We’ve talked twice before about Ibn Battuta, the medieval Moroccan traveler. This time, we’re going to talk about his adventures in the Maldives, a paradisiacal tropical archipelago south of India. In the Maldives, Ibn Battuta got pressed into service as an Islamic judge, let his bad attitude get him into political trouble, and plotted a coup against the local sultana. If you fictionalize Ibn Battuta and stick him in your campaign setting, this makes a great RPG adventure hook – whether the PCs work with him or against him!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Joel Dalenberg. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Joel, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Image credit: Weetjesman. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Ibn Battuta had an interesting profession. Islam provided a shared culture across much of Asia and Africa in the Middle Ages. It didn’t matter what language your people spoke; if you were educated, you also spoke classical Arabic so you could read the Quran. Islamic scholars were valued everywhere. Ibn Battuta found that leaders would give him gifts in exchange for his educated counsel in matters of rulership and jurisprudence. These presents – money, provisions, mounts, slaves, and robes of state – funded further travel to further rulers. And the more he met, the more he could tell kings and sultans ‘this is how this ruler handled a similar problem to what you’re facing’. He effectively became a management consultant as a way to pay for his travel hobby. By the time he reached Delhi, Ibn Battuta had grown so wealthy that his baggage train had forty people and a thousand horses. There he found temporary work as a qadi: an Islamic judge.

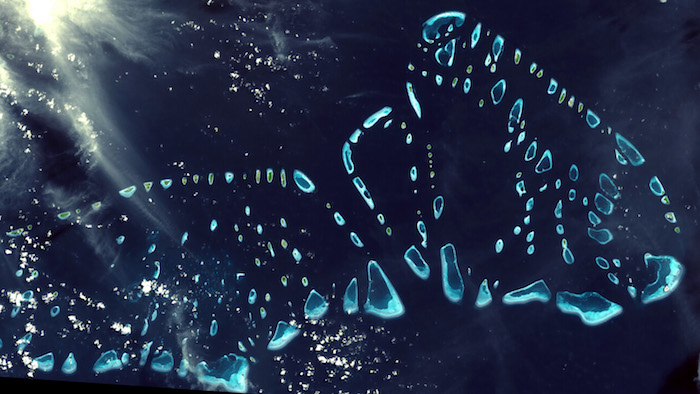

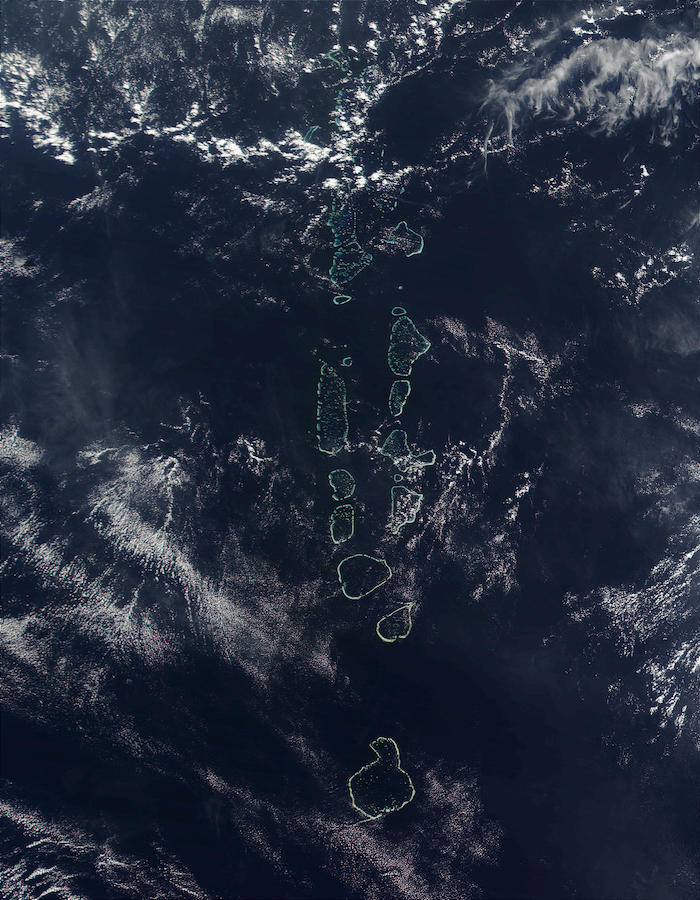

From India, Ibn Battuta reached the Maldives, a string of some twenty-odd atolls: circular rings of white sand atop old dead coral. Each atoll is then further subdivided into many little islands. While the archipelago’s small population had been Buddhist for centuries, by the time Ibn Battuta arrived in the 1340s, they’d converted to Islam. Ibn Battuta recounts a strange tale of the islands’ conversion. The Maldives were plagued by an evil djinn that visited every month. And every month the people had to sacrifice a maiden to get the djinn to leave. A hafiz (someone who has memorized the Quran) named Abu’l Barakat al-Barbari was shipwrecked in the Maldives. He waited for the djinn and defeated it by reciting scripture at it. Everyone was so impressed that they converted. The djinn still comes back every month in the form of a great ship full of lamps and torches, but as long as the islands remain Muslim it doesn’t land.

The Maldivians’ faith served as their armor. Pirates did not prey upon the Maldives for they’d learned that all who seize anything from them meet terrible misfortune. This was despite the fact that the Maldives’ chief export – cowrie shells – were literally money. Folks harvested the live mollusks, piled them in pits so the flesh could rot away, and then sold the clean shells to traders at a rate of a half a million cowries to the dinar. Traders brought the cowries to Bengal, Yemen, and North Africa were they were used as currency; Ibn Battuta reports seeing them used in Mali at an exchange rate of one thousand to the dinar. Yet despite the wealth of the Maldives, Ibn Battuta tells us the people there were unused to violence. When he ordered a thief’s hand cut off, some in the room fainted.

Our traveler has much to say about the women of the Maldives. He reports a custom where local women marry travelers, remain married (and sexually available) for the duration of their stay, then divorce them when they leave. We are assured that Maldivian women never leave the archipelago. Ibn Battuta himself married four women this way and took several concubines. He praises their prodigious sexual appetites, yet complains of their immodesty in public. The fashion was to go topless, which Ibn Battuta found un-Islamic. His efforts to rectify this practice yielded mostly laughter. Finally, Ibn Battuta was suspicious of his wives’ eating habits. It was the tradition, he tells us, that women would not eat in front of men and that their husbands would not even know what they ate. No ruse of his was ever able to pierce this veil of secrecy.

When Ibn Battuta reached the Maldives, his host informed him that if the ruler found out he was here, he’d surely be detained and pressed into service, for the Maldives at the time had no qadi (Islamic judge). Ibn Battuta tried to keep his identity secret, for he planned to travel onwards towards China. But some other travelers knew him and ratted him out. He tried to flee, paying for passage by selling some gifts the ruler gave him. But the powers that be heard about Ibn Battuta’s intentions and trapped him by asking for the gifts back before he left. They were sold, so he couldn’t, and he stayed. He was first pressured into marrying into the into the royal family, then into becoming the Maldives’ qadi.

The royal family was a little complicated. We’re going to introduce three persons of interest who will matter a great deal later in this story. First is the ruler, the sultana (queen) Khadija. Her father had previously been the sultan. When he died, the throne passed to her younger brother, who became sultan. But her brother was a child and required a regent. So another man, Abdullah Muhammad of Hadhramaut, married the minor sultan’s mother and became the regent. The younger brother chafed at the regency and when he came of age, he exiled Abdullah from the Maldives. But the younger brother slept with the wives of too many of his courtiers and they assassinated him. With no remaining male heirs, Khadija ascended to the throne. She married a man named Jamal al-Din, who became her vizier. He was powerful and handled many of her affairs of state, though Khadija remained the unquestioned ruler. With the old sultan (Khadija’s younger brother) dead, Abdullah returned from exile and rejoined court life. Ibn Battuta was bound by marriage to two of these people: one of his four Maldivian wives was the mother of Khadija’s half-sister, one had been married to Khadija’s younger brother, one was Abdullah’s stepdaughter, and his fourth and favorite had previously been married to Abdullah’s son.

Ibn Battuta soon got into political trouble. Abdullah, the former regent, didn’t care for the Moroccan traveler. It’s not clear whether the brash Ibn Battuta did something to offend Abdullah or if this was a natural case of some people just not getting along. Soon someone brought a case against Abdullah – a case that Ibn Battuta, as qadi, had to rule on. The plaintiffs were wards of Abdullah. Their late father had placed their property in the hands of Abdullah until they came of age. Now that they were grown, Abdullah declined to release the property. Ibn Battuta loved feeling important and seems to have resented Abdullah’s coldness towards him. So he summoned Abdullah to his court the same way he’d summon any other accused criminal, with no regard for Abdullah’s station. Abdullah, naturally, refused. So Ibn Battuta placed him under sanction: he forbade anyone to render honor to Abdullah as a member of the royal family. Ibn Battuta reports the royal family grudgingly obeyed this decree, but that it strained his relations with them.

Then came another case. An enslaved man owned by Jamal al-Din, the sultana’s husband, was caught sleeping with one of Jamal’s concubines. The next day, Ibn Battuta attended court (as was his place as qadi) but declined to mention anything about the case. This was uncharacteristic; the Moroccan loved to opine even about cases where his advice was not sought. Later, a minister of Jamal’s asked Ibn Battuta in the traveler’s home for his opinion on the case. Ibn Battuta, seeing an opportunity to throw his weight around, declared the matter too important to discuss there. It must be discussed at court, where he’d just refused to discuss it. The next day at court he ordered both the concubine and the slave beaten, the concubine released, and the slave imprisoned for further beatings. From context, we may gather that the enslaved man, while unfree, might have nonetheless been someone of consequence at court. Jamal tried to intercede on the slave’s behalf, but Ibn Battuta ordered the prisoner beaten all the more harshly, then had him paraded around the island. Jamal, furious, summoned the qadi, who addressed him insubordinately with a simple as-salamu alaykum and resigned. This huffy behavior did little to endear him to anyone.

Ibn Battuta prepared to leave the Maldives. This scared the royal family, who feared he might return to Delhi to foment trouble against them. He sold his gifts to repay his debts. He planned to take with him two of the four women he’d married in the Maldives. The other two he divorced, including one who was pregnant.

Ibn Battuta was so mad at his perceived mistreatment that he tried to plot a coup. He formed a compact with two ministers: the commander of the army and the commander of the navy. (As an aside, the latter had a daughter Ibn Battuta had planned to marry, but she refused him.) The Moroccan would sail for Madurai, in southern India. The sultan there was the husband of the sister of one of Ibn Battuta’s remaining wives. He’d convince the sultan to give him troops. He’d then return to the Maldives and hoist white flags upon his ships. This was the signal for the Maldivian military to rise up. Together, they’d conquer the islands for Madurai. The sultan of Madurai would surely appoint Ibn Battuta to rule the Maldives on his behalf, and the current commanders of the army and navy would presumably receive promotions. (Not least because Ibn Battuta didn’t even speak the language of the people he was plotting to rule.)

Ultimately, nothing came of it. Ibn Battuta divorced one of his two remaining wives because she got sick and he didn’t want to deal with her. He sailed not for Madurai but for Ceylon, so we never even find out if the sultan of Madurai would have agreed to participate in this plot. Jamal soon forced Khadija from the throne. Khadija killed him and regained her throne, then married Abdullah, who did the same. So she killed Abdullah and took the throne for the third time. The Ibn Battuta business receded to a weird little footnote in her reign.

At your table, Ibn Battuta makes a terrific NPC. He’s a powerful, influential traveler who pops up in places, expects to be treated a certain way, and has a good chance of getting it. He’s educated, decisive, and incredibly knowledgeable, but he’s also petty, brash, and an absolute dog with women. Even if you don’t do anything with him, having a fictional NPC based on Ibn Battuta show up in the same town as your PCs is a great complication that will surely make messier and more difficult anything the party attempts. There’s even a memorable way the PCs can get into his good graces: help him figure out what (if anything) his wives are eating. This cunning scholar cannot for the life of him trick his wives into revealing it. He’s tried visiting unannounced, peeping through the windows, and even dressing up as a woman, but none of it has worked.

If the PCs get wind that your fictional Ibn Battuta-analogue is plotting a coup, they’ll have to figure out which side they’re on. Do they betray him to the legitimate authorities, even knowing he has friends at courts around the world? Do they ask to join his compact, hoping to be rewarded when the revolution comes? If they do neither and stay out of it, let the winner of this brewing dispute learn later that the party could have helped them and chose not to. In any of these three cases, adventure should arise naturally from those decisions, hopefully in a way that can be totally reactive on the GM’s part, and thus require minimal prepwork.

Last weekend, I had the opportunity to play a one-shot of Lancer, the much-lauded 2020 mech combat RPG. I was really impressed! The setting provided a unique take on the trope of a small mercenary company piloting giant stompy robots: the part of the galaxy near Earth is a post-scarcity utopia, but space farther out is a lot rougher. That’s where your missions tend to occur. Though the utopian government is distant and sometimes toothless, its existence provides a ‘good guy’ side that’s really refreshing.

Combat was a lot of fun. All our mechs played very differently; it mattered whether you had an anti-material rifle and jump jets or a big machine gun and walky feet. Every turn, I felt like I had interesting choices to make, but not so many options that I became paralyzed. The rules for what you can and can’t do are elegant and deliver a fun gameplay experience while also making sense in the fiction. Once we got the hang of the rules, combats felt speedy and tense. And the mech-building mechanic has a cool system that eases you into mech design and lets you spend a few sessions getting a feel for things before giving you access the staggering plethora of chassis, guns, and add-ons.

Finally, I was really impressed by the designers’ courage in including almost no rules for stuff other than mech combat. Sure, we were running around talking to people and solving mysteries, but all that stuff was basically just flipping a coin to see if we succeeded. The paucity of non-combat rules clearly conveyed the designers’ intent: this is a game about piloting giant stompy robots to shoot other giant stompy robots. All other stuff is secondary, and the designers trust you to handle it on your own as it comes up.

Props to the Lancer designers! They did a good job, and I had a lot of fun.

Sources:

The Travels of Ibn Battuta, Volume IV, translated by H.A.R. Gibb and C.F. Beckingham (1994)

When Asia Was the World by Stewart Gordon (2008)