From 1723 to 1725, the French asylum at Charenton held a patient named Hu John, a Chinese Catholic. How Hu got to France and how he came to be committed is a remarkable story. Springing him is an even better adventure!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

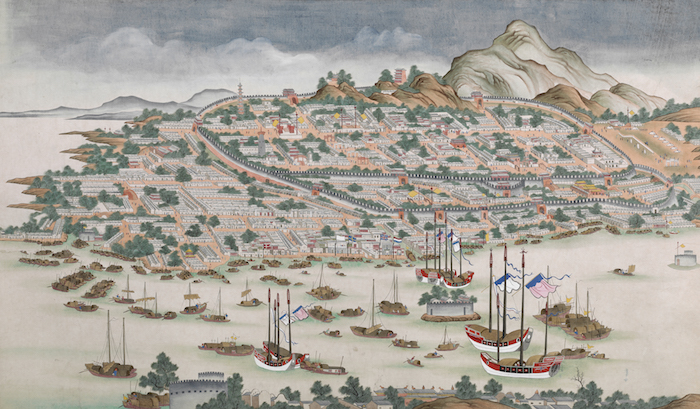

Hu was born around 1681 near Guangzhou, in southern China. He converted to Catholicism at age 19 and took ‘John’ as his baptismal name. By age 40, Hu John (family names come first in China) was a widower and his only child was almost grown. He had a job at the Jesuit mission in Guangzhou as the keeper of the gate. If someone approached the mission looking to talk to the priests, it was Hu’s job to gauge whether to admit them. He was literate but not educated. Except for his religion, he was an utterly unremarkable man. This would soon change.

Also at the mission was a French priest named Jean-François Foucquet. He’d spent decades in China. As a Jesuit (an order devoted to academic study and education as a means towards proselytization), he’d spent that time studying the great works of Chinese literature. Foucquet had become convinced that the Chinese classical canon was divinely inspired by the one true (Christian) god, but that the Chinese – lacking Jesus – were not able to properly understand their own literature. This idea was rather insulting to the Chinese and not particularly palatable to the Catholic Church, which frowned at viewing infidel texts as having godly merit. Foucquet had amassed a great library of classical works and commentaries and intended to bring it home to Europe and prove to the Church that Christians could glean divine knowledge from Chinese antiquity.

Foucquet wanted an assistant to help him with this work. Ideally, he’d love a scribe who could copy the books in his library so they’d not become irreplaceable when they reached Europe. The Jesuit mission employed several local Cantonese scribes. But Foucquet’s superiors disapproved of his goals and convinced the scribes to refuse to travel with him to Europe. With only 24 hours until Foucquet’s ship left, someone told him about Hu. There was no time to vet Hu, no time to determine whether he’d make as good a scribe as he made a gatekeeper. Hu had nothing keeping him in Guangzhou and cheerfully volunteered. He signed a contract promising him 20 ounces of silver a year for five years in exchange for regular copy work. Hu had visions of traveling to Rome to meet the Pope, then returning to Guangzhou to write a bestselling travelogue.

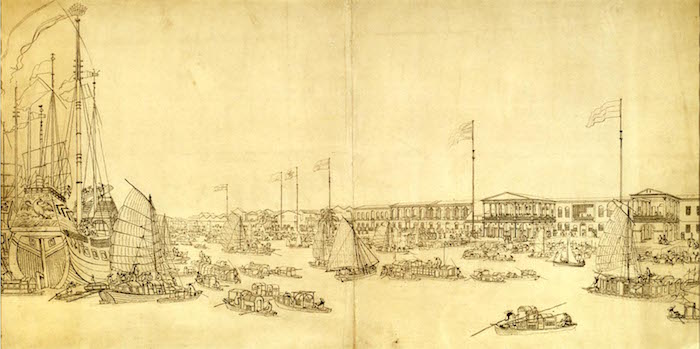

Things went badly almost immediately. The trip to Europe took months longer than it should have. The crew almost died of dehydration and scurvy. The ship fought a battle with a Portuguese patroller when both ships mistook the other for a pirate. Hu was seasick most of the trip (far, far longer than is normal). The only other person aboard who spoke Cantonese was Foucquet, but they didn’t dine together; Foucquet dined with the officers and Hu dined with the clerks and stewards and whatnot. There were cultural misunderstandings. Hu didn’t understand that he was only allotted so much food and couldn’t go into the galley to get more, and the only way his messmates could figure out to deter him was to beat him. But some of his behavior went beyond cultural differences. Hu refused to learn a word of French. He got into fights. He insisted he mediate a dispute between the ship and a harbormaster, even though neither side spoke Cantonese. And he had visions of angels that promised he’d convert the Emperor of China. Foucquet began to wonder if Hu was entirely sane.

When the ship reached France, Hu’s behavior grew more erratic. One may guess that between the isolation and the total lack of anything familiar, Hu was cracking. The pair slowly made their way through France while Foucquet (via letters) navigated the religious politics he’d embroiled himself in, fending off representatives of the Pope, the King of France, and the French Catholic Church. This left him little time to tend to Hu. In the months they spent crossing France stop-and-go (more stop than go), Hu performed a multitude of strange actions. Some were, again, cultural misunderstandings. Hu was demonstrating a remarkable refusal to adapt to local customs, but these actions at least made sense – though they were indistinguishable from madness to most Frenchmen:

- Kowtowing to crucifixes

- Leaping from the stagecoach to investigate every new thing, necessitating stops every five minutes

- Being livid that women attended mass along with men

- Rearranging the furniture in Church ceremonial rooms to fit Chinese conventions

- Still refusing to learn any French at all

Other actions were not so explicable:

- Stealing a horse

- Breaking down a locked door

- Making a drum and a flag that said (in Chinese) “women and men belong in separate spheres” and parading through town

- Disappearing from Paris and walking in the winter rain, unaccompanied, seventy miles to Orléans

- Standing on the steps of churches and giving full sermons in Cantonese to passers-by, drawing crowds and soon becoming a popular fixture of the Paris street scene

- Becoming convinced Foucquet had killed somebody. He later reported someone had told him that, but he couldn’t remember who – and who could it have been, since Hu didn’t speak French?

- Waving knives, getting into fights, and causing scenes everywhere he went

Since leaving Guangzhou, Hu had performed only a few hours of copying, the work he’d actually been hired to do.

If Hu had been French, Foucquet would simply have fired him. But that wasn’t an option. Hu was only in France because Foucquet had brought him here; Hu was Foucquet’s responsibility. And to his credit, Foucquet persisted in keeping and traveling with Hu for far longer than most of us would have. But eventually Foucquet received orders to travel to Rome with his library and Hu refused to go with him – despite Rome being his primary motivation for leaving Guangzhou. So Foucquet left him behind. When forced to choose between his priestly responsibility to his charge and his scholarly responsibility to his life’s work, he chose the latter.

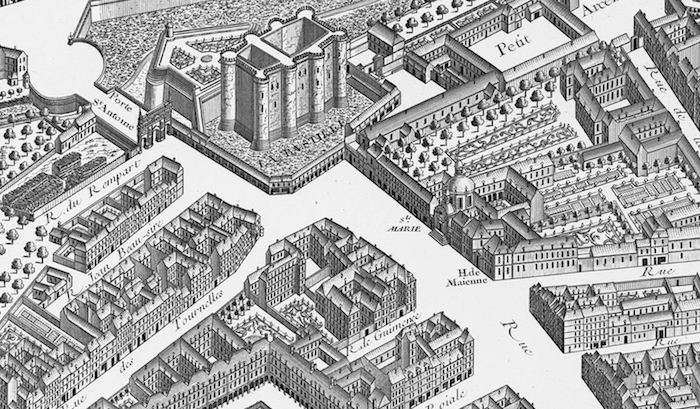

Hu was committed to an asylum. Foucquet and the nuncio (papal ambassador) to France asked for help from the head of the Guet or Archers of the Watch, a sort of semi-professional proto-police force that guarded Paris. The Lieutenant of the Guet reported directly to young King Louis XV. The Lieutenant, at the request of the nuncio, worked with the Secretary of State (the King’s head minister) to draft an order in the King’s name involuntarily committing Hu without a trial. Between the nuncio, the Lieutenant of the Guet, the Secretary of State, and King Louis, Hu had suddenly gained the attention of four of the most powerful men in and around Paris.

Hu’s asylum at Charenton was an odd place. It was run by a Catholic order devoted to helping the poor and unfortunate. Hu had a small cell with a window. He had a latrine that flowed into a bucket outside. Sometimes he was let out into the courtyard, where he could lie under the sky. By the standards of the day, Charenton was a remarkably humanitarian institution. By our standards, it looks a lot like solitary confinement – plus the walls were inadvertently built such that no breeze could penetrate Hu’s part of the compound and it always stank of excrement. Other parts of the facility were much nicer, with tapestries, fine food, and even a billiards room. This section served as an old folks’ home for wealthy invalids. (There was also a hospital.) Folks paid to send their family members to Charenton, which in turn funded the order’s other charitable activities. Hu’s order of commitment included a promise of payment, but no money ever arrived from Versailles or Rome.

Hu’s condition at Charenton seems to have been one of benign neglect; there’s no evidence he was abused or mistreated, but neither did anyone pay any attention to him, for he had no family to advocate for his good treatment nor could he advocate (in French) on his own. The Lieutenant of the Guet forbade that Hu receive visitors. All we know of what Hu got up to during this time is that he was once given a wool blanket and tore it to shreds.

Hu spent two and a half years in the asylum. It wasn’t clear whether he was getting better. Every so often, someone from the Church would come by to check on him. Some reported he was sane. Some denied it. None spoke Cantonese. The asylum wanted him gone, since he wasn’t generating revenue. The powerful men who’d had Hu committed insisted he stay.

Then Hu caught a lucky break. The nuncio became aware of a Vietnamese man living in Paris. He and the Augustinian who’d converted him got stuck in Guangzhou for a year waiting for a ship while traveling from Vietnam to Europe. While there, the Vietnamese convert had learned Cantonese. In France, he’d learned French. The nuncio made a visit to Hu and took the Vietnamese convert along as a translator. Hu complained to them about his imprisonment and that he hadn’t been paid the twenty ounces of silver a year he was promised. When asked about the blanket, he explained he shredded it simply because he could. It was nice to feel agency for a moment. The nuncio suspected Hu might be sane. A newly-arrived (Cantonese-speaking) priest from the Jesuit mission in Guangzhou – one of Foucquet’s old intellectual enemies – also visited Hu and agreed. Whether he was mad in the past or not, Hu now seemed sane.

Then another lucky break: the Secretary of State died and the Lieutenant of the Guet changed jobs. Their replacements saw the situation with fresh eyes. They also saw the bill their predecessors had never paid. With the nuncio, Secretary of State, and Lieutenant of the Guet all on board, they issued a new order releasing Hu from Charenton. The new Lieutenant put Hu up in a comfortable suite of rooms, chartered him passage to China in a few months, and arranged a tutor to teach Hu some French.

Once freed, Hu immediately returned to his former behavior. He caused so many scenes in his apartments that the Lieutenant had him transferred to the home of the nuncio. He behaved the same there. He refused to participate in his French lessons. When the time came to put Hu on a coach to the port, he fought the men trying to get him in the coach and had to be bodily forced in – even though one of those men was the Cantonese-speaking Jesuit from earlier, so Hu was told what was going on. Upon his return to Guangzhou, Hu demanded his back pay from the Jesuit mission – pay for work he never completed. They gave him a little money to get rid of him. Hu spent the money on fine clothes. His grown son, ashamed, soon fled to a Christian mission in Macau to get away from his father.

At your table, there are a lot of ways you can turn an NPC based on Hu into an adventure hook. The Hu-analogue you put in your fictional setting might have made a full recovery, or even have never been mad in the first place. You can certainly make all of the ‘symptoms’ your Hu was committed for be cultural misunderstandings. Or you can say that Hu really did go mad, but that he’s recovered since. If your Hu-analogue is now sane, there’s a clear plot hook: spring him from the asylum!

You could certainly treat sneaking Hu out of the asylum as a heist. I’ve talked before about my preferred ways of running heists, but if you do want to run this as a traditional, Shadowrun-style heist with lots of reconnaissance and planning, this would be a good setting for it. I’ll confess to not yet having read Blades in the Dark (let alone played it), but from what little I know of it, heisting a possible madman from an 18th-century asylum seems like a great fit.

Or your party might want to attempt a political solution to freeing your Hu-analogue. This is what happened in real life. The coincident arrival of a Chinese speaker and a sympathetic new guard captain caused Hu to be freed without consequential involvement from Rome. Your PCs might be those two new arrivals (or something like them), change the information available to the powers-that-be, and get your Hu-analogue freed.

On the other hand, you might want to cleave more closely to real history and have your Hu-analogue still be insane or be questionably sane. In that case, it’s less likely your players will want to spring him out of the goodness of their hearts. They might be hired by the embassy of the nation your madman is from. Or maybe the NPC who brought Hu all this way has become politically powerful and Hu is now a liability to her and needs to be brought out of the country in a way that can’t be tied back to her. Maybe the PCs are even hired in Hu’s homeland to find him and bring him back! In any case, a heist and politics are probably still your two chief avenues of escape. Make sure you have your Hu-analogue create a scene at the least convenient moment to confound your party’s best-laid plans!

If you know a few sessions in advance that you want to do a Hu plot, you might even have your PCs encounter him on the street: an NPC from so far away he might be unique in this city, giving sermons to a delighted crowd in a language no one understands. Then when the PCs go to free your Hu-analogue, you can do a callback to when they met him before.

Check out Shanty Hunters, my RPG about collecting magical sea shanties in the year 1880!

Source: The Question of Hu by Jonathan D. Spence (1988). I simply must quote the last paragraph of the preface, which is breathtaking:

“Ultimately, however, it is on Foucquet that we have to depend for our detailed knowledge of Hu. … Foucquet did not attempt to prove his own innocence by erasing the past from the record. Instead, he carefully kept and filed away every memo and letter that came his way, even if the material did not show him in a pleasant light. He copied and recopied many such items, convinced that the record in its totality would vindicate his views of his own rightness. I don’t happen to think Foucquet was right in the way he treated Hu, but I am only able to make that judgement because he lets me. Thus even if I believe I have confronted him successfully Foucquet remains, in a way, the victor.”