Since I was first exposed to D&D, I’ve thought it was neat that one of the languages you could be proficient in was “thieves’ cant,” a language for rogues. Real life and real languages are more complicated, but secret languages do exist, and they have been used in criminal activity. One such is Rotwelsch, a fluid, shifting language used by tramps and vagrants in the German-speaking world as far back as the Middle Ages. We’re not talking about the Roma; the closest American comparison would be hobo culture, which was actually influenced by certain features of Rotwelsch. We’re going to look at three historical Rotwelsch speakers who offered a window into this world of vagabonds—and, yes, thieves—and their itinerant culture. It’s a neat look at what a “thieves’ cant” looks like in the real world, where living languages have to be used for far more than petty larceny. And these three people make great NPCs for any adventure about investigating a crime or a vagrant-style mystery!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Rotwelsch is a sociolect: a language variant used by a social group, like a social class or an ethnic group that is nonetheless part of a larger culture. Think of it as a dialect, except where a dialect is spoken in a regional subset of a larger linguistic territory, a sociolect is spoken by a social subset of a larger linguistic culture. Rotwelsch is a sociolect for German-speaking vagrants: people who choose an itinerant lifestyle within the larger German-speaking world. The oldest surviving usage of the term “Rotwelsch” dates to around 1250. It’s influenced by Yiddish, Czech, French, Romani, and Latin (possibly from traveling Medieval students). As petty theft is one of the ways vagrants make their living, Rotwelsch made a convenient cover for crime, letting speakers discuss their criminal enterprises in the open. As a consequence, Rotwelsch has been repeatedly repressed by authorities from Martin Luther to Hitler.

One of the oldest windows outsiders had into Rotwelsch and the culture that spoke it was the testimony of a traitor to the vagabond community, Konstanzer Hans (1759-1793). Hans was a bit of a Robin Hood figure. He usually robbed government officials, so he could rely on the poor not to turn him in. But in 1782, a thief-taker named Jacob Schäffer caught Konstanzer Hans. Hans was carrying forged identity papers that meant Schäffer couldn’t prove Hans’ identity to the court’s satisfaction, so he pressured Hans’ dad to identify him. Father and son used to have a good relationship, once even talking to one another in Rotwelsch in front of a judge, perhaps to keep their stories straight. But the two had recently fallen out, and Hans’ father identified his son in court to avoid being looped in as an accomplice. To escape worse punishment, Hans revealed everything he knew about the region’s criminal underworld: safe houses, thieves, and fences. He even composed a small dictionary of Rotwelsch for the use of agents of the court. He became infamous as a traitor in the Rotwelsch-speaking community. He also attracted notoriety in polite society, when tale-spinners picked up his story and embellished it.

At your table, Konstanzer Hans is cool inspiration for a famous retired crook. He’s persona non grata in the criminal underground and his knowledge of personalities and locations is all out-of-date. But he still speaks the language, and his knowledge of how things worked “back in the day” is a good starting point—if the PCs can get him to talk.

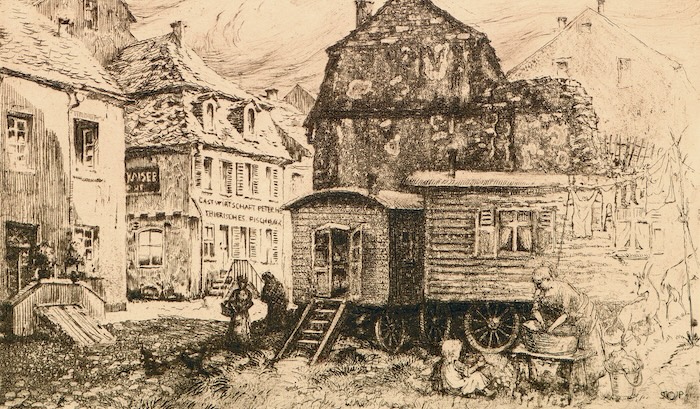

In 1843, a 25-year-old vagrant named Ferdinand Baumhauer was picked up for traveling with forged identity papers. He’d been a journeyman cobbler before he abandoned settled life, and was thus accustomed to carrying the regular paperwork that permitted journeymen to travel. His experience with papers and fine penmanship let him produce forgeries for his fellow tramps. His forgeries weren’t always very good, and he’d done time in prison before for forgery. In the 1843 arrest, Baumhauer was induced (probably with a beating) to give up the names of his friends and accomplices. The police then induced him to write scenes of life on the road, so they could better pursue their quarries. Baumhauer wrote his narratives in German, but with dialogue that shifted between languages as occasion demanded: usually Rotwelsch when vagabonds spoke among themselves, and other languages when interacting with outsiders. The protagonists of these little dramas are named Walter and Walteress, and they travel with a horse, wagon, and children. They beg, thieve, and peddle to get by. Lacking official permission to travel, they are forever having to escape the law. This was something the imprisoned Baumhauer himself understood; his book done, the police relaxed their vigilance and he escaped custody.

At your table, a fictional NPC based on Baumhauer the forger is a great source of information—if you can catch him! The PCs might see his book and learn how knowledgeable he is about vagrant society. He’s just the person to talk to about a particular case the party’s investigating. But first they have to find him. And as his collection of vagabond stories shows, Baumhauer knows a thing or two about not being found.

Image credit: Dietmar Rabich, released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Our last window into the Rotwelsch-speaking world is the so-called “King of the Tramps”, an anarchist, counterculture figure who tangled with Hitler himself! Gregor Gog bounced between a variety of jobs—merchant sailor, gardener, soldier in WWI—and eventually became a professional vagabond. In 1929, Gog called for an international meeting of tramps in Stuttgart as part of a broader attempt to get vagrants to organize and secure legal protections for their lifestyle. Despite a sizable police presence and the general disapproval of the residents of Stuttgart, six hundred vagrants attended the congress. Gog was involved in a vagabond journal, Der Kunde (The Vagrant), written partly in Rotswelsch. Surviving copies of Der Kunde offer a glimpse of the tramp lifestyle in the Weimar Republic and the vagabonds’ great love of their rootless existence. By this point, Gog was a controversial figure among vagrants. He’d built himself a cabin and wasn’t traveling much. He was happy to cash in on his unofficial title as King of the Tramps with documentary-makers and the like. Folks were of mixed opinions as to whether he was really still a vagabond.

The Nazis drew no such fine distinctions. When they came to power, vagrants were one of the first groups targeted. Gregor Gog was sent to a series of concentration camps before escaping to Switzerland, then on to Russia and Uzbekistan. As a new Soviet citizen, he was drafted into forced labor in Kazakhstan, released, then died in 1945.

At your table, a fictional NPC inspired by Gog is a great starting point for an investigation because he’s actually findable. He lives in a cabin; he may be King of the Tramps, but he leads a settled life and is a controversial figure for it. What information he has is limited by which vagrants will and won’t seek him out, but he probably knows someone who knows someone. Plus, he’s a really colorful character!

Make sure you don’t miss a blog post by subscribing to my no-frills, every-other-week mailing list! I also have a signup that’s only for big product releases!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need! Posts older than a year are behind a very cheap paywall – only $2/month!

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp. On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Blue Sky, I’m @moltensulfur.bsky.social.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on social media, or maybe emailing it to a GM friend of yours. The social media infrastructure that creators relied upon to grow their audiences is collapsing. You sharing my stuff helps me stay relevant and ultimately helps me get paid for my time.

Check out my book Making History: Three One-Session RPGs! It’s three awesome historical one-shots with pregenerated characters and a very simple rules system designed specifically for that story. Norse Ivory is a game about heritage and faith in the Viking Age. A Killing in Cahokia is a murder mystery in the Native American temple-city of Cahokia. And Darken Ship is a horror-adventure starring junior sailors on a U.S. Navy warship who wake up one morning to discover they’re alone on a ship that should carry three thousand.

Source: The Language of Thieves: My Family’s Obsession with a Secret Code the Nazis Tried to Eliminate by Martin Puchner (2020)