Women were not permitted to be soldiers in the American Civil War. Nonetheless, women on both sides adopted male disguises and signed up. In their exhaustively researched book They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the Civil War, historians DeAnne Blanton and Lauren M. Cook claim to have uncovered evidence of about 250 such soldiers. We’ll look at two of them in particular, who both make great inspiration for NPCs.

Women joined up for the same reasons as men: patriotism, adventure, and money (a soldier’s pay was better than a domestic’s). There’s one exception – some women signed up to follow their husbands, from whom they could not bear to be separated. Most women soldiers in the Civil War performed well and ably. That’s no surprise. Women in the Army had to go through a lot of work to get there and stay there. They wanted to be there, and it showed in their performance.

It was surprisingly easy to pass as a man on campaign. Uniforms were baggy. Almost all soldiers slept fully clothed. Harsh conditions and little food probably triggered amenorrhoea. Lots of folks went into the woods to relieve themselves, rather than using the camp’s reeking latrine trenches. Not having a beard despite not shaving wasn’t a giveaway either; there were a lot of beardless teens who’d signed up underage. Not every woman could pass, but for the most part, men saw what they expected to see.

Still, some were discovered. There’s a great quote from a Union colonel writing about a surprise birth, that “a corporal was promoted to sergeant for gallant conduct at the battle of Fredericksburg – since which time the sergeant has become the mother of a child. … What use have we for women, if soldiers in the army can give birth to children?” Discovered women were usually kicked out, though the Confederacy mostly stopped doing that towards the end of the war. They were losing, and couldn’t afford to turn away willing volunteers. The revelation that a soldier was a woman usually didn’t upset her messmates. If you bleed, suffer, and starve beside someone long enough, you stop caring about what genitals they have.

Frances Louisa Clayton (alias Pvt. Jack Williams) enlisted in the Union Army with her husband in the fall of 1861. Her comrades described her as an excellent horseman and swordsman. To conceal her sex, she took up as many masculine vices as she could. She drank, smoked, chewed tobacco, swore, and gambled. She also looked the part. She adopted a masculine stride and erect posture. She was later described as a “very tall masculine-looking woman bronzed by exposure”. Clayton was wounded at the Battle of Fort Donelson, the victory that elevated Ulysses S. Grant to national prominence. Ten months later, at the Battle of Stones River, Clayton watched her husband die just a few feet in front of her. Then the order came to fix bayonets, and she stepped over his body to join the charge.

After her husband’s death, Clayton left the Army and traveled to Washington, D.C. to get the back pay and sign-on bonus she and her husband were owed. Newspapers picked up the story and wrote adulatory pieces about her bravery. People loved Clayton because she conformed to the Victorian storybook notion of the ‘Female Warrior Bold’, an archetype popular in novels of the preceding decades. By contrast, women who joined for money or adventure were often scorned in the press for not conforming to popular romantic themes.

Sarah Rosetta Wakeman had already been living as a man (‘Lyons Wakeman’) for a few weeks before she enlisted. She’d found she could earn more money working as a man handling coal on a boat on the Chenango Canal than at her former job as a domestic. Wakeman grew up on a farm, so she was no stranger to physical labor. Her family knew she was living as a man, and remained in regular contact with her via letters.

Wakeman joined the 153rd New York Infantry in 1862. Judging by her letters, a soldier’s salary was one of her biggest reasons for signing up. She sent much of her money home to help her family get out of debt. Wakeman was very open about enjoying being a soldier. She appreciated the independence (compared to life as a domestic), acquitted herself well in brawls in camp, and took great pride in her skill at drill, her stamina, and her courage. Despite all the hardships of a soldier’s life, she liked earning a decent wage among friends, fighting for a cause she believed in.

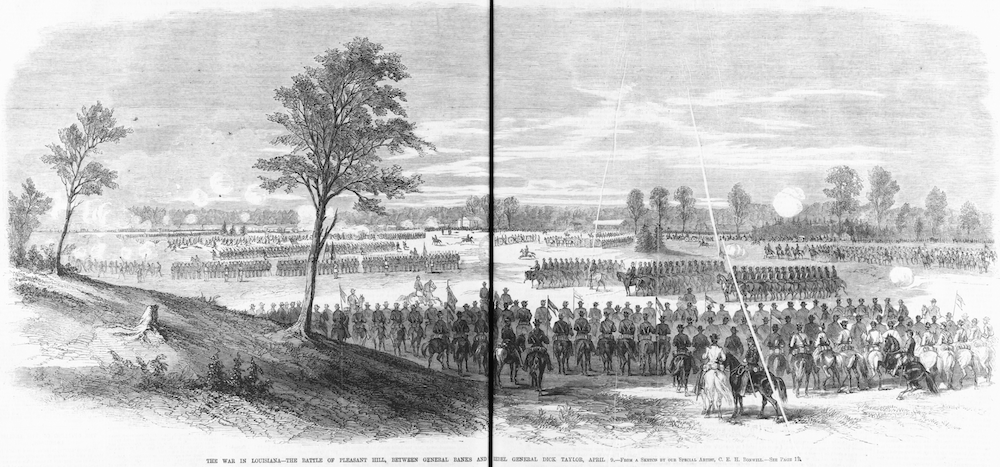

Wakeman fought in the Red River campaign at Pleasant Hill and charged the enemy at Monett’s Ferry. She was indefatigable on the campaign’s endless forced marches and fearless in the face of enemy fire. She wrote to her family that “if it is God’s will for me to fall in the field of battle, it is my will to go and never return home.”

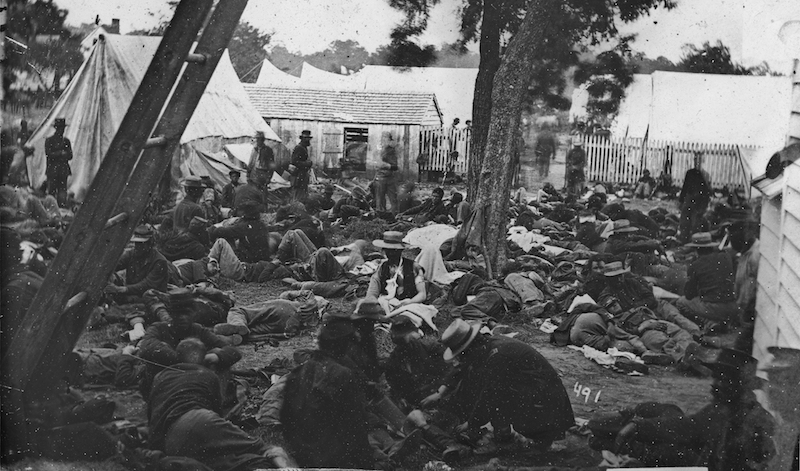

But pestilence is unaffected by the valor of its targets. During the Red River campaign, Wakeman caught chronic diarrhea. The regimental surgeon transferred her to a better hospital in New Orleans, but she never recovered. Sarah Rosetta Wakeman died on June 19th, 1864 at 22 years old. She was buried under her assumed identity of Lyons Wakeman. Twice as many Civil War soldiers died of disease as of wounds.

It’s unclear what happened to Wakeman in her last month of life in New Orleans. She surely became too weak to attend to her own sanitary functions. But there’s no record of anyone discovering her secret, even though nurses and orderlies must have been helping her clean herself. The fact she was buried under her assumed name suggests that her nurses kept her secret.

There are a lot of highly gendered RPG settings out there. I don’t necessarily have a problem with this. Trail of Cthulhu, for example, is set in the 1930s. While the social ills of the era aren’t necessarily what the game is about, they provide a color that’s necessary to evoke the aesthetic of the period. A Song of Ice and Fire Roleplaying is set in a highly gendered world – but it’s also a world that’s fundamentally corrupt, unjust, and cruel.

Clayton, Wakeman, and characters like them inject a little modern color into a less egalitarian setting, but do it without violating the setting’s premise or feeling out of place. They’re colorful, they’re distinctive, they’re memorable, and they have clear and understandable motivations. In short, they’re great NPCs!

Next week, we’ll look at another Civil War female soldier and what she can teach us about making awesome soldier PCs!