Last month we looked at eleven bizarre scholarly NPCs from 1600s Britain, taken from a wonderful historical source: Aubrey’s Brief Lives. This week we return to the Lives for fourteen high-society NPCs, and – as before – we’re less interested in the real biographies of these people than in the gossip Aubrey reports about them. One NPC spent four years living among the Venezuelan natives of the Orinoco River. One escaped her father’s tower by climbing down a rope like Rapunzel (though without the hair). One was the first person to bribe the entire House of Commons. All are wild stories in their own right and are perfect to fictionalize and drop into your ongoing campaign! Fair warning; this post’s considerably more salacious than most of my stuff.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Sir John Denham (1615-1669) was the author of the first poem in English devoted to local description. He didn’t have a terribly high opinion of himself as a poet. When his frenemy the poet George Withers was in danger of execution, Denham went to the king and asked him not to hang Withers, for “while George Withers lived, [Denham] should not be the worst poet in England.”

Once, as a youthful prank, Denham and his friends took a pot of ink and attempted to blot out all the signs along a certain stretch of road. They were caught partway through, which meant they succeeded in disrupting traffic the next day, but they were also fined.

Denham married a beautiful young woman named Margaret Brooks, who was the object of the affections of the Duke of York. Aubrey denies that Brooks and the Duke ever slept together, but Denham was so jealous that he went briefly mad. The high point of his temporary condition was when he appeared before the king claiming to be the Holy Ghost.

Denham was ruined by gambling. He fell in with gamblers at a young age and his father chewed him out over it. To show his repentance, he wrote for his father an essay titled ‘Against Gaming and to Show the Vanities and Inconveniences of it’. But after his father died, Denham swiftly gambled away his inheritance.

An NPC based on Denham might be sympathetic to your players, especially if you introduce him by having the party bump into him mid-prank, inkpot in hand. Having him burst into court claiming earnestly to be some religious figure will likely provoke drama, especially with whoever also loves his wife. He could be manipulated by whoever holds his gambling debts, which could make him a great pawn in whatever scheme your villain is up to – a pawn the PCs might feel compelled to rescue.

Thomas Chaloner (1595-1661) was a member of Parliament and a staunch Parliamentarian during the Civil Wars. Chaloner’s signature appears on the document ordering the execution of King Charles I. Aubrey conflates this Thomas Chaloner with his father (1559-1615) who introduced alum manufacturing to England.

Aubrey tells us that when Chaloner was riding “in Yorkshire (where the alum-works now are) he took notice of the soil and foliage, and tasted the water, and found it to be like that where he had seen the alum-works in Germany. Whereupon he got a patent of the King (Charles I) for an alum-work (which was the first that ever was in England) which was worth to him two thousand pounds per annum, or better.” But Chaloner wasn’t a nobleman and someone at court felt a lowborn fellow like Chaloner shouldn’t be making that much money. So the courtier “prevailed upon the king that, notwithstanding the patent aforesaid, he granted half or more to another (a courtier) which was the reason that made Mr. Chaloner so interest himself for the Parliament-cause and, in revenge, to be one of the King’s judges.”

Chaloner liked to make up stories just to see if people would repeat them. He’d go into Parliament in the morning and tell some outrageous lie, then return around noon to see how it had spread. If other people had added to the story, like a game of telephone, he was all the more delighted.

After the restoration of the monarchy, King Charles II ordered Chaloner to hand over his castle. When word came to Chaloner, the Parliamentarian took poison. He vomited blood for three hours and then died. When the messenger entered to view the corpse, Chaloner’s face was so swollen his eyes could not be seen and his nose was no bigger than a wart.

An NPC based on this conflated Chaloner is great because he’s got a really good reason to be angry with the ruling power. If you need someone scheming in the background to assassinate your king, Chaloner is a great template! Plus, his habit of spreading lies is divisive. Some players find that sort of behavior silly and endearing, while others may view it as perverse mendacity. If your party disagrees about whether they like a given NPC, that may provoke interesting roleplay.

Sir John Suckling (1609-1642) was a poet and the inventor of the game of cribbage. He was a notorious gambler. “No shopkeeper would trust him for a sixpence, as today, for instance, he might be winning, be worth two hundred pounds, and the next day he might not be worth half so much, or perhaps sometimes be minus nihilo. … He played at cards rarely well, and did use to practice by himself abed, and there studied how the best way of managing the cards could be.” When he was doing badly, he’d dress up in fine clothes and return to the table, for he felt it improved his luck. Despite his gambling habits, Suckling was beloved of high society for his sparkling wit.

In 1637, Suckling played a truly tremendous prank on one of his friends. Suckling, the poet William Davenant (more on him later), and Jack Young were visiting the town of Bath. Young met a pretty girl and arranged a rendezvous with her that midnight. Little did he know Suckling and Davenant were listening in from the other side of a hedge. That night, the three were playing cards in a tavern when Young made a big show of being tired – so he could pretend to go to bed, sneak out the back, and have sex with the girl he’d met. Suckling pulled aside the landlady (tavernkeeper) and warned her that Young was insane: “[See] how he yawns? Now is his mad fit coming upon him.” When Young ‘went to bed’, Suckling had the landlady bar the door to his room from the outside so Young couldn’t leave. He warned her that Young would yell and swear and try to break down the door, so she must place the hostler, her strongest employee, at the door to restrain Young if he burst free. As the hour approached midnight, Young got up and tried the door. He knocked, then (understandably) bounced, stamped, cursed, and ultimately broke it down. “The hostler, a huge lusty fellow, fell upon him and held him and cried, ‘Good sir, take God in your mind, you shall not go out to destroy yourself!’” Suckling and Davenant sat in the next room, laughing until they cried.

Suckling once got into a dispute with Sir John Digby, maybe over a mistress or a card game. Digby was one of the best swordsmen of his day and Suckling decidedly wasn’t. Suckling and two or three friends ambushed Digby while he was entering a theater, but Digby drew steel and drove back Suckling’s party until they fled. This made Suckling doubly a coward: once for the ambush and again for running. Suddenly, Suckling found himself persona non grata in London high society. This continued until one Lady Moray invited Suckling to a party. Everyone there snubbed him and upbraided him, save Lady Moray who announced, “I am a merry wench and will never forsake an old friend in disgrace. So come sit down by me, Sir John.” This raised his spirits so much that his sparkling wit returned and no one found they could stay mad at him.

Eventually Suckling ran out of money. He went to France, found life little better there, and took poison. He was 33 years old.

An NPC based on Suckling might be a useful disruptive influence. Everyone likes him, but he’s always getting into trouble and causing trouble for others. If things are going too well for the PCs, Suckling can pop up to complicate their lives. NPCs like Suckling can be hard to run at the table; it’s tricky to play someone wittier or more charming than you are. Prepare a few witticisms in advance and lean heavily on the flattery.

Thomas Sutton (1532-1611) was a businessman. He got his start in coal, then augmented his fortune (or so Aubrey tells us) by wooing the young, buxom wife of an aged brewer. The brewer had a contract to sell beer to the navy and was very rich. When the brewer died, he left his fortune to his young wife who immediately married her paramour Sutton and passed her newfound wealth on to him.

Money begets money. No one in 1600s Britain got rich working for a wage, and little has changed since. By the time he was old, Sutton was one of the richest men in England. He had so many chests full of cash in his house that the floors groaned under their weight. One of his friends confided in Aubrey a fear that Sutton’s very home would collapse. Sutton had no children and no heirs to pass his great wealth to. “The earl of Dorset mightily courted him and presented him, hoping to have been his heir, and so did several other great persons.”

A NPC based on Sutton is a wealthy, heirless lady’s man. Several prominent NPCs are sucking up to him, trying to become his primary heir. They may enlist the PCs to help their cause or discredit their rivals. Sutton enjoys the attention. He hasn’t told anyone he’s leaving everything to charity.

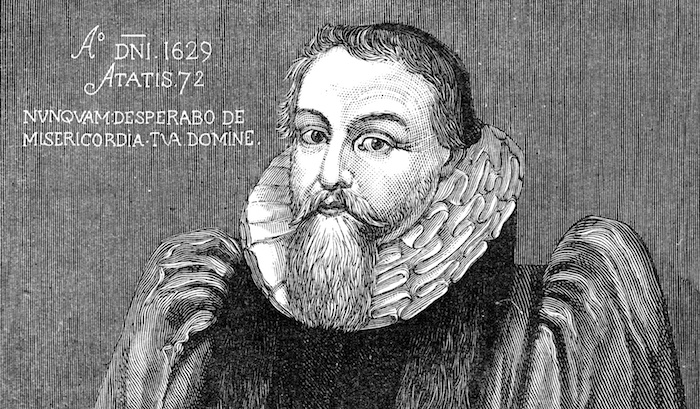

John Whitson (1557-1629), Alderman of the city of Bristol, has another salacious story of marriage. He was an apprenticed to a wealthy merchant with a beautiful wife. When the merchant died, his widow called Whitson “into the wine cellar and bade him broach the best butt (barrel) in the cellar for her; and truly he broached [the widow], who after married him.”

Sir William Davenant (1606-1668), a dramatist, based the character of beautiful Dalga in his epic poem Gondibert on a woman in Westminster who gave him a case of syphilis that cost him his nose.

Sir Henry Blount (1602-1682), teetotaler and friend of King Charles I, was the author of a weird bet. He overheard one Colonel Betridge, a handsome man, bragging about how much the ladies loved him. Blount bet Betridge that if they were to go together into a brothel, Blount with twenty shillings and Betrdge with only his handsome face, that the women there would prefer Blount’s money to Betridge’s charms. Blount won the bet, so… good for him, I guess?

The father of Elizabeth Broughton locked her in a tower in his manor because she had sex with a parish clerk. She escaped by lowering herself down on a rope. She traveled to London and supported herself quite well as a high-class prostitute. She was well enough known for someone to have composed a ditty about her:

From the watch at twelve o’clock

And from Bess Broughton’s buttoned smock

Deliver us O Lord

Thomas Stump (born 1616) was a captain in the Royalist army. At the age of 16, he was on a sea voyage that stopped in what is today Venezuela. He and four others went too far inland from the ship. The wind turned, the captain didn’t want to lose it, and he left without Stump and company. The native people of the Orinoco river seized the Englishmen and (according to Aubrey anyway) ate the three who had beards. The other two threw themselves in the river to drown, but Stump was too buoyant and survived. He then lived with the locals for four years until he could thumb a ride aboard a passing Portuguese ship. As a grown man back in England, Stump liked to tell wild stories of the marvelous and pleasant life he enjoyed along the Orinoco.

Richard Corbet (1582-1635) was a scholar of divinity. He liked to sing ballads in taverns and often did better than the actual bards working the taverns to earn their living.

Playwrights Francis Beaumont (1584-1616) and John Fletcher (1579-1625) lived in a polycule “together on the bankside, not far from the playhouse, both bachelors; lay together; had one wench in the house between them which they did so admire; the same clothes and cloak etc between them.”

Walter Rumsey (1584-1660), a lawyer, was so plagued with phlegm that he invented a stick of whalebone with a rag on it that he could shove down his throat and use to draw up the phlegm. He could touch the bottom of his stomach with it. “If troubled with the wind, it cures you immediately, with a blast as when a bottle is unstoppered.”

Edmund Waller (1606-1687) was the first man to bribe the entire House of Commons. He was a Royalist, and the Parliamentarians wanted him hanged for plotting to deliver London to the king. He was tried before the whole House of Commons. To save his neck, he sold his estate – very cheaply too, since he had to find a buyer immediately – and divided the profits among the members of Parliament.

Finally, they’re not high-society, but I couldn’t wrap up this Aubrey series without mentioning the Five Women-Barbers: “There was a married woman in Drury Lane that had clapt (i.e. given the pox to) a woman’s husband, a neighbor of hers. She complained of this to her neighbor gossips. So they all concluded on this revenge, viz. to get her and whip her and shave all the hair off her pudenda, which severities were executed and put into a ballad. ’Twas the first ballad I ever cared for the reading of. The burden of it was thus:

“Did you ever hear the like

Or ever heard the same

Of the five Women-Barbers

That lived in Drury Lane?”

About the source, Aubrey’s Brief Lives

John Aubrey (1626-1697) was an English country gentleman. He had the ambition to write a collection of biographies of the great Britons of his era: roughly the 1600s, though he included many men who died old in the early 1600s, and so we think of as being more Elizabethan in character. Aubrey compiled a great collection of salacious gossip – mostly obtained at drinking parties – but he never actually wrote his book. Instead, he left behind a collection of notes and letters full of the sorts of details that seldom make it into sober scholarship. The longer and more interesting contents of these papers have been often published under the title Aubrey’s Brief Lives.

A good example of the content of Aubrey’s Lives is this quote about Edward de Vere, which you may be familiar with: “This Earl of Oxford, making of his low obeisance to Queen Elizabeth, happened to let a fart, at which he was so abashed and ashamed that he went to travel for seven years. On his return, the Queen welcomed him home and said, ‘My lord, I had forgotten the fart.’”

It’s amazing seeing 17th century Britain – a wild period full of civil wars, a regicide, a theocratic dictatorship, the restoration of the monarchy, and so much gilt and ostentation – through the eyes of one particular human with all his idiosyncrasies. Newton may be found in Aubrey, but only as an idle mention in other people’s stories. Shakespeare is in Aubrey, but only his comedies are mentioned – and only A Midsummer Night’s Dream by name. Aubrey seems less interested in Shakespeare’s literary work than in his friendship with Ben Johnson. By contrast, Aubrey presents an endless parade of doctors of divinity, breathlessly describing their interchangeable virtues.

Women appear rarely, and usually only in reference to their beauty or sexual proclivities. A good example is the entry for Eleanor Radcliffe, the Countess of Sussex: “A great and sad example of the power of lust and slavery of it. She was as great a beauty as any in England, and had a good wit. After her lord’s death (he was jealous) she sends for one (formerly her footman) and makes him groom of the chamber. He had the pox and she knew it; a damnable Scot. He was not very handsome, but his body of an exquisite shape. His nostrils were stuffed and borne out with corks in which were quills to breathe through. About 1666 this countess died of the Pox.”