Of all the Western explorers in the ‘scramble for Africa’, Henry Morton Stanley was probably the most well-known and highly-regarded. Yet his expeditions had an odd habit of returning with him as the only witness. Let’s take a closer look at this peculiar figure and the bloody, glory-hunting swaths he cut across Central Africa.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Henry Morton Stanley was born John Rowlands in 1841, the bastard child of a Welsh housemaid. He was passed from relative to relative, fostered off on another family, and ultimately dropped off at a workhouse known for sexual abuse. He was six years old. At seventeen, John fled to America, where he adopted a new name, a new identity, and a new nationality. He worked as a sailor and a soldier, fighting on both sides of the American Civil War.

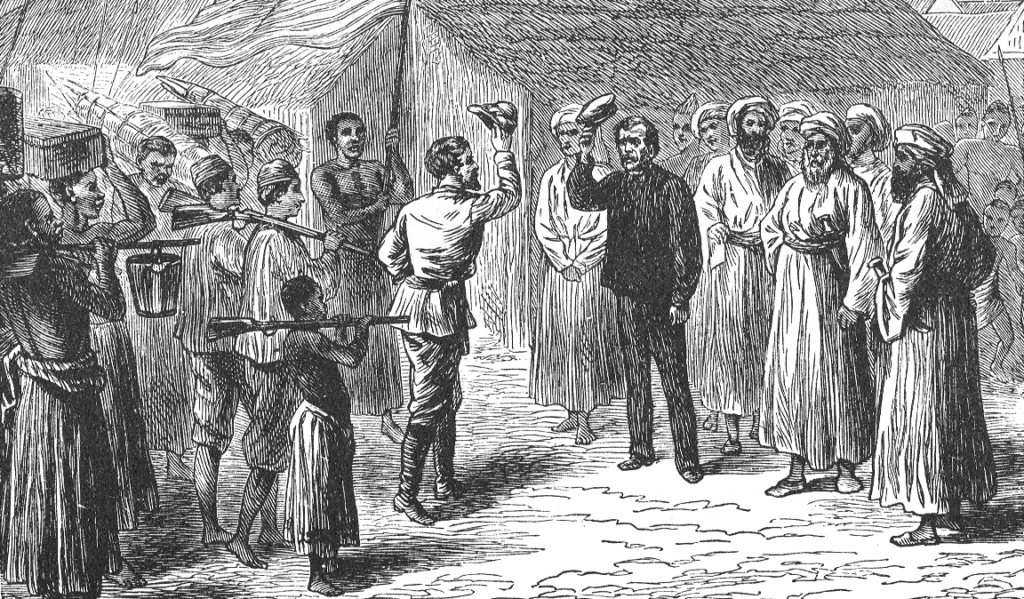

After the war, the newly-minted Henry Morton Stanley found his calling as an itinerant journalist. He sent dispatches from Turkey and the American West. He made his career with a breathtaking scoop in the British war in Ethiopia. And he earned real and lasting fame when he trekked into Tanzania to find the disappeared British explorer Dr. David Livingstone. Stanley’s book about his Tanzania trip was a bestseller. The unwanted bastard child he was born as was dead and buried.

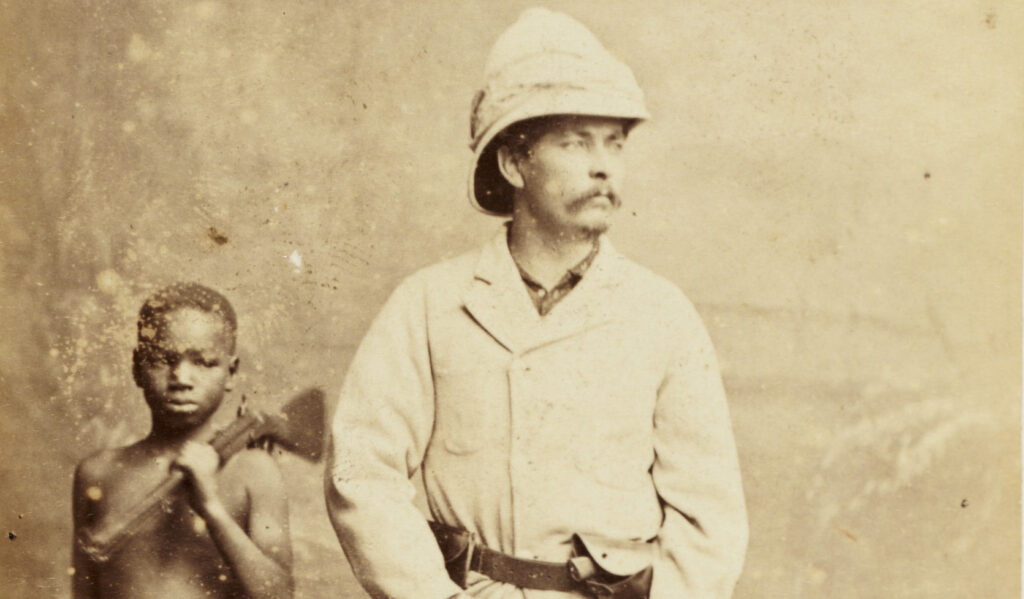

But, speaking of dead and buried, let’s note an odd trend that starts here. Stanley’s 1871-1872 Livingstone expedition boasted 190 men: porters, guards, cooks, interpreters, etc. But only three were white: Stanley and two British sailors. Both sailors died during the expedition. And though Stanley and Dr. Livingstone explored together for several months after meeting, Livingstone died soon after they parted ways. Since Stanley’s European and American audience didn’t care what the African members of the expedition had to say, this story of a lifetime concluded, conveniently, without any witnesses who could contradict Stanley’s account.

It wouldn’t be the last time. In 1874, Stanley began an expedition to circumnavigate the African great lakes. The expedition had 228 people, of whom four were white: Stanley, brothers and fishermen Frank and Edward Pocock, and hotel clerk Frederick Barker. Stanley had 3,000 applicants to join him, but he chose these three well-intentioned knuckleheads instead of men who were more seasoned and, perhaps, less expendable.

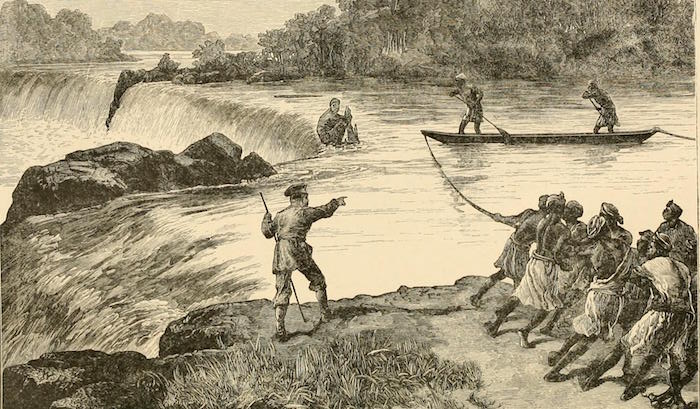

All went well at first. The expedition circumnavigated Lake Victoria. They diverted course to follow a huge river they thought might be the fabled headwaters of the Nile. (It turned out instead to be the headwaters of the Congo River.) But things turned ugly. Fred Barker died of fits, Edward Pocock of delirium. Frank Pockock drowned. Desertion, sickness, and raiding plagued the African contingent. Stanley almost starved. When the expedition finally straggled onto the shore of the Atlantic Ocean, there were only 114 survivors.

If you had to describe Stanley’s expeditions in a single word, it might be ‘violent’. He burned villages and towns, fired into crowds, and killed a lot of people he didn’t need to, often on pretext as flimsy as “quieting their mocking”. He meted out hundreds of lashings at a time to his partners and guards. Even by the standards of his time, Stanley was brutal. But remember his upbringing. In the workhouse, young John Rowlands surely learned to act hard and fight harder to stave off beatings and sexual assault. Small surprise that he never lost the habit. He doesn’t seem to have been any more racially-motivated than any of his less-bloody contemporaries (who were all pretty racially-motivated). The man just always shot first, even when he didn’t need to.

Stanley’s later expeditions were far larger and stocked with many more white explorers, officers, and adventurers than his first two. The most notable of these treks was the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition of 1886-1889 into South Sudan. The area was nominally run by the Egyptian Khedivate, the Ottoman Empire, and the British Crown (it’s complicated), but was functionally run by a German Jew popularly called Emin Pasha. Emin Pasha sent letters begging Europe for help putting down a Mahdist revolt, and the great states of Europe put together a relief expedition of soldiers and supplies commanded by Stanley. He would march overland from the Congo into South Sudan and bring Emin Pasha out alive. The accounts of the white survivors on this expedition offer us a valuable insight into Stanley’s methods.

Stanley’s first priority was glory. He split the force into two columns. The first, led by him, would march unencumbered by baggage to reach Emin Pasha as fast as possible. It wouldn’t be able to do anything once it got there, lacking the manpower or equipment to be a credible force, but Stanley would get some nice headlines out of it. The second column was supposed to follow along behind, but its commander quickly went mad. He dispatched officers on three-thousand-mile round-trips to send nonsensical telegrams. He whipped someone to death, decided he was being poisoned, and even bit somebody.

When Stanley’s lead column reached Emin Pasha, half of them were nearly dead of starvation and the rest were actually dead of starvation, as Stanley’s route took them straight through an unmapped rainforest at the request of the King of Belgium. By now, a few years had passed since Emin Pasha sent those letters, and he didn’t need the help anymore. Still, the arrival of hundreds of European soldiers with itchy trigger fingers and a commander who let them run wild stirred the Mahdist rebels up again. Emin Pasha reluctantly agreed to leave South Sudan with Stanley, who would accept no other outcome. If Stanley didn’t bring Emin Pasha with him, the newspapers might have called the expedition a failure!

Emin Pasha almost didn’t make it out of Africa. In weird echoes of Dr. Livingstone’s death, in the middle of a fancy ‘we’re-glad-you-made-it-out-OK’ reception in German-ruled Tanzania, Emin Pasha walked right out a second-story window. Apparently, he confused it for a balcony. He had to stay in the hospital for two months, but he eventually recovered.

Now, while I am floating a conspiracy theory about Henry Stanley killing witnesses to cover something up, it’s obviously without any real merit (and even less support!). Me pushing it is purely tongue-in-cheek. (Remember when conspiracy theories were fun and didn’t destabilize democracies?) With that caveat out of the way, what might Stanley have wanted to hide? The obvious answer is ‘lies’! A Frenchman passing through Uganda once caught Stanley in a baldface lie about how he converted the Ugandan emperor to Christianity. Who knows what other self-aggrandizing falsehoods he might have killed to protect? And while Stanley wrote sanguinely about the atrocities he meted out, maybe there were even worse ones of which even he was ashamed. Another possibility might be that Stanley had a bastard child in the Congo, something that would have hit the ex-bastard particularly hard. Yet another possibility is that Stanley’s second-in-command on the Emin Pasha expedition wasn’t his first white subordinate to go suddenly mad. Maybe something about Stanley just makes some men snap.

If you use Stanley’s story as a template for an event in your fictional campaign, it’s probably best if you make whatever he’s covering up either enormous or truly trivial. If you’re going to deploy a monster, lean into it! He’s either guilty of something heinous, or he’s willing to kill to cover up something irrelevant. Relatives of one of Stanley’s deceased white traveling companions might pay your PCs to go to the site of their loved one’s death and find out what really happened from the locals there. Other good sources might include the Wangara people of Zanzibar, whom Stanley relied on again and again as porters, and his two ex-fiancées and his wife, each of whom, successively, he was in frequent correspondence with while on expedition, via a long network of runners.

–

Source: King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild (1998).

I bought this book used. Shout out to the book’s previous owner, who underlined the phrase, “None of the white men on the expedition survived” and wrote in the margin, “Everybody who would be able to argue with Stanley’s tale does…”