Duein fubara (‘foreheads of the dead’) are ritual screens used by trading houses of the Kalabari people of the Niger delta. These screens function spiritually as the bodies of important dead ancestors. Through the screens, the living can propitiate the dead to use their terrible magic powers for the benefit of the trading houses they helped found. In an RPG, you could use such a screen as an NPC. Let’s take a look!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

The Kalabari are an Ijaw-speaking group in Nigeria. In the 19th century, when the duein fubara were built, the center of Kalabari culture was the city-state of New Calabar on the Niger delta. The trading houses of New Calabar bought enslaved Igbo and Ibibio people in inland markets and resold them to European slavers waiting on the coast at Bonny.

The duein fubara were a creation of the slave trading houses. To found a trading house, you had to captain your own war canoe: a 30-man dugout with cannons fore and aft. Large trading houses had many subordinate houses working for them, each with its own war canoe. These war canoes fought in the incessant wars of the Niger delta. Many of these trading houses still exist, even after New Calabar tore itself apart in civil war and saw the end of the slave trade.

These trading houses maintained (and maintain) at least a duein fubara for the founder of the house, and sometimes several more. Each screen propitiates a single ancestor. It is a stand-in for the literal body of that ancestor. Most notably, it serves the same function as his forehead, which is where his teme lives. Teme is the part of a man’s soul that makes choices: his sovereignty, his free will, the rudderman of his canoe. By possessing the seat of the ancestor’s teme, the living members of the trading house can communicate with him, propitiate him with gifts, and ensure he uses his great and dangerous spiritual power for the continued good of the house.

A house keeps its duein fubara in a side room of its meeting hall. The room has no door; the screen must be able to see into the main room to monitor the affairs of its descendants and its house. A house head must make offerings to the screen every eight days to keep his ancestor happy. To show proper respect, he must first cleanse himself with the leaf of an odumdum tree. Then he offers gin, roosters, fish, goats, and plantains on mud pillars before the screen. Only then can members of the house ask the ancestral spirit for favors. If the head of the trading house is Christian, he may delegate to a non-Christian subordinate the task of sacrificing food and drink to this ‘pagan idol’, but he still must be present for the act.

The Kalabari are not hung up on whether the duein fubara are beautiful. What matters is if they’re recognizable to the relevant spirits. Thus, when carving a replacement for a screen that’s begun to decay, the sculptor will include all the same iconography and figural elements, but not be much concerned over whether the copy is identical. When carving a new screen, the sculptor must wait until the recently-dead man visits him in a dream to explain what his screen should look like.

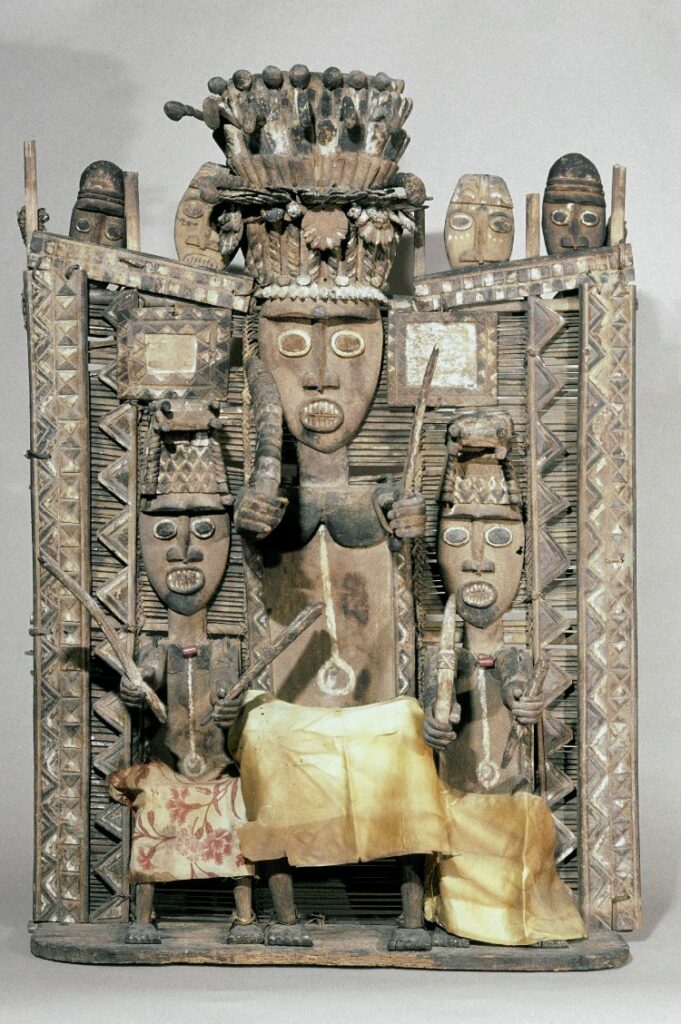

A duein fubara almost always has three figures carved in low relief and assembled from many separate pieces of wood. The central figure is the largest and is the subject of the piece; the flanking two are supporters or sons. The figures’ limbs are tied to them, and then the whole is attached to the backing of fiber slats with loops of twine. The figures’ feet rest on a baseplate. They’re dressed in cloth wrappings and hold objects in their hands, like spears, swords, and human heads. Since duein fubara faces are more or less identical, figures are identified by the ritual headdresses and masks they wear atop their heads and sometimes with relevant initials. The whole thing is surrounded by a wooden or bamboo frame. Small heads atop the frame represent followers of the house, and small heads along the baseplate are either children or vanquished enemies.

Most of the duein fubara in Western collections are held by the British Museum. Unusually for the famously pillage-heavy BM collection, its duein fubara were taken there at Kalabari request. Between 1914 and 1916, a Kalabari fundamentalist Christian cult threatened to destroy these hateful pagan artifacts. The heads of many of the trading houses surrendered their duein fubara to a British colonial officer to protect them from almost certain destruction. (No word on whether these houses would now like their screens back.)

It’s clear the users of the duein fubara didn’t see them as representing an ancestor. In a very real way, the screen is the ancestor, or at least his teme. This suggests an amazing idea: using duein fubara as NPCs. These NPCs are old, they have fearsome magical powers, and are very involved in growing the power and wealth of their families – provided they’re propitiated. So let’s have a look at some of the duein fubara in the British Museum collection and how they would function as NPCs!

We’ll start with one whose photographs somehow haven’t made it onto the BM website. Will Barboy was the founder of the Barboy group of trading houses in the mid-19th century. When Barboy was young, he fled from his enemies in New Calabar to Benin. When the king of New Calabar settled the matter and Barboy returned home, he brought with him wealth and slaves, and traded these into even greater fortunes. The semi-official nickname ‘Barboy’ came from his habit of waiting in his canoe just behind the river bar so he would be the first to trade with incoming British ships. His other nickname, ‘Oba’, (the title of the kings of Benin) referred to the many Beninese habits he acquired in exile. He was a violent man who led a tempestuous life, died young, and left a strong mark on the economic landscape of New Calabar. Barboy’s screen shows him wearing a ritual mask, carrying a spear, and resting his feet on the heads of his slaves. Cowries (a currency) in the frame allude to his legendary wealth, and the initials ‘BB’ worked into the background refer to his Barboy trading house.

Our next duein fubara (above) probably belongs to Otaji, called ‘Long Will’, Will Barboy’s brother and heir. His remarkable headdress jumps out at the viewer. That’s the headdress or mask of the Bekinarusibi (‘white man’s ship on head’) masquerade. This masquerade honors a jellyfish-like river spirit. The dance where the mask is worn is serious business, but is nonetheless more light-hearted than most such dances. In the late 20th century, dancers started putting bubble gum in the ship so it would fall out as they danced, much to the delight of children. All this suggests that Otaji was a more laid-back guy than his brother. But it’s worth noting he has another ritual mask at his feet on the right of the screen, this one unidentified. Associating yourself with two masquerades (and thus two river spirits and more influence in the dance society of respectable men) suggests ambition. He’s the nicer Barboy, but he’s still not to be crossed.

The above is the duein fubara of Manuel, founder of the Manuel trading house. He wears the headdress of the Ngbula masquerade. This masquerade honors the healing spirit Ngbula, and ordinarily can only be performed by a member of the Tyger Amachree trading house. Tyger Amachree, the house’s eponymous founder, won the dance from Ngbula when he met Ngbula’s wife (a mermaid), abducted her, and was confronted by the healer spirit. Manuel got special dispensation to dance this dance because he was Tyger Amachree’s nephew. Little about the screen suggests Manuel’s own accomplishments, mostly just his association with his better-known uncle. Now, in the afterlife, is Manuel jealous of his uncle’s success? Or is he ferociously loyal, even to the detriment of his own house?

We’re going to close with another duein fubara whose pictures haven’t made it onto the BM website. We don’t know the identity of this man, but he’s dressed as the high priest of Owamekaso, the national goddess of New Calabar. What’s weird is that Owamekaso is a peaceful deity who loves children and hates bloodshed – and her priest is depicted here carrying a spear and a knife. The held objects of the screens in the BM collection may have gotten mixed up at some point, it’s unclear. But if these are the right implements, if the high priest of a peaceful goddess carries weapons, it suggests he may be a man who believes in maintaining peace through the threat (or use!) of force. Convinced of the rightness of his cause, is there anything he won’t do to protect the helpless? And what happens if he pegs the PCs as ‘the wrong sort’?

–

Source: Foreheads of the Dead: An Anthropological View of Kalabari Ancestral Screens by Nigel Barley (1989)