In my last post, I wrote about the character foibles of two of India’s Mughal emperors and how those foibles can make good quirks for memorable NPCs. Today I’m doing the second half of that thought with their successors, the last three of the truly great Mughals: the patron of the arts Jahangir, the mismanager Shah Jahan, and the zealous Aurangzeb.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

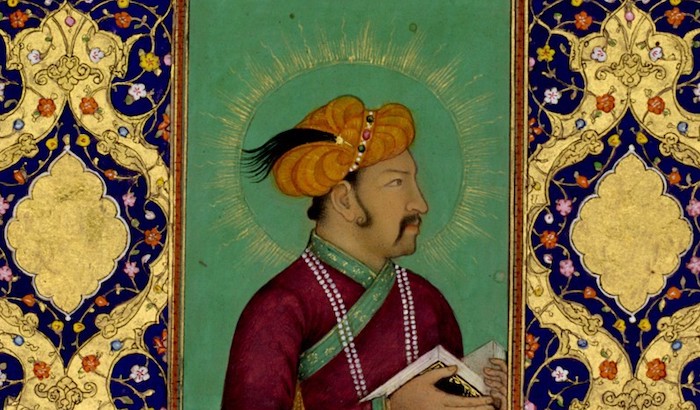

Jahangir wasn’t necessarily an effective ruler, but he inherited an empire in good condition and had great generals and advisors. So even if some things got a little worse under his reign, times were by and large good by the standards of the era. He was also renowned as a patron of the arts.

Jahangir was by inclination not a ruler but a scientist. He tested medical claims, like when he heard asphalt is good for broken bones and ordered a chicken’s leg broken and asphalt applied to it. (The asphalt didn’t help). He watched (and carefully documented) the egg-laying and baby-rearing of cranes. He measured all the interesting things he saw, from a big peach he received as a gift to a giant banyan tree. He performed dissections on interesting animals. And Jahangir wrote copiously on the natural world, from albino animals to conjoined twins to the philosopher’s stone—concluding that the latter is likely not real. He was, whenever possible, an empiricist, skeptical of poorly-documented miracles and overjoyed by the demonstrable facts of the universe.

Emperor Jahangir was an enthusiastic participant in the long-standing tradition of finding ironic or whimsical punishments for crimes. When a servant broke a china cup, he sent him to China to fetch another. He had two senior rebels sewed into the wet hides of two just-skinned donkeys, and made to look like donkeys, complete with heads. He sat the rebels backwards on two live donkeys and paraded them around the city until the hides shrank enough in the heat to kill the men inside by constriction. This punishment was an old one, dating back at least to 714.

The emperor was strongly influenced by his favorite wife, Nur Jahan. Her influence varied through his reign, anywhere from unofficial co-ruler to running the empire through her husband. This was despite the fact that, by law, Nur Jahan lived in the harem and no men but eunuchs and Jahangir could see her. She still participated in court life, hidden literally but not metaphorically. She hunted tigers from atop elephants in the usual style – save that her howdahs were enclosed, with just the tip of her musket peeking out. She rode into battle in a box slung between two elephants, giving orders through her eunuch servants.

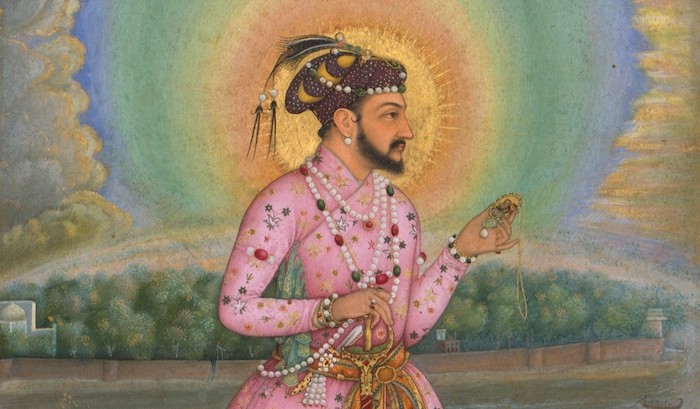

The next emperor, Shah Jahan, was less effective than his already-questionable father. His financial policies were ruinous, and his repressive religious policies inflamed dormant tensions. Still, he built the Taj Mahal as a mausoleum for his late wife, and that’s not nothing.

The only gameable foible of Shah Jahan’s I noticed was that he really liked gemstones. He was a world-class gem appraiser and collected stones as his hobby. A Portuguese missionary reported Shah Jahan preferred appraising gemstones to watching dancing girls. Supposedly, it would’ve take fourteen years to catalog his collection. Naturally, the gifts he gave and the gifts he preferred to receive were both gem-encrusted.

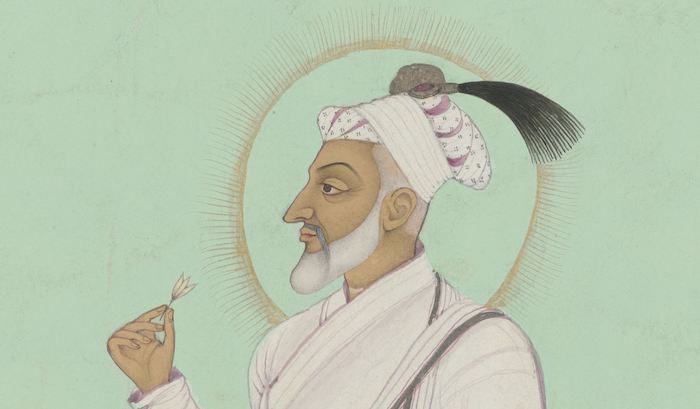

This brings us to the last of the really great Mughals, Aurangzeb, whom I actually touched on briefly in a post two years ago. As emperor, Aurangzeb was ruthless. He annihilated his family to secure his hold on power. As his sons grew up, he continually suspected them of plotting to seize power from him – which was fair, since he’d done it to his dad, Shah Jahan.

Aurangzeb was famously pious. From a policy angle, this was a problem, because India was even more multi-cultural under Aurangzeb than it is today, and many non-Muslims didn’t care for Aurangzeb’s version of religious law. Two laws in particular caused problems: technically, Aurangzeb was supposed to prohibit the construction of new non-Muslim religious sites (like Hindu and Sikh temples) and to demand a tax from unbelievers. Previous Mughals (except Shah Jahan, sometimes) had overlooked these laws in the name of civic unity. Aurangzeb wasn’t that sort of person, and his rule suffered for it.

Aurangzeb made his first, biggest show of public piety while in battle fighting the Uzbek Empire. The battle stretched into the hour of evening prayer, so then-prince Aurangzeb put down his sword, rolled out his mat, and knelt to pray while men bled and died all around him.

In most of his life, Aurangzeb wasn’t particularly imaginative, but one exception was his skill at information operations. In his war against his brother Dara, he recruited some of Dara’s generals, then smuggled fake letters into the tents of the loyal generals intended to be discovered so Dara trusted exactly the wrong people. Later, when one of Aurangzeb’s vassals tried to betray him and form an alliance with a different brother, that brother didn’t believe the vassal’s enticing letters, assuming they were more of Aurangzeb’s tricks. When his son rebelled against him and allied with the Rajputs (no friends of Aurangzeb’s), the emperor wrote the prince a letter saying, essentially, “Good job fulfilling our sneaky plan to bring the Rajputs onto the field of battle. Remember to put them in the front tomorrow when we fight so you can attack them from behind while I hit them head-on!” The Rajputs discovered the letter as expected, and the whole Rajput army vanished in the middle of the night. Aurangzeb’s son’s rebellion was suddenly a lot easier to crush.

So what kinds of NPC foibles do we have from these three historical figures? We have NPCs who:

– Love documenting, measuring, and testing interesting natural phenomena

– Seek ironic or whimsical punishments for wrongs

– Live publicly without ever being seen

– Have a great love of gemstones and are fine gem appraisers

– Are pious, even (or especially) when it’s not in their best interest

– Can make plausible-seeming letters fall into the hands of anyone, leading the reader to conclude exactly what the NPC intended

–

Make sure you don’t miss a blog post by subscribing to my no-frills, every-other-week mailing list! I also have a signup that’s only for big product releases!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need! Posts older than a year are behind a very cheap paywall – only $2/month!

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp. On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Blue Sky, I’m @moltensulfur.bsky.social.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on social media, or maybe emailing it to a GM friend of yours. The social media infrastructure that creators relied upon to grow their audiences is collapsing. You sharing my stuff helps me stay relevant and ultimately helps me get paid for my time.

Check out my book Making History: Three One-Session RPGs! It’s three awesome historical one-shots with pregenerated characters and a very simple rules system designed specifically for that story. Norse Ivory is a game about heritage and faith in the Viking Age. A Killing in Cahokia is a murder mystery in the Native American temple-city of Cahokia. And Darken Ship is a horror-adventure starring junior sailors on a U.S. Navy warship who wake up one morning to discover they’re alone on a ship that should carry three thousand.

Source: The Great Moghuls: India’s Most Flamboyant Rulers by Bamber Gascoigne (1971, revised 1998)