This is the final installment in a 4-part series about the wars of Julius Caesar. We ended the last post with Caesar’s political rival Pompey dead, and Caesar gearing up to pursue the last of Pompey’s loyalists across the Mediterranean. This week, we conclude the story!

As before, my focus is on moments when individual people impacted the outcomes of battles and of entire campaigns. The standard advice for doing giant battles at the table is to give your PCs a special task that has a big impact on the fight: assassinate an enemy general, take a particular tower that can be used as a signal post, scout out enemy snipers, etc. Caesar’s wars are full of these moments.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Image credit: Andrew Bossi. Released under a CC BY-SA 2.5 license.

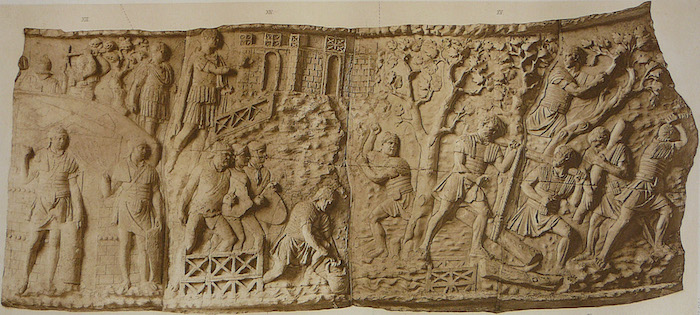

Caesar spent less than a year consolidating control over Italy, Rome, and Pompey’s former possessions in Asia. Then he sailed for modern-day Tunisia, where the last remnants of Pompey’s loyalists were holed up. Caesar’s first battle in Tunisia, at a place called Ruspina, shows him at his very best. Faced with a far larger force of Numidian cavalry using tactics unknown to Caesar, he improvised a novel defense, drew out every last ounce of effort from his troops, and somehow kept his forces from breaking during an awful, daylong marathon of a battle. But the highlight of the battle from a gaming perspective centers around the Pompeian general: Labienus.

Labienus used to be Caesar’s second-in-command. Throughout the Gallic Wars, Labienus was a loyal subordinate, assistant, and commander in his own right. In Caesar’s account of the war in Gaul, Labienus appears again and again as a sort of mini-Caesar. He displayed the same traits that made Caesar so effective: speed, decisiveness, initiative, and a deep concern for the wellbeing of his troops. Labienus learned from the best!

But when the Roman civil war began, Labienus sided with Pompey. One possible explanation could be that Pompey offered Labienus something Caesar couldn’t: a truly independent command. Under Pompey, Labienus could win his own victories, earn his own glory. So he took the chance.

It didn’t work out. By the battle of Ruspina, Pomey was dead. Caesar was the dictator of Rome. And Labienus proved unable to beat his mentor, even when he had every advantage. It’s almost a cautionary tale about knowing your own limits: a warning about being merely good in an era of greats.

At one point during Ruspina, Labienus rode along Caesar’s battle line without his helmet to intimidate Caesar’s troops. These were soldiers who knew Labienus, who’d fought under him on a hundred Gallic battlefields. He called out to one soldier standing beside an unfamiliar standard, “You’re just a raw recruit! How’d you find yourself in this pickle? Did Caesar bewitch you with those speeches of his? By Hercules, I feel sorry for you!” But the soldier was no raw recruit. He was a veteran of Caesar’s famous 10th legion, temporarily augmenting another unit, and told Labienus so. Then the soldier took up a javelin and hurled it at the Pompeian general. The javelin caught Labienus’ horse full in the chest. “There’s your damned proof of who I am!”

This incident had little impact on the awful slaughterhouse that was Ruspina. But it’s a remarkably human moment on the battlefield, and you can put your PCs on either side of one like it. If your party is well-known, their general might ask them to ride out and intimidate the enemy. If your PCs know anyone on the other side, it’s a perfect opportunity for a little back-and-forth roleplay. On the other hand, maybe it’s an enemy recurring NPC on horseback, and the PCs in the lines. This works especially well if that NPC’s latest plot arc has concluded and you wouldn’t have any heartburn over the PCs killing her outright with a lucky shot.

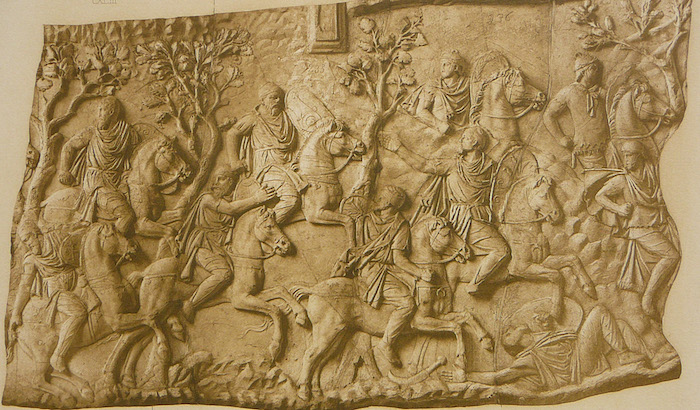

After Ruspina, both sides delayed for almost a month to bring in reinforcements. Then Caesar stole a march on the Pompeians in the middle of the night. His forces scaled a long ridge that overlooked the plain on which the Pompeian camp lay. Along the ridge were a string of old towers. Only one was manned; the Pompeians were using it as a lookout post.

Caesar immediately ordered the construction of a wall running the length of the ridgeline, about halfway down the slope towards the enemy camp. Caesar’s troops were combat engineers to a man and worked fast. But the Pompeians soon noticed what was happening under cover of darkness. They rode out in force and soon would be upon the incomplete fortifications. Caesar needed a diversion – something to distract the enemy cavalry until the wall was finished.

So Caesar sent one of his own cavalry squadrons to drive the Pompeians from the one tower they controlled. This small force was successful, and soon wounded Pompeian tower guards were streaming down the hillside. In ancient warfare, fleeing troops were incredibly vulnerable. Labienus (the same Labienus from above) took the entire right wing of the Pompeian cavalry to cover the tower guards’ retreat. With the enemy cavalry split up, Caesar was able to defeat them in detail, though Labienus got away again. The wall went up successfully.

This wall wound up forming the core of a defensive line that nullified the Pompeians’ numerical advantage. Indeed, Caesar’s defenses were so formidable that the Pompeians refused to commit to a pitched battle. After two months of skirmishes and stalemates, a disgusted Caesar took his army elsewhere. Maybe he could find someplace else where his theoretically superior foes would actually be willing to fight him.

At the gaming table, ‘go take that small but strategically-important spot’ is a great task for PCs on the battlefield. The trick is finding a reason why the PCs must be the ones to take the spot. If it’s so important, why not send a larger force? Here, Caesar gives us a perfect excuse: the larger army is needed for construction! Sending more troops would slow down construction, defeating the entire purpose of the diversion! At your table, sending your PCs to take a tower and divert the enemy cavalry could be a great way to give a traditional RPG objective (‘go kill things in that tower’) serious battlefield consequences!

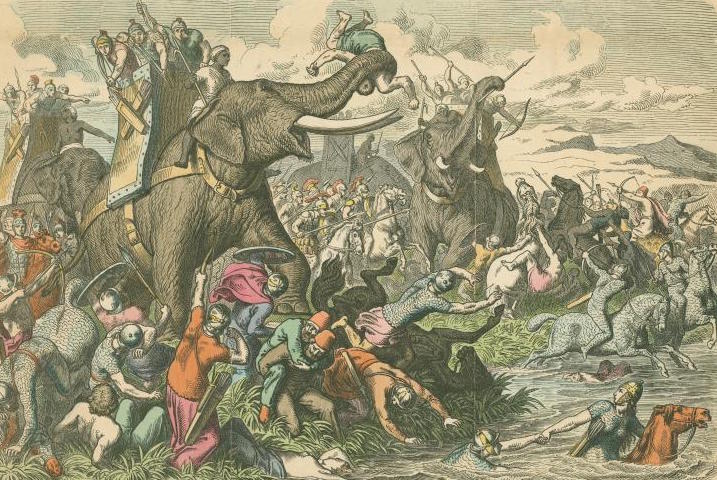

Caesar eventually found that battlefield, and there he dealt a decisive blow against the Pompeians. His enemies brought elephants to this battle, but Caesar was ready for them. He’d ordered circus elephants brought over from Rome. His soldiers learned where to attack an elephant by throwing blunted spears at the example creatures. So when the battle was joined, Caesar’s slingers showered the Pompeian elephants with stones and lead bullets. The beasts panicked and fled, rampaging through their own lines.

For this next part, I’m going to quote the anonymous author of The African War, who was probably an eyewitness to this battle:

“I ought to mention the gallantry of a veteran soldier of the Fifth legion. On the left wing an elephant, maddened by pain, had attacked an unarmed camp follower, pinned him underfoot, and then knelt upon him; and now, with its trunk erect and swaying, and trumpeting loudly, it was crushing him to death with its weight. This was more than the soldier could bear; he could not but confront the beast, fully armed as he was. When it observed him coming towards it with weapon poised to strike, the elephant abandoned the corpse, encircled the soldier with its trunk, and lifted him up in the air. The soldier hewed with his sword again and again at the encircling trunk with all the strength he could muster. The resulting pain caused the elephant to drop the soldier, wheel round, and flee with shrill trumpetings.”

You can totally use this scene as-is: during your battle, an enormous enemy monster appropriate to your setting is slowly killing an unarmed porter, cook, merchant, or prostitute. Do your PCs drive it off? Alternatively, the party could be tasked with seeking out a particular huge enemy monster on the battlefield and killing it. Either way, the combat is a traditional, D&D-style ‘one huge creature vs. the whole party’. While you should make frequent reference to the larger battle raging around the party, it’s really just set dressing.

After their defeat in Tunisia, the Pompeians fled to Spain. Caesar had to stop in Rome to deal with some political business, but he was soon in hot pursuit. He wrapped up this campaign in three months. Labienus died in the decisive battle at the end. Caesar joined him in death a year later, dispatched by a conspiracy of senators trying desperately to save the Roman Republic.

Thank you for joining me on this four-part biographical/military-historical tangent! It was a lot of fun to write, and I hope you found it an entertaining – and useful – read! Do you have thoughts about recurring NPCs in warfare, diversions, or war elephants at the gaming table? Have you ever tried anything like this in your own campaigns? Come tell me about it over on Facebook or Twitter!

–

Source: The Landmark Julius Caesar, a collection of works written by Caesar and his contemporaries, edited by Kurt A. Raaflaub and Robert B. Strassler (2019)