This is part 2 of a 4-part series about the wars of Julius Caesar. We started with his nine-year conquest of Gaul. This week, we’ll finish up the Gallic War, then move move into the civil war against his former ally Pompey! Future entries will cover his involvement in an Egyptian civil war that placed Cleopatra on the throne and his defeat of Pompeian rump states in Spain and North Africa.

As before, my focus is on moments when individual people impacted the outcomes of battles and of entire campaigns. The standard advice for doing giant battles at the table is to give your PCs a special task that has a big impact on the fight: assassinate an enemy general, take a particular tower that can be used as a signal post, scout out enemy snipers, etc. Caesar’s wars are full of these moments.

Our story resumes in 53 B.C. By this point, Caesar had conquered all of Gaul, but Gaul refused to stay conquered (imagine that!). So Caesar changed his strategy. He began to act as though he were the governor of all of Gaul, not just the southern sliver Rome had granted him. He treated the various Gallic chieftains as his subordinates. He levied taxes and armies from them. When they inevitably rebelled, he crushed them. The revolts got worse and worse (most notably the campaign of Vercingetorix), but Caesar always managed to come out on top. Every victory left him wealthier and more popular. Some of Caesar’s enemies in Rome pointed out that this was all flagrantly illegal, but no one stopped him. After all, he was winning!

In the sixth year of the war, Caesar dispersed his forces to conduct a systematic genocide against a particularly rebellious group of Gauls. During this time, he left his sick and wounded soldiers and his baggage train in a fort where they would be safe. Interestingly, a Roman unit had been wiped out at this very site the previous winter. The more superstitious of the soldiers in the fort weren’t thrilled to be occupying ground that might be cursed or haunted.

At the same time, a band of Germans crossed over into Gaul to participate in the genocide and looting. They were theoretically on the same side as the Romans here, but when they heard about the Roman baggage train, they thought it was too juicy a target to pass up. The Germans rode for the fort. Against Caesar’s orders, the fort’s commander was letting people come and go through an open gate. No one noticed the Germans until they were almost on top of the fort.

Heavy fighting broke out around the open gate. The battle was on a knife’s edge – the Germans were almost inside. One of the sick soldiers in the fort was an older, heavily-decorated, highly-ranked veteran named Sextius. Because of his illness, he hadn’t eaten in five days. Nonetheless, when he saw how close the fighting was, he snatched weapons from nearby soldiers and went to the gate. The centurions of the cohort on guard duty followed him. These men held the line until a proper defense could be mounted. Sextius was heavily wounded and passed out, but the soldiers around him passed him hand-over-hand to get him out of the fighting, and he survived. The Germans were forced to withdraw.

If you want to put your PCs in the thick of the fighting, this vignette shows you can boil an entire battle down to a single scene. This one moment – Sextius and his comrades defending the gate – will decide the outcome of the entire battle. You might put your PCs in a part of the battle line that’s holding up OK, but they can see another section where the line is starting to buckle. If the party scoots over there and holds the line (effectively single-handedly) for five rounds of combat, the defenders will have a chance to reorganize and the battle will be won. Otherwise, the day is lost. Make sure the players know about the five-round countdown clock. It keeps things tense. If you keep the goal secret, this fight will instead feel like an interminable slog.

In the seventh year of the war, a Gallic king named Commius plotted to betray the Romans. Caesar had appointed Commius king of his people after Caesar defeated them in battle, and Commius had given Caesar several years of loyal service. But a major anti-Roman uprising was brewing, and Commius wanted to join. One of Caesar’s commanders, a man named Labienus, got wind of this betrayal. On his own initiative, he tried to have Commius assassinated.

Labienus sent a team of Roman soldiers to Commius for a meeting. When the lead soldier grasped Commius’ hand, the other soldiers attacked! One soldier gave Commius a bloody head wound, and the Romans withdrew. They thought they’d killed Commius. Actually, they’d botched the job.

When Caesar put down the aforementioned uprising later that year, Commius refused to surrender. The Romans had tried to assassinate him once before. Surely they would behave equally dishonorably once he was their prisoner. Instead, Commius fled and led a guerrilla resistance to Roman rule. Commius’ insurgency didn’t amount to much, but it prolonged the war, bringing harm to Commius’ people before his inevitable defeat.

If your PCs are sent on an assassination mission like this one, they may do things differently. They may successfully kill your version of Commius and weaken the upcoming uprising. Or they may refuse to carry out their orders, which are a violation of every norm of warfare and diplomacy. Inviting people to meetings and killing them is a great way to stop other people from agreeing to meet with you in the future, which serves no one’s interests. If the PCs meet with Commius and refuse to kill him, your version of Labienus will be livid, but your version of Caesar will likely not be. And it will keep Commius from starting a guerrilla war later, thereby paying dividends in the long run.

The Portable Antiquities Scheme/ The Trustees of the British Museum. Released under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

By the ninth year of the war in Gaul, things had wound down. Gaul was depopulated – more than a million Gauls died, and perhaps a million were enslaved. The survivors were exhausted, and completely subjugated. So Caesar turned his eyes southward, back towards Rome.

For decades, Rome had been alternating between rule by the Senate and by military strongmen. Two men had eyes on being Rome’s next dictator. One was Caesar. The other was Pompey, once Caesar’s longtime ally, now his bitterest rival. Both were military geniuses. Caesar was famously the conquerer of Gaul, but Pompey had equally great conquests in Asia Minor and the Levant. Both men commanded large armies whose primary loyalty was to their general, not to Rome.

When their political alliance broke down, Pompey took advantage of Caesar’s absence from Rome to ram through the election of two pro-Pompey partisans to the position of Consul. Rome had two consuls elected to single-year terms and possessing great executive power. The election cost Caesar any control of the political process in Rome. There was no longer any way for Caesar and Pompey to coexist. Caesar gathered his armies and marched on Pompey.

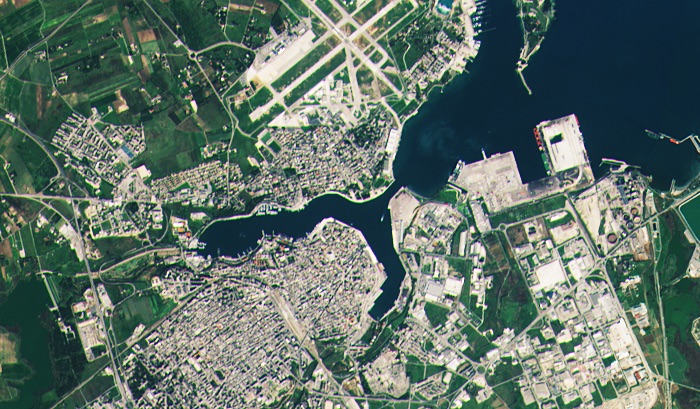

Pompey and his army retreated to Brundisium (modern Brindisi, in the boot heel of Italy). He loaded half his troops on ships and sent them across the Adriatic to safety. His plan was to wait for the ships to return, then cross with the rest of his troops.

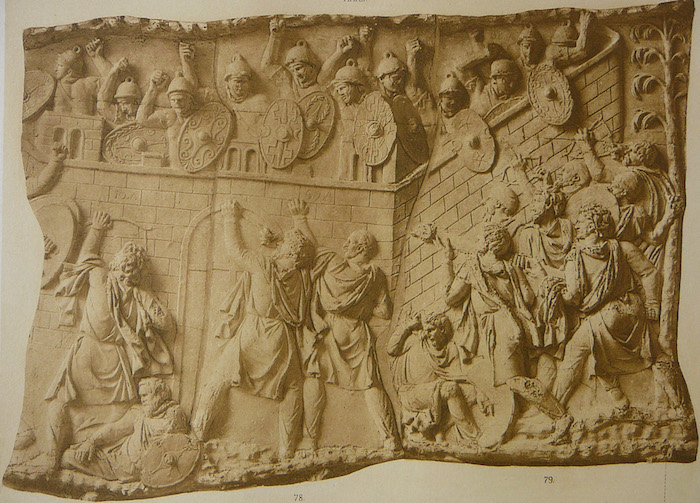

Before Pompey could leave, Caesar arrived with his army outside Brundisium. He started building a fortified pontoon bridge across the mouth of the harbor, complete with a dirt floor (to protect against fire arrows), wicker walls (to protect the builders), and towers (to shoot at approaching ships). Pompey, meanwhile, outfitted the few ships in the harbor with catapults and three-story towers, and sent them against Caesar’s floating fortifications daily.

While all this was happening, Caesar still sought a way to resolve his political differences with Pompey without plunging the state into civil war. If Pompey would agree to mutual disarmament and a resumption of their alliance of convenience, Caesar would call off the siege. So against the backdrop of naval siege warfare and insane feats of military engineering, Caesar sent an envoy into the city.

The envoy had a close personal connection to one of Pompey’s admirals. He was supposed to leverage this relationship to orchestrate a face-to-face meeting between Caesar and Pompey: a last ditch attempt to salve both men’s egos and ambitions before they tore the state apart. The envoy failed. Pompey seized on the pretext that his pet consuls weren’t present, and only they could legally endorse a political compromise. This was technically true, but in a realpolitik sense, Pompey was already dictator of Rome, and legal distinctions had been moot for months. When Pompey’s ships returned, Caesar’s pontoon bridge/wall wasn’t yet done. Pompey and his forces escaped Brundisium, and the Roman state descended into a four-year civil war.

At your table, you could have a great roleplay encounter if your PCs serve as envoys on the eve of a battle, particularly against the backdrop of colorful and interesting violence. Where Caesar’s envoy failed, maybe your PCs will succeed, and prevent the appalling (but entertaining in fiction!) nightmare of war.

–

When part 3 drops next month, we’ll continue the story of the Roman Civil War with more moments where individual people changed the course of battles and campaigns! In the interim, we’ll have more normal, standalone posts!

–

Source: The Landmark Julius Caesar, a collection of works written by Caesar and his contemporaries, edited by Kurt A. Raaflaub and Robert B. Strassler (2019)