The existence of police is something most developed societies take for granted. Police are as natural a part of our political order as laws, juries, and elections, right? Yet unlike those three, police (as we would recognize them) are a fairly recent development. In the next two weeks on the blog, we’re going to look at two really interesting cases of early police work in France from about two hundred years ago. One of the things that makes these cases so gameable is how clear it is that the parties involved are just inventing the rules of police work as they go along. You always have a lot of latitude to change things up when you’re adapting something from history to your fictional campaign, but these cases are even freer than usual. We’re going to start this week with the 1816-1820 case of the She-Wolf, a septuagenarian bandit leader who tangled with France’s equally colorful ‘first detective’!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Joel Dalenberg. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Joel, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

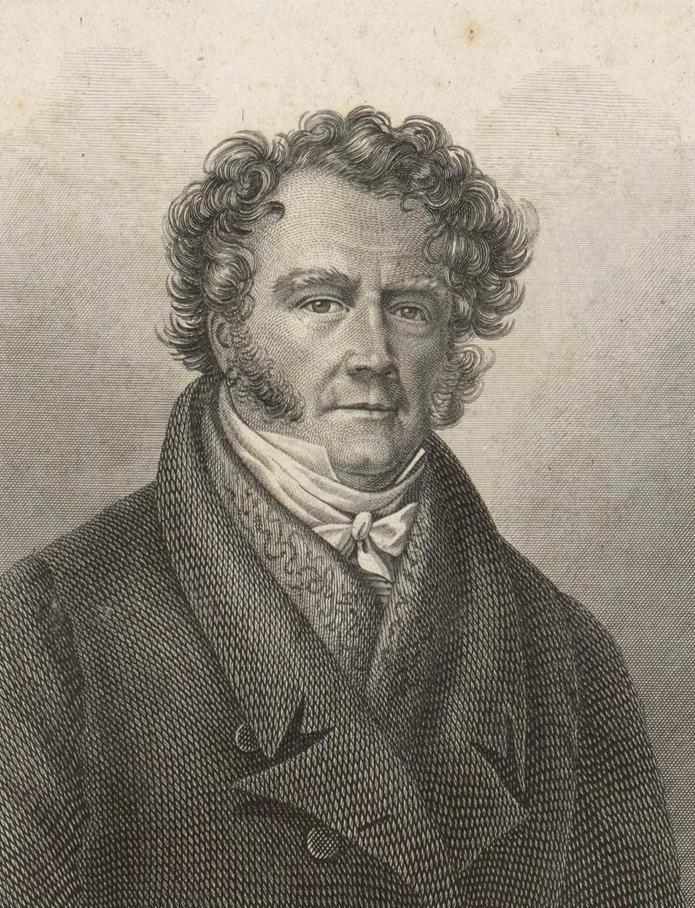

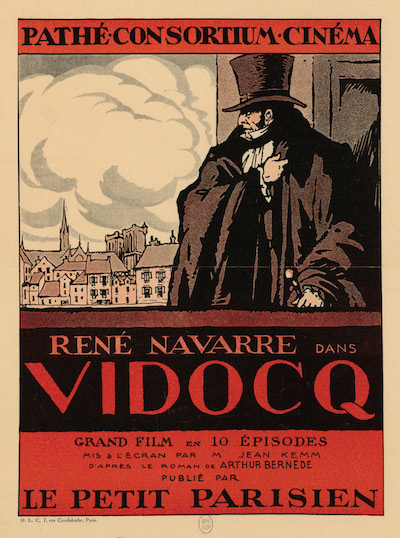

We first turn our attention to the case’s controversial lead detective, Eugène-François Vidocq. Vidocq grew up rough. He was fortunate enough to be born into a lower-middle-class family, but spent his youth stealing, drinking, starting fights, and being a dirtbag. His father disowned him and he took to traveling. He was a burglar, a card-sharp, a fence, a fraudster, and a professional accomplice – always happy to lend a hand in whatever scheme he heard about, as long as there was a little money in it. Through the French Wars of Revolution, he managed to stay (mostly) one step ahead of local police by enlisting in whatever unit was desperate enough for recruits not to ask questions, then deserting as soon as he could. He was charming, arrogant, an excellent fencer, and an accomplished womanizer.

Vidocq was eventually nabbed for forgery. He insisted he wasn’t a participant in the crime, that he simply happened to be in the room where the forgery happened, but no one bought it. He was already in prison for something minor, and this extended his stay. Prison security wasn’t quite what we know today, and Vidocq escaped. This began well over a decade of Vidocq escaping from prison; traveling around doing crimes; getting recognized by someone who knew him (whether jailer, policeman, or former co-conspirator); getting sent back to prison; then escaping again. His shortest stints on the outside were less than a day. His longest was four years.

Eventually, the authorities decided to save everyone a lot of hassle and sentenced Vidocq in absentia to be executed the next time he was caught. To save his neck, Vidocq turned informant. He started working as a stool pigeon for a canny officer named Jean Henry, called ‘the Bad Angel’. Vidocq, ever the charmer, had a knack for getting people to open up to him. He got fellow criminals to brag to him about the crimes they’d committed – including certain incriminating details – then passed the information to Henry. Vidocq was useful enough to Henry that the officer arrested Vidocq and threw him in prison. For two years, Vidocq maintained this tactic, getting fellow prisoners to brag about the crimes they hadn’t gotten caught for (which was most crimes, especially the serious ones), then passing those names to Henry. Vidocq gradually grew afraid his fellow prisoners would connect the dots about folks who’d gotten close to him, then were suddenly transferred and executed. So he convinced Henry – by now the chief of the Paris police – to let him out.

Vidocq became a police detective, working for the Bad Angel in Paris. He still had a death sentence on his neck, so there was no room for betrayal or escape. His primary method of gathering evidence was unchanged, except now he did it in a variety of clever disguises. He’d hang out in bars in bad parts of town, charm his fellow patrons, make friends, and get folks to open up and start bragging. He also served as an agent provocateur, convincing groups of poor men to commit crimes, then vanishing right as they did so and the law closed in. Whether that would be considered entrapment or not in a modern American context is an interesting question.

As Vidocq’s star waxed, so did his authority. He founded and headed France’s first police detective unit. He filled it with fellow ex-cons taught to use the same tactics he did. Vidocq’s unit enjoyed mixed success. On the one hand, it was effective – his agents could pass as criminals because they were criminals, and crime rates dropped as arrest rates climbed. On the other hand, old habits die hard and quite a lot of Vidocq’s plainclothes agents were themselves arrested, jailed, and even executed for crimes committed on and off the job.

Vidocq himself was no less controversial. It seems likely he used his new authority to punish his enemies. Co-conspirators who’d identified him to the cops when he was on the lam had a remarkable track record of getting arrested for death penalty offenses when Vidocq was around. He was almost certainly corrupt; his salary was excellent, but his growing wealth was astonishing. There were persistent rumors he directed thieves to particular establishments, accepted payment from the proprietors for the return of their goods, then split the profits with the thieves – and executed anyone who wouldn’t play along. There were equally persistent rumors he overlooked the crimes of thieves who paid him a ‘licensing’ fee. And he had a thriving business helping the wealthy avoid conscription by finding them substitutes (which was legal) – namely thieves to whom he could offer the choice of prison or the army (probably less legal, but I can’t say for sure).

Perhaps Vidocq’s most weirdly straightforward abuse of power was how he acquired the building material for his country estate. A bridge across the Seine had been destroyed during the wars. Vidocq convinced the relevant authorities that the rubble from the bridge was a hazard to navigation. Wouldn’t it be better if the stones were dredged up, then deposited on the property where Vidocq planned to build his house?

Vidocq was a bastard, and I wouldn’t want him in my city. Nonetheless, his methods worked. The year after he resigned (death sentence commuted by the King), crime in Paris rose 40%.

In 1819, Vidocq was the most famous policeman in France. So when authorities in the Somme decided they couldn’t get a handle on their bandit problem, they asked Paris very politely if they could borrow Vidocq for a while. In 1816, an inkeeper had been robbed and murdered by a group of bandits led by a 72-year-old woman, Prudence Pézé, nicknamed ‘the She-Wolf’: a canny, cruel woman dressed all in rags. The innkeeper would be the first of her many victims. In 1819 alone, nineteen people were found with their throats cut in the She-Wolf’s stretch of woods. The local police weren’t getting anywhere because none of the locals would rat out the bandits. This may have been out of fear of retaliation. It’s also possible the bandits looked after their neighbors to engender a sense of loyalty; it’s not an uncommon tactic. Either way, the local governor got Vidocq to come lend a hand.

Vidocq decided he would infiltrate the group, earn their trust, and lead them into a trap. Everyone knew bandits of this type (chauffers, ‘warmers’, named for their preferred torture technique) gathered information on targets from traveling peddlers. So Vidocq disguised himself as a peddler named Louis-Marie Frénot, nicknamed ‘Black Cap’. He let it be known in the right circles that he was willing to offer information for a price, and that he’d be traveling such-and-such a route through the forest at such-and-such a time if anyone wanted to recruit him. A local policeman would wait in the woods for any messages Vidocq needed to pass to the outside world.

After a long night tromping through the forest, Vidocq came to an isolated inn with good lines of sight up and down the road. Inside was an old woman with several rough-and-tumble-looking friends. They wanted information. Vidocq turned on the charm (especially towards the innkeeper’s daughter) and offered the bandits whatever they wanted to know – in exchange for a cut of the profits from any jobs he tipped them off to.

In January and February of 1820, Vidocq participated in three separate raids with the She-Wolf’s bandits. He avoided killing anyone (so he says) by feigning discomfort with it in the first raid. But the She-Wolf still didn’t trust him. So Vidocq did an end run around her, going to her second-in-command instead. This man, Fermin Capelier, nicknamed ‘Sabalair’, was a man of enormous body and simple mind. He saw Vidocq as a loyal friend. So when Vidocq told Sabalair of a well-off old man who lived alone in a walled house in the woods, Sabalair was all ears. The bandits scouted out the house and confirmed Vidocq’s report. The raid would occur on February 25th. Vidocq passed word to the police to be ready at the house to nab the bandits as they entered.

But the She-Wolf suspected something. At the last minute, she moved the raid to the 26th. Vidocq couldn’t pass the word. The police stayed up all night waiting for a raid that never materialized. In the morning, they left, disgusted. Fortunately, they returned the next night just in case. The police hid in the house, and Vidocq’s own local police contact lay in the old man’s bed, pretending to be him.

When the bandits forced their way into the house, they went straight to the bedroom. Sabalair went to shake the old man awake, only to have the ‘old man’ roll over and shoot at him! Sabalair tried to run, but there was another policeman in the doorway. Sabalair tried to strangle this one, but was stabbed in the back by a third, and then shot. As Sabalair lay on the floor bleeding, he demanded of his peddler friend: “Traitor, renegade, carrion, tell me your name.” He got a one-word response: “Vidocq”.

Most of the other bandits were rolled up in the operation. The She-Wolf was literally stabbed in the back, but managed to get back to her house. She was too old and too hurt to go farther, and was soon found. Sabalair died of his wounds two weeks later. The She-Wolf was executed alongside two of her comrades. The rest of the bandits went to prison.

When adapting this case to your fictional campaign, you’re obviously going to want to put your PCs in Vidocq’s role, infiltrating the bandits. Fear not, however! There’s still room for an NPC based on Vidocq. He can be the party’s local contact, the guy waiting in the woods and sleeping in the old man’s bed.

The adventure can be broken into five parts. First, the party has to work with their local contact to spread the word that they’re coming and should be recruited. Second, the PCs have to join the gang, charming your versions of either the She-Wolf or Sabalair. Third (optionally), the party joins a raid to prove themselves, while trying not to hurt anyone too badly. Fourth, when the date of the fake raid changes (for one reason or another), they have to get word to their local contact in time. Otherwise, it’ll be the real old man in the bed on raid night, and that would be a terrible tragedy. Fifth, you have the big fake raid and a climactic fight.

You’ll remember from earlier in this piece that police are a fairly modern phenomenon. At the time of these events, across the Western world, governments and private institutions were creating police forces, often with no local precedent for what such a thing should look like. Everyone was figuring it out as they went. That’s what makes the She-Wolf case so useful to us as GMs! The modern police procedural drama is deeply concerned with processes, regulations, and The Way Things Are Done. Basing an adventure on the She-Wolf case does not carry with it the same baggage. Vidocq just decided on his own how he was going to tackle the problem. At your table, an adventure based on the She-Wolf case does not even have to look like a police adventure. Your contact could just as easily be a political appointee, a concerned citizen, or a vengeful relative of a bandit victim. Given how contentious the role of policing in America can be, that might be exactly what you’re looking for.

Come back next week for another piece of early French police work!

–

Source: The First Detective: The Life and Revolutionary Times of Vidocq by James Morton (2004)