Sometimes, you want to play a soldier, even when no one else does. Ming warriors looked snappy on parade, Green Berets have access to cool weapons, and Gurkhas are just plain badass. But soldier PCs can’t go where they want or behave as they will. This problem can be mitigated when the whole party’s a military unit, but what if only one PC is a soldier? The remarkable life of Loreta Janeta Velázquez provides us a solution!

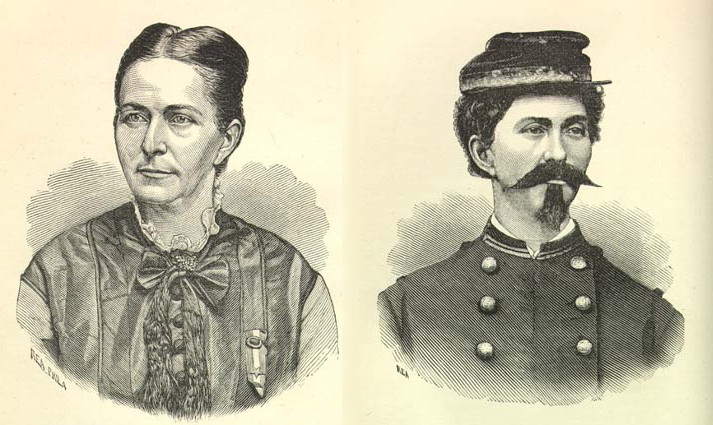

Loreta Janeta Velázquez was born in Cuba to wealthy parents. As a child, she loved Victorian novels about the Female Warrior Bold and fantasized about being a soldier. She abandoned Cuba to elope with an officer in the U.S. Army. Living with him on a variety of forts familiarized her with Army affairs. When the Civil War broke out, Velázquez saw the opportunity for adventure! She disguised herself as a man, put on a Confederate uniform, invented the identity of Lt. Harry T. Buford, and rode off to war. (For more on female soldiers in the American Civil War, see last week’s post)

The first thing she did was use her considerable personal wealth to raise an independent company. Such companies were not uncommon on both sides in the Civil War. They were entirely funded by private citizens, who often commanded them. When Velázquez’s self-imposed term of enlistment ended after three months, she handed command of her company to an associate and rode for Virginia.

Velázquez arrived in Virginia as Lt. Buford without a position in the Army or soldiers to command. In the modern military, this would be unthinkable, but the early part of the American Civil War was a chaotic time. The mere fact of having been a lieutenant commanding a company was good enough for her to get away with calling herself ‘lieutenant’ – even though she held no formal officer’s commission from the Confederate States of America. She took charge of a company missing its officers and led them in battle at Blackburn’s Ford in July 1861, then fought again three days later at the First Battle of Bull Run. After Bull Run, Velázquez was unable to secure a regular (officially sanctioned) army commission, so she left for the western theater. She fought at Fort Donelson and was wounded at Shiloh.

For all that she wanted to be a soldier, Velázquez didn’t seem to possess any tolerance for drudgery. She was restless, impulsive, and impatient. She moved from unit to unit in search of action – and often found it. Had she stayed with one unit long enough to prove herself, she might have obtained the regular commission she craved, but she never did. In 1863, she decided (in her words) that she “was doing no very material service by plunging into the thick of a fight, as much for the enjoyment of the thing as for anything else.” So Velázquez left the military to become a spy.

She spied for the Confederate Secret Service for about a year and a half, much of it as a man. She hunted spies in Richmond, procured supplies from her native Cuba, and carried messages to Confederate sympathizers in Union-occupied territories. She even spent six months as a double agent in Washington, D.C., pretending to work for the Union, but actually passing information to the Confederacy. She even plotted unsuccessfully to assassinate President Lincoln. In espionage, Wakeman likely found the excitement she craved.

Over the course of her military and spy careers, Velázquez was arrested three times for transvestitism, which was a crime. Nonetheless, she was generally successful at passing as a man. As a woman of means, she could get her uniforms tailored to hide her figure. She wore wires under her shirt to fill out her chest and shoulders, and sometimes a false mustache. Many female soldiers in the Civil War took up traditionally masculine vices on campaign to help fit in, but ‘Lt. Buford’ avoided vulgarity and drink. She was afraid she might reveal her true identity while drunk. She did, however, court young women, claiming it might have attracted attention had her alter ego not done so.

Velázquez left Confederate service shortly before the war’s end. Her first husband had died quite early in the war, and she remarried almost immediately. That husband either died or fled the Confederacy, and she married a third time shortly after the war’s end. She and that husband emigrated to Venezuela, where he died of disease. She moved to Texas, got married a fourth time, and had a child. He fourth husband soon died or abandoned her, and Velázquez was left to raise their child alone. The last credible mention of Loreta Velázquez and her child comes from 1878, while she was living in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, working as a newspaper reporter.

–

The story of Velázquez and Lt. Buford is a thrilling adventure, and we can learn a lot from it for the gaming table!

Let’s say you want to play a soldier in an RPG. That’s a sensible choice, and a lot of fun! But soldiers can’t go where they want to follow the plot. They have orders to follow. It’s hard to be a soldier and an adventurer.

Lt. Buford offers us a way out. Irregular officers don’t have this problem. A PC who raised an independent company – or even just showed up in the right uniform and said “Put me where you need me” – can leave any time she wants. As soon as the plot takes you elsewhere, you’re gone. You can even leave soldiering behind, like Velázquez did when she became a spy. You get all the fun of playing a soldier character, with few of the restrictions on your actions. There seem to be two requirements for such a character, though:

– She has to be familiar with military affairs, since she will receive no formal training in them. Maybe, like Velázquez, she was exposed to them in a previous part of her life. Maybe she reads a lot. Maybe she just has a knack for it.

– She has to have money. Raising your own company isn’t cheap, but it gives you legitimacy. Even if you don’t bring it with you, that first company you raised is your foot in the door to being able to claim to be an officer.

–

Source: Blanton, DeAnne, and Lauren M. Cook. They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War. , 2002.