Let’s pick right back up where we left off last week! The ancient Roman historian Suetonius provides an amazing source for the foibles and eccentricities that can bring NPCs to life. His book The Twelve Caesars contains biographies of the first eleven Roman emperors and the proto-emperor Julius Caesar. Because the work is biography, not history, Suetonius was able to use his excellent sources to give us the quirks we as GMs need! As before, I’m omitting Suetonius’ reports of some emperors’ excesses with drunkenness, lust, and violence because they are (counterintuitively) boring. Last week, we ended with Claudius, so let’s roll right into Nero!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Of Claudius’ successor, Nero, Suetonius writes mostly of his violent excesses, sexual impropriety, and paranoia. But one interesting foible comes through: the man was way, way too into his hobbies. He made sure to attend every chariot race, and raced as a charioteer several times. As a musician, he competed in every possible competition of lyre and singing, focusing on it so much that he wouldn’t give speeches, to better preserve his voice. His attitude towards his fellow competitors was catty; to the judges, obsequious. Neither music nor chariot-racing were considered ‘appropriate’ hobbies for a man of his station, but both paled compared to his third hobby: street crime.

Suetonius assures us that Nero put on disguises to rob shuttered stores after dark and fence the goods. He prowled the streets looking for men to attack. If they resisted, he stabbed them to death, then dropped their bodies in the sewer. After an unrelated incident where he was beaten almost to death by a jealous husband, Nero took soldiers with him on his nighttime escapades. They hung back unobserved, ready to get involved if Nero fell into any real danger.

The next emperor, Galba, was the first Roman since Augustus to claim the metaphorical throne by force of arms. As governor of Nearer Spain, he rose in revolt against the deeply unpopular Nero. Nero committed suicide, and Galba proclaimed himself emperor. Civil war followed. In the span of a year, Otho (a general) replaced Galba, Vitellius (another general) replaced Otho, and Vespasian (a third general) replaced Vitellius, putting an end to the civil war and the Year of the Four Emperors.

Of Galba, Otho, and Vitellius, Suteonius tells us little. Galba was reportedly cheap and had such bad arthritis he could neither unroll a scroll nor wear shoes. Otho depilated his whole body and wore a toupee. Vitellius was witty but gluttonous. Galba receives high praise for his devotion to the state and the welfare of its citizens. Otho and Vitellius receive nothing but scorn.

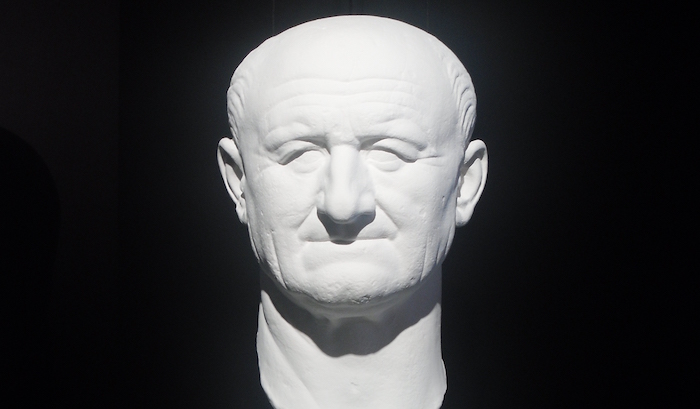

Image credit: Alessandro Antonelli. Released under a CC BY 3.0 license.

The man who overthrew Vitellius was named Vespasian. Unlike his predecessors, Vespasian was not from one of Rome’s great families. Inasmuch as this was possible in Rome, he was a self-made man, rising from the upper-middle class to the aristocracy. He was commanding the Roman forces in the First Roman-Jewish War when the Year of the Four Emperors began. After Vitellius seized power, Vespasian’s troops proclaimed their general emperor. Vespasian’s allies overthrew Vitellius, and this rather unassuming man ascended the throne.

Suteonius tells us Vespasian’s primary foible was his irrepressible sense of humor. He could not keep from cracking jokes, even about the most serious subjects, like the omens of his death. When a chasm opened in Augustus’ mausoleum, he quipped that it was for a certain aged descendant of the first emperor. When a comet appeared, he joked that the comet’s long tail looked like the long hair of the Persians and that the comet must be coming for the emperor of Persia.

Vespasian especially loved joking about the high taxes, extortion, and graft he used to refill the treasury after the (very expensive) Year of the Four Emperors. When his son Titus complained that Vespasian was taxing the contents of the city’s urinals, Vespasian quipped, “The urine may smell, but the money doesn’t!” Once a man with a lawsuit bribed one of Vespasian’s muleteers to interrupt the emperor’s travels to re-shoe the mules in a place where the litigant could talk to Vespasian. The emperor asked the muleteer what his re-shoeing fee was (turning the bribe into a joke) and insisted on being paid half. And once a man bribed one of Vespasian’s favorite servants to pretend they were brothers and recommend his ‘brother’ to the emperor for a political appointment. Vespasian sniffed out the lie, approached the man for the bribe personally, then quipped to the servant that “You’d best find another brother. The man you mistook for yours turns out to be mine!”

Vespasian was succeeded by his eldest son, Titus, the man who sacked Jerusalem and destroyed the Second Temple. Titus reigned for only two years before dying of fever. One of Suetonius’ stories about Titus hints at a foible, though whether it’s confidence, bravery, or a trusting nature, I cannot guess.

After becoming emperor, Titus swore he would never again be directly or indirectly responsible for a murder. When two senators were convicted of planning to kill him and take the metaphorical crown, Titus dismissed them with a warning not to try it again. Then he invited them to a dinner party with his friends. The next day, he invited them to sit close to him at a gladiatorial show. When the swords of the gladiators were brought before him, he passed them to the two senators to inspect: handing swords to two men who had just tried to kill him.

Image credit: Anagoria. Released under a CC BY 3.0 license.

Titus’ younger brother Domitian succeeded him: the last of Suetonius’ twelve Caesars. Suetonius doesn’t think much of Domitian, probably because he dramatically increased the power of the emperor at the expense of the upper classes (to which Suetonius belonged) and killed a bunch of rich and powerful people to keep it that way.

At the start of his reign, Domitian showed a number of eccentricities. He hated to walk or even to ride a horse. He was carried almost everywhere in a litter. He always attended gladiatorial shows with a little boy with “a grotesquely small head” whom he dressed all in red and spoke with very seriously. And he would spend hours every day catching flies and stabbing them with a pen.

Later in life, Domitian lost his hair. He was sensitive about it, and took as a personal offense all jokes about bald men. Despite this, he published a manual on hair care in which he described himself as “tall and comely”.

Domitian was an exceptionally keen archer, and liked to show off. Sometimes, he’d tell a slave to stand at a distance and hold out his hand with the fingers spread. Domitian would then shoot arrows between the slave’s fingers. Other times, Domitian would hunt game, often bringing down animals with two shots to the head arranged to resemble horns.

–