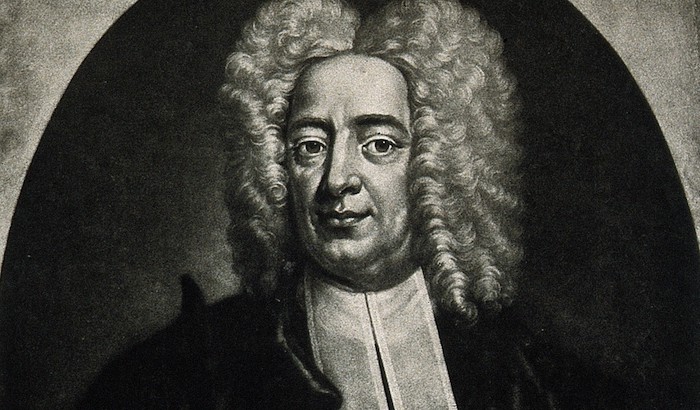

The Puritan clergyman Cotton Mather (1663-1728) is one of the boogeymen of early American history. Among his many sins, he helped fuel the Salem witch trials that executed 20 people for witchcraft. In the trials he successfully argued that the contents of magical visions should be considered legally admissible evidence. Mather was a prolific writer. His religious history of New England, the Magnalia Christi Americana, contains many stories of witchcraft, demon possession, and hauntings. It’s a weird text to read. On the one hand, it contains several ghost stories very suitable to adapt and put into your campaign as adventures. On the other hand, this dude’s response to those very same stories wasn’t “these are chilling and entertaining make-‘em-ups” but “I believe so deeply these tales are true that I’m going to help execute twenty innocent people”. Indeed, the same chapter that includes these ghost stories also includes his chosen version of the history of the Salem witch trials. We’re going to talk about three cool ghost stories and about their relationship to Mather’s bloody hands.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Image credit: Wellcome Images, released under a CC BY 4.0 license.

These ghost stories are part of a broader collection of tales of devils, hauntings, and witches that Mather intended should warn the reader about the dangers posed by the Devil. Mather believed devils preferred to dwell in the wilderness, far from where prayers to the Christian God were offered. In Mather’s eyes, that wilderness was North America. The continent’s indigenous nations didn’t weigh against it being a wilderness, for – while Mather elsewhere acknowledges their princes and their cities – he viewed Natives as barbarians, idolators, and inferiors wholly disconnected from Christ except through forcible conversion. So devils lived in Native cities as freely as they did in the forests, and periodically crept into Christian villages to cause harm. The ghost stories Mather credulously regurgitates are thus intended not as entertainment but as evidence to support a worldview (already discarded in most of Europe) of an omnipresent darkness pressing in against tiny candles in the night. If you want to explore that aesthetic at your table I’d point you at Free League’s Symbaroum or the Points of Light setting in 4th edition D&D, rather than setting it in a time and place where the ancestors of currently-marginalized people were part of that perceived darkness.

For our first ghost story, I’ll mostly quote Mather, though I’ve updated his language and dropped a few uninteresting details:

“In June 1682, Mary, the wife of Antonio Hortado, dwelling near Salmon Falls, heard a voice at the door of her house, calling “Why are you here?” About an hour after, she received a blow on her eye that almost killed her. Two or three days later, a great stone was thrown along the house. When people went to move it, it was unaccountably gone. Mary and her husband, crossing the river in a canoe, saw the head of a man and the tail of a cat separated by three feet with no body between them, seeming to swim before the boat. The same apparition again followed the canoe when they returned, but at their landing it disappeared. A stone thrown by an invisible hand caused a swelling and a soreness in Mary’s head. Her breast was scratched. She was bitten on both arms black and blue, leaving the impression of teeth like a man’s, being seen by many.”

“The Hortados deserted their house. At a neighbor’s, they were at first haunted by apparitions, but the Satanic aggravations soon ceased. When Antonio returned to his own house, he heard someone walking in his room and saw the boards buckle under the feet of the walker, yet there was nobody there. So he went back to live on the other side of the river. But thinking he might still plant his fields even though he’d left his house, he had 25 yards of good log fencing erected. Nonetheless, he saw the hoof-prints of cattle between almost every row of corn in the field, yet no cattle were seen there, nor any damage done to so much as a single leaf on his crop.”

In a gaming context, I’d interpret this as a haunting by a single weird monster that can turn part or all of itself invisible. It walks on two legs and swims with four. It has the head and hands of a man, the feet of an ox, and the tail of a cat. It develops an unaccountable hatred for some people and is merely creepy to others. That’s why it threw rocks at, bit, scratched, and punched poor Mary Hortado but largely left Antonio alone.

You can have NPCs based on the Hortados approach the PCs and beg them to do something about the haunting at their house. They’ve fled to their neighbors, but can’t stay there forever. Mary is badly hurt, but Antonio is just scared. If the PCs visit the abandoned homestead, they find evidence of the creature’s presence: cow hoofprints in the cornfield with no corn damaged, and a gouge in the earth where a boulder was thrown, then removed. Pick a PC whose player would particularly enjoy (and be creeped out by) being the target of the monster’s ire. Have it chuck a stone at him. Hard. The PCs can go around the homestead collecting clues, but whenever this PC is left vulnerable, he gets punched or bitten. When he’s protected, the monster finds other ways to torment him, like leering through a window or driving nails up through the floor beneath.

And that’s the best way to defeat this monster and end the haunting: use its obsession with the singular PC to lure it out in the open, trap it, and kill it. Once the PCs realize they’re dealing with a singular corporeal, invisible entity, they can grab the creature! Remember that it might be listening in on their plans, though, and might change its tactics accordingly.

Next we have a cursed sea voyage from Boston to Barbados – not that the ship ever arrived. On December 28, 1695, the ship Margaret left Boston with a crew of nine and a single passenger. Within a few days, sailor Winlock Curtis declared he had been visited by a spirit that accused him of killing a woman and would take him away soon. It also told him the rest of the crew had signed the Devil’s book (placing themselves in thrall to Satan) and that he should too. Curtis denied killing the woman and told his shipmates he would never sign the Devil’s book, no matter what they might do. He was relieved of his duties. The next day, Curtis was thrown upon the deck by an invisible hand and strangled until his face turned black. As he recovered, he spoke of visions in the air and how a spirit was coming for him with a small boat. He tried several times to leap overboard to join the spirit, so his shipmates tied him up. He fell asleep, slept for twenty-four hours straight, and then seemed much better.

Then on January 17th, a small white cloud fell upon the Margaret with no other wind or rain, and laid her down on her starboard beam. The ship filled with water and would have sunk had it not been carrying a load of timber. Instead it was just buoyant enough to wallow with its deck even with the waves. The pumps were broken, so the crew nailed two planks across the rail, stretched a sail over them as a tent, and lived up there while the broken ship limped its way agonizingly towards land. Then the passenger started to talk funny. He said a man he was supposed to meet in Barbados was standing at the base of the mainmast with a small boat and had come to take him away. A few days later, the passenger disappeared without explanation. Two weeks later one of the crew disappeared similarly, then the sailor Winlock Curtis. Two weeks later, two more sailors disappeared without a trace. These disappearances were accompanied with noises like birdsong. The remains of the Margaret ultimately landed on Guadeloupe.

At the gaming table, I love the idea of a spirit in a small boat who comes to take people off ships in the middle of the night. It’s very creepy! She’s accompanied by birdsong because why not and accuses people of crimes they may or may not have committed. She’s a fabulous way to spice up a long journey. On overland trips, she appears on horseback accompanied by a second horse with an empty saddle – that’s for you! One by one the PCs’ traveling companions disappear unless the party takes active measures to prevent it. Any active measures will do (reward creativity) and triggers a confrontation between the spirit and the PCs. Maybe she even suggests the PCs play a game of chance or skill against her. If the PCs win, she returns the people she’s taken. If she wins, the party must go with her. As long as the PCs don’t lose such a game, this isn’t a full adventure, but it’s a fun interlude on a long trip. If they do challenge the spirit and lose, though, they are taken to hell and have to find a way to escape. This post from 2018 feels appropriate for that adventure, though since it’s more than a year old, it’s behind a (very cheap!) Patreon paywall.

Finally, we have a remarkably detailed poltergeist case. In 1679, the house of William Morse in Newberry, Massachusetts, was beset by a long list of terrible phenomena. Quoting from (and modernizing) Mather again: “Bricks, sticks, stones, and pieces of wood were by some invisible hand thrown at the house. A cat was thrown at the woman of the house. A long staff danced up and down in the chimney. When two persons laid it on the fire to burn it, it was as much as they could do with their joint strength to hold it there. The doors were barricaded and the keys of the family were taken. The people of the house could not eat dinner quietly, but ashes would be thrown into their suppers and on their heads and in their clothes. When they were abed, a stone weighing over three pounds was often thrown upon them. The invisible hand took a bag of hops out of a chest and beat the family with it. … The invisible hand pricked the man with some of his awls, with needles, with bodkins, and blows. … When his wife went into the cellar, the invisible hand laid a table upon the trap door to keep her down there until her husband removed it.

“A little boy belonging to the family was a principal sufferer in these events, for he was flung about at such a speed they feared his brains would have been beaten out. His parents could not hold him. … The man put him in a chair, but the chair started to dance and both were very nearly thrown into the fire. So the parents took the boy to live at a doctor’s. … But his troublers found him there also and stuck him with an iron spindle, pins, a long iron, and all the knives of the household. The poor boy was often thrown into the fire. … He complained that a man called ‘P––l” appeared to him as the cause of all. Once in daytime the boy disappeared, and no one could find him. At last he was found crawling along the side of the house. He said that P––l had carried him over the top of the house and hurled him against a cart-wheel in the barn.”

Eventually this invisible hand started to become visible. “One time the fist beating the man was discernible, but they could not catch hold of it. At length, an apparition of a Black child showed itself to them. Another time a drumming on the boards was heard, which was followed by a voice that sang ‘Revenge! Revenge! Sweet is revenge!’ The terrified people called upon God. At this came a mournful note: ‘Alas! Alas! We knock no more, we knock no more!’” His name invoked, “it pleased God mercifully to shorten the chain of the Devil,” and the haunting ceased.

At your table, obviously the solution to this poltergeist case can’t just be to invoke the name of God. That’s way too easy. Instead, you’ve got to figure out what act drove an invisible spirit to want revenge upon William Morse, his wife, and especially their son. Asking the Morse family is no help; even if they know, they sure won’t tell you! Figure out the Morse family’s wrong and set it right and hopefully the poltergeist will go away – or at least weaken and become visible so you can fight it. I’m particularly intrigued by the boy’s identification of a man named ‘P––l’. (Mather bleeped out the middle, not me.) A cursory check for well-known demons with a name with that first and last letter turned up nothing. But in 2021, I wrote about a 16th-century Swiss grimoire that mentioned a moon spirit named Phul. That post is behind a paywall now (It’s very cheap! $2 a month for the entire back catalog of almost 300 searchable posts!), but to summarize: Phul is the true name of the moon. He can cure edema, offer spirits of water as familiars, and extend your lifespan. Maybe William Morse’s son practiced forbidden pagan rituals to honor the moon but did it badly, so the moon is offended and sent a spirit of water to punish the child – and the parents to a lesser extent for not raising him better. The Morse family can’t admit this because they’d be punished as heretics. But until you either assuage or banish the moon, this is going to keep happening.

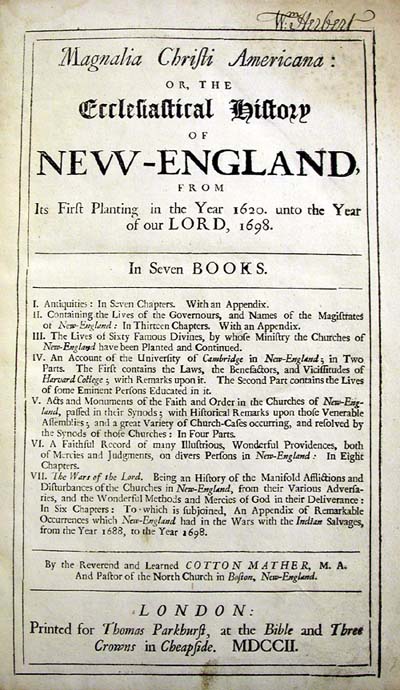

The Magnalia Christi Americana’s chapter on witches, ghosts, and demons concludes with a report on the Salem witch trials, in which Cotton was heavily involved. His most notable contribution was driving through the courts the idea that “spectral evidence” was legally admissible: that victims of witchcraft could report the things they saw, heard, and felt in their visions, and that this constituted meaningful evidence, even if other people in the room at the time of the vision experienced nothing unusual. This was truly weird. Even in the 1600s, English trial evidence centered around eyewitness testimony (“I saw Bill commit the murder”) and material evidence (“here is the knife I saw him use in the murder”). And even in the fanatical Puritan confines of 1600s New England, spectral evidence was soon viewed as too extreme for the courtroom – seemingly because it made it so easy to accuse and convict that soon half the colony might be hanged for witchcraft. Mather’s own father urged the court to give spectral evidence less weight. Before the legal hysteria was drawn to a close, nineteen people were hanged, one pressed to death between stones, and five died in jail.

It’s interesting that in the Magnalia Mather chooses not to give his own account of the trials. Instead, he merely reprints an earlier accounting by John Hale, a minister who helped instigate the witch trials, then turned against them when his wife was accused. Hale’s account unsurprisingly questions whether the trials went too far. One suspects Mather included Hale’s report so as to avoid accusations of partiality in his theoretically-definitive history of religion in New England. If so, I’m not impressed. Mather never solidly recanted his advocacy for spectral evidence. Historians who have attempted to rehabilitate his image seem to argue at most that he was wishy-washy on the subject. If so, his dithering led twenty-five innocents to the grave.

And that inescapably colors these ghost stories. The man who wrote them believed them – really believed them – so deeply that they, and stories like them, drove him to promote mass murder. Does that mean we should not use these stories as inspiration for our gaming tables? I would argue no, it means they are complicated and multifaceted – like everything in real life – and we should treat them as such. And if we’re a little squicked out when we bust them out at the table, all the better. Hopefully that sense of ‘squick’ will rub off on our players, and the feeling of horror will be all the more satisfying.

I had the enormous pleasure of running Shanty Hunters on the Rook and Rasp Twitch channel as part of their series on indie games. The episode is two hours long and a lot of fun. Check it out!

–

I heard about the Magnalia Christi Americana on episode 518 of the podcast Ken and Robin Talk About Stuff. If you read the Molten Sulfur Blog and enjoy it, you really need to be listening to KARTAS. Possibly the best-known game designers outside the D&D space talking about RPGs, history, occultism, time travel, cinema, narrative, art, the Cthulhu mythos, etc, etc. Episode 518 included an overview of Cotton Mather and how to use him as an NPC. The Magnalia was briefly touched on, and I thought to myself, “I gotta read that!”

I used this scan of the copy of the Magnalia owned by Founding Father and second president of the United States John Adams.