The U.S. state of Missouri is full of caves. In the 1800s and early 1900s, Missourians put their caves to all kinds of uses. This human activity in caves is really useful when designing your own natural dungeons. Stick the interesting, gameable things Missourians did in their caves into your dungeons as hazards, obstacles, scenery, treasure, and cool NPCs!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

We start with a colorful example: a secret anatomy lab and horror-movie-esque mausoleum. In the late 1840s, the medical professor Dr. Joseph Nash McDowell bought a cave outside Hannibal, Missouri to use as an anatomy lab. Dissecting cadavers for medical education and experimentation was, though necessary, popularly considered abhorrent, and McDowell needed some out-of-the-way place he and his students could work in peace. Many of the corpses he dissected in his cave laboratory were stolen from cemeteries by paid “restrictionists,” and some were even the corpses of McDowell’s own children, dead from natural causes. McDowell installed a stout door on the cave mouth to keep out the uninitiated, but he didn’t know the cave had other entrances back in the maze of tunnels.

Teenagers sometimes crept down into McDowell’s cave to gawk at the horrors within. One teenager was a young Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) who later wrote a sensationalized version of McDowell’s story. McDowell’s weirdest activity in the cave was interring one of his dead daughters there in a copper casket filled with alcohol and suspended from the ceiling. Twain claims kids would sometimes sneak in and pull her out of the alcohol to have a look, but this seems inconsistent with other descriptions. Eventually, folks got concerned enough about the weird things teenagers claimed to have seen in the cave that a mob broke down the door. McDowell was forced to bury his daughter conventionally and stop using his cave for creepy mad science stuff. At your table, rumors of weird goings-on and a teenage guide leading them to a hidden entrance could be the impetus for characters to venture into a cave system full of weird human uses.

A more conventional—but dangerous—use for caves is guano mining. Gentry Cave, outside Springfield, Missouri, was home to gray bats who, over thousands of years, left enough poop on the floor of the cave to build deposits five feet deep. In the 1930s, C.L. Weekly mined these dry deposits and sold them as fertilizer. Old bat guano was historically mined as a source for all sorts of nitrogen-rich chemicals in the centuries before we got good at synthesizing them, including the nitrates needed to make gunpowder and TNT. Weekly and his two employees trekked into the cave with buckets and shovels, dug out the deposits, and brought them back to the cave mouth to spread out and dry further. Then they sifted out any rocks with wire screens, bagged the guano, and trekked it into town to put on a train. Guano mining can be dangerous. Depending on local conditions (especially how fresh the guano is—how many centuries it’s had to cure on the cave floor), guano dust can be explosive. Fresh, copious guano emits ammonia vapors that can knock out the unwary. And fungus often grows in the deposits, leaving toxic spores waiting to be stirred up. At your table, in addition to encountering guano miners (who might want to keep their mother lode a secret), the party might find the buckets, spades, and skeletons of miners who died mid-excavation, felled by the hazards that lie just beyond.

Image credit: Jacek Halicki. Released under a CC BY-SA 3.0 PL license.

Also mineable are a cave’s beautiful stone features. Flowstone, the stuff from which curtain walls, stalagmites, etc. are made, can be torn out and reworked into “cave onyx,” a kind of marble. At the turn of the 1900s, four men from St. Louis formed the Onondaga Mining Company to mine cave onyx in the Onondaga Cave outside Leasburg, Missouri, and sell it for the buildings at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. The venture was a bust, as were almost all cave onyx mines in Missouri, so the miners pivoted. They turned their mine into a show cave and sold tickets at the World’s Fair. Everything went swimmingly until the 1940s, when it was revealed that much of the underground tour occurred below land not owned by the tour company. The neighbors wanted a piece of the action and sued to make the Onondaga Cave people quit trespassing beneath their land. Then they opened up a rival tour company, Missouri Caverns, to show the part of the cave they owned. Fences went up underground to keep tourists from crossing the property line. The result was a bitter feud and competition for the same tourists. The feud didn’t end until all parties were dead and one operation leased both caves (which again, were the same cave, just artificially split by a property line). At your table, I love the idea of exploring a natural cave and unexpectedly coming across a fence blocking a passage. Long deposition of flowstone has locked the fence in place, like a tree growing around an injury, making it tough to remove without tools. There’s something cool on the other side of the fence; removing the fence is an obvious shortcut to it. But doing so will be noisy and might attract unwanted attention. Is it worth it?

(Separately, I’ve written a whole post about different flowstone features you can find in a cave and how to use it as combat terrain. It’s hidden behind my $2/month paywall for old posts.)

Image Credit: Hattiecb. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

The transition from mine to show cave is a great example of layering history onto your dungeons, a classic technique for making them seem real and lived-in—and for providing useful information that the PCs might use to their advantage. An interesting example of a cave with layered history is Knox Cave outside Springfield, Missouri. A nightclub operated there, lit with electric lamps, until 1924, when the Springfield chapter of the Ku Klux Klan bought it. This was quite the reversal for Knox Cave. At the time, the Klan wasn’t just racist, jingoist, and antisemitic, it was also strongly anti-alcohol. The Klan used the cave as their temple, carrying out their made-up sacred rituals to engender Masonic-style solidarity. In 1930, the Klan couldn’t make their mortgage payments on the cave and lost it. Knox Cave re-opened as a show cave under the name Temple Cave, playing on the mystical associations of the Klan, which was, at the time, powerful and popular among many white Protestants. In the 1960s, the cave (then as now billed as Fantastic Caverns) joined a move among Missouri show caves to get itself declared a fallout shelter. Everyone who visited Fantastic Caverns got a ticket promising them re-entry in case of nuclear armageddon. The government was still stashing civil defense supplies, food, and water in Missouri show caves as late as 1969. At your table, PCs exploring a now-abandoned cave based on Fantastic Caverns/Temple Cave/Knox Cave might find tucked away in little-visited passageways unspoiled supplies from the fallout shelter era, emergency lamps from the show cave, liquor from the nightclub (spoiled but sought after by collectors), and discarded evil artifacts from the rituals of your fictional analogue for the Klan.

Image Credit: Matt Howry. Released under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Onto any of this, you can layer treasure hunters (read: rival bands of adventurers). No treasure hoards have ever been found in any Missouri cave, but legends abound of Civil War loot and Spanish gold hidden way back in wild caves. Explorers searching for buried treasure have caused considerable damage, since they often used pickaxes and dynamite to open up passages and knock down walls. An abandoned treasure search may be indistinguishable from a wildcat mine: wheelbarrows, platforms, shoring, and blasting cord just lying around underground. Treasure-hunting reached its peak in the 1930s. The Great Depression left a shortage of good jobs, and the government was building dams in the Ozark Mountains whose reservoirs (like Table Rock Lake and Lake of the Ozarks) would flood caves and destroy cairns and marked trees supposedly left behind by treasure-hiders to help them find their loot again someday. For many unemployed Missourians with time on their hands, it was now or never to recover those lost hoards.

Another easy detail to add onto any natural cave is an outlaw or gang. It seems like every cave in Missouri was at some point the hideout of Jesse James’ gang or Confederate partisans. A less-famous outlaw was Peter Renfro. In 1888, he killed constable Charles Dorris at a picnic in Summerville, Missouri, then fled to a cave hideout. The only entrance to the cave the authorities could find was down a cliff face, approachable only from above. This route was so naturally well-fortified that authorities decided not to chance it. Even if the cave had other exits, and even if Renfro had friends bringing him food, he wouldn’t stay cooped up forever. The gamble worked; Renfro was arrested outside his cave a year later. A week before he was due to hang, he escaped jail and holed up in a different cave, where he evaded capture until 1898. Again, he was safe only as long as he was actually in the cave. His arrest happened in a bar. At your table, if the PCs bump into an outlaw inside a cave network, she could make a fantastic guide—as long as the PCs think they can trust her. For the outlaw, the PCs are a fabulous distraction, plus a source of outside news and fresh vegetables—but they also might reveal her location to the authorities. Will she get what she needs out of them, then guide them into a bottomless crevasse?

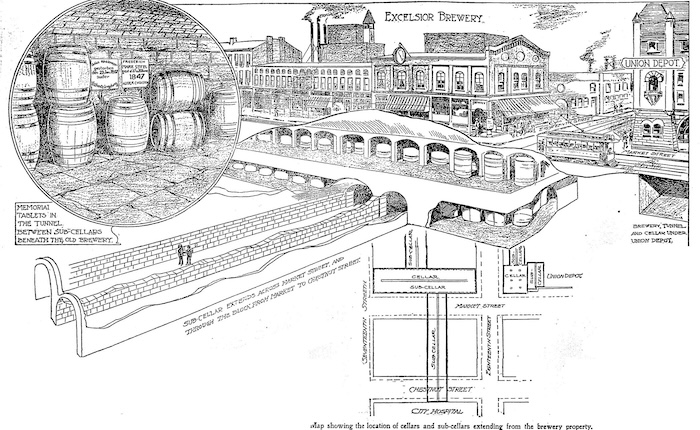

We close with the human cave feature St. Louis readers have been waiting for: breweries! A wave of German immigration to Missouri from the 1830s onwards brought with it plenty of brewers. Temperature is important to brewing. It affects the metabolic processes of the yeast. If you’re not brewing in an environment with a consistent temperature, batches of theoretically-identical beer can taste quite different, and an inconsistent product is bad for your brand. Caves are the same chilly temperature year-round, a temperature ideal for brewing many German-style beers. The St. Louis riverfront is full of caves, which is where these brewers set up their operations. Plus, in an era before refrigeration, the chilly caves made great warehouses for finished beer. Brewers even modified the caves to make them colder by expanding cave passages for better flow of air from underground and installing ice storage chambers. Many of the caves under St. Louis are interconnected, though tunnels may have filled with clay, gravel, and silt. Thus, nearby breweries often shared the same cave system without knowing it until they dug out a filled-in tunnel and found themselves in their neighbor’s brewery.

Make sure you don’t miss a blog post by subscribing to my no-frills, every-other-week mailing list! I also have a signup that’s only for big product releases!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need! Posts older than a year are behind a very cheap paywall – only $2/month!

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp. On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Blue Sky, I’m @moltensulfur.bsky.social.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on social media, or maybe emailing it to a GM friend of yours. The social media infrastructure that creators relied upon to grow their audiences is collapsing. You sharing my stuff helps me stay relevant and ultimately helps me get paid for my time.

Check out Shanty Hunters, my award-winning TTRPG about collecting magical sea shanties in the year 1880, then singing them at the table with your friends. The lyrics of the shanties come to life and cause problems for you and for the crew of the ship you sail aboard. It’s up to you to find clues in the song and put things right!

Source: Missouri Caves in History and Legend by H. Dwight Weaver (2008)