of his subordinates might depose him and turn to Yunnan, Beijing, or even the rest of the KMT for backing. It was a chaotic time.

But Li pulled it off! Instead of going after the bandits directly, he went after village leaders. He contacted all the village heads in the general area to which the bandits fled. He told the leaders he’d hold them responsible for whatever happened to the hostages. I have no idea the severity of the implied threat. Fines? Summary executions? Regardless, the village leaders got the job done. Where Li had only hard power in the countryside, these guys had soft power: local knowledge, family connections, public pressure. The bandits coughed up the hostages.

So we’ve got these two colorful NPCs (Daddy Groff and Li Fulin) and a bandit hostage crisis. Let’s throw in one more complication. In 1924, American missionary organizations saw themselves as being in direct competition with the KMT in the field of agriculture. A 1922 missionary report called The Christian Occupation of China (a bit on the nose in the naming department) reflected a growing consensus in favor of the position that Groff had long advocated: that the way to the heart of China’s farmers (the vast majority of the population) was through agricultural assistance. The missionaries wanted to build a network of ag extensions across KMT-held China to help farmers implement new agricultural techniques that would improve their lives and make them receptive to the Christian message.The trouble with this hoped-for ag extension network is that missionaries saw it in opposition to the KMT. Americans necessarily viewed ag extensions as a government function; the USDA had been running such a program for a decade. So the missionaries working to set one up in China saw themselves as actively usurping a government role. Plus, the KMT wanted to build their own ag extension network. They just didn’t have the money for it, what with their constant wars against the warlords. Indeed, the KMT wouldn’t start its unimpressive program until 1931. Of course, the missionaries’ hoped-for rival ag extension network didn’t really materialize either. Turns out it was hard to find American Christian technical experts who wanted to work for pennies in austere conditions in rural China instead of taking good jobs in the States. But the point was that these agricultural missionaries and the KMT saw one another as competitors in the quest to improve productivity on Chinese farms.

The tension between the agricultural missionaries and the KMT doesn’t seem to have affected Li Fulin’s quest to return the hostages, but it certainly lends the event an interesting color.

At your table, you can fictionalize this bandit hostage mini-incident and turn it into a really interesting adventure the PCs have to handle delicately. If anti-foreign sentiment isn’t present in your campaign’s fictional setting, find another reason for folks to dislike your Groff-analogue, like people not liking the religion he’s pushing. If there’s not a faction/civil war thing going on, make your Li-analogue’s position unstable for other reasons, like poor performance in his previous role or bad poll numbers. And if agricultural extensions don’t make sense as something for Li and Groff to jockey over, find some other public service that Li’s government wants to provide but can’t, so Groff tries to provide it instead.

Of course, you’re not going to want your Li-analogue to waltz in and solve the problem of the bandit hostages the way he did in real life. That’s the PCs’ job! So make your version of Li unable to resolve the hostage problem due to circumstances entirely beyond his control. Maybe he’s overseeing a military action and can’t spare any attention or resources to pressure the bandits to release the hostages. Because your Groff-analogue can’t turn to the KMT, he instead has to turn to the PCs.

Depending on the party’s resources, they might not be able to replicate Li’s real-life strategy of holding village heads responsible. It’s more likely they’ll have to track the bandits into the countryside and then negotiate for the release of the hostages or lead a daring rescue. But how they approach this task impacts their relationships with Li and Groff. Do the PCs introduce themselves at the negotiation as intermediaries hired by Groff? Li’s not likely to appreciate the party making him seem uninvolved. Do the PCs raid the bandit compound dressed in KMT livery? Groff may be grateful for the return of his people but wonder why the party had to make his friend/rival look good in the process. If the party makes a real mess of the situation, it might even draw the attention of some of the bigger factions.

Then you can base your next adventure on the relationships the PCs ruin and build in this adventure! Parties that anger your KMT-analogues may find themselves recruited by your unsavory analogues of the Yunnan faction. Parties that anger Groff may be targeted by influential America-based missionary boards. This is a pretty short adventure, but you can use it as a springboard to longer ones if you like!

–

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Facebook, I’m Molten Sulfur Press.

Source: The Stubborn Earth: American Agriculturalists on Chinese Soil 1898-1937 by Randall E. Stross (1986)