Last month we looked at nine bizarre occult NPCs from 1600s Britain, taken from a wonderful historical source: Aubrey’s Brief Lives. This week we return to the Lives for eleven scholarly NPCs, and – as before – we’re less interested in the real biographies of these people than in the gossip Aubrey reports about them. One NPC is a blood scientist who’s clearly a vampire. One’s a demographer marooned on foreign shores for being too smart. One’s a globe-trotting soldier who uses chemistry to get out of trouble. All are wild stories in their own right and are perfect to fictionalize and drop into your ongoing campaign!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Sir William Petty (1623-1687) was a political economist, statistician, and demographer – one of the first! He went to sea as a cabin boy, but the bright and precocious youngster was so intimidating (or so annoying) that his fellow sailors marooned him in Normandy with a broken leg rather than continue the voyage with him aboard. Conveniently, this allowed Petty to study on the continent; he later called his marooning “the most remarkable accident of life,” but otherwise didn’t like to talk about it.

In 1650, a serving maid named Nan Green was hanged for murder. After she was cut down, she was carted off to be dissected by some anatomists; dissecting humans was considered borderline monstrous, but letting anatomists work on criminals was an acceptable compromise. Petty came upon Green’s body and found she wasn’t quite dead! He brought her back, much to the astonishment of all.

In 1660, Sir Hierome Sanchy challenged Petty to a duel. Sanchy was a soldier and Petty nearsighted, so things weren’t looking good for the statistician. As the challenged party, Petty got to pick the weapons and the place of battle. He chose carpenter’s axes and a dark cellar to even the odds. Petty’s choices embarrassed Sanchy and the soldier withdrew his challenge.

During one of the Anglo-Dutch wars, London sent a commissioner to Ireland to raise a levy of 1,500 sailors for the Navy. Petty was in Ireland using his mathematical prowess to squeeze lucre from the conquered Irish. He told the commissioner he’d never find that many sailors in Ireland, “for he knew how many tons of shipping belonged to Ireland, and the rule is, to so many tons so many men. Of these ships half were abroad and of those at home, so many men unfit. In fine, the commissioner with all his diligence could not possibly raise above 200 seamen there.” For the era, this was a remarkable feat of economic statistics.

In 1665, Petty presented a paper on shipbuilding to the Royal Society. The paper proved so insightful that the president of the conference confiscated it, “saying ’twas too great an arcanum of state to be commonly perused” – that is to say, that its conclusions were so valuable for English sea power that the paper must not be kept where any Dutchmen might read it.

An NPC based on Petty might be a highly-placed analyst who regularly gets himself into trouble and needs his friends to bail him out. Because his work is so vital to the government, any efforts by the PCs to save him from his latest duel challenge (or assassination attempt by an Irish-analogue patriot) might earn them a favor from someone important. Plus there’s the question of whether your Petty-analogue NPC can raise the dead. Some people say he’s just got a knack for medicine, but that executioner swears Nan Green was dead when he cut her down.

Sir Walter Raleigh (1552-1618) is relevant to this post for his work as a chemist, though he’s better-known as a military commander and adventurer who fought for England in France, Ireland, Spain, and Guyana and helped found the first Virginia colony. He was a great favorite of Queen Elizabeth, and when she died he fell rapidly from grace. He was imprisoned for treason and ultimately executed.

Raleigh’s chemistry work was done most notably during his long sea voyages, when he had lots of time to kill. He always carried a trunk full of books with him and, presumably, some alchemical equipment. While awaiting transfer to the prison at the Tower of London, he used his skill at chemistry to make it seem like he’d come down with leprosy. He hoped that this would delay his transfer and give him a chance to escape. Unfortunately, a doctor declared him healthy enough to move, so this ruse came to naught.

It was persistently rumored Raleigh was an atheist. Aubrey heard from his cousin that, on the scaffold, Raleigh delivered a long speech in which “he spoke not one word of Christ, but of the great and incomprehensible God, with much zeal and adoration, so that he concluded he was an a-Christ, not an atheist.” The speech was surely made more interesting by the fact that Raleigh talked like a pirate. He had a broad Devon accent, similar to the Dorset accent that actor Robert Newton exaggerated in Treasure Island (1950) and has since devolved into the stereotypical ‘pirate’ accent. (Though let’s acknowledge that accents change over time, and a Devon accent in 2021 probably sounds quite different from one in 1618.)

As a scholarly NPC, Raleigh is best when combined with Robert Boyle (1627-1691). He’s best known today for his eponymous law about the relationship between a gas’ pressure and volume. Boyle paid great sums of money for foreign chemistry texts, and many foreign chemists traveled to England to speak with him. In an era where chemists were secretive and kept their discoveries close, Boyle was something of a spymaster.

Raleigh and Boyle really do combine well to make a single, more-interesting NPC: a pirate-talking chemist who’s traveled the world on military and spy adventures, now fallen from favor, reduced to using alchemical trickery to stay out of prison. He might offer the party fabulous knowledge to spring him from jail – or his enemies at court and abroad might pay to have him silenced permanently.

Ralph Kettell (1579-1643) was a scholar of divinity and president of Trinity College, Oxford. He was a strange man, almost a Dumbledore figure, as clever as he was eccentric. Says Aubrey: “Dr. Kettell’s brain was like a hasty-pudding, where there was memory, judgement, and fancy all stirred together. He had all these faculties in great measure, but they were all just so jumbled together. If you had to do with him, taking him for a fool, you would have found in him great suitability and reach; é contra, if you treated him as a wise man you would have mistaken him for a fool.”

He liked to interrupt lectures to say weird things like “I will show you how to inscribe a triangle in a quadrangle. Bring a pig into the Quadrangle of the college, and I will set the college dog at him, and he will take the pig by the ear, then come I and take the dog by the tail and the hog by the tail, and so there you have a triangle in a quadrangle!” If students didn’t respond to his educational interruptions as he expected, he’d grow flustered. To quote Aubrey, “Now come we, I say the fox’s tail is a horn: is this a true proposition or no? (to one of the boys) Yes, said he. The doctor expected he should have said ‘no’, and it put him out of his design. ‘Why then,” said he, ‘take him and toot him’, and away he went.” And if he couldn’t induce you to play his games, he was utterly flummoxed. In the English Civil Wars, he was much grieved “to be affronted and disrespected by rude soldiers. I remember being at the rhetoric lecture in the hall; a foot soldier came in and broke his hourglass.”

A great example of Kettell’s eccentricity was the nonsensical eulogy he delivered at the funeral of a beloved friend of the school: “He was the finest sweet young gentleman. It did my heart good to see him walk along the Quadrangle. We have an old proverb that ‘hungry dogs will eat dirty puddings’, but I must needs say for this young gentleman that he always loved sweet, he spake it with a squeaking voice, things, and there was end.” For more eccentricity, he hated people in white hats, for he thought they were drunkards. He hated long hair on men and would cut it off by surprise. He believed powdered wigs were the scalps of men cut off when they were hanged. And he insulted idle college boys as “turds, tarrarags, Rascal-Jacks, blindcinques, [and] scobberlotchers.”

Yet all of Kettell’s silliness was, at least partly, an act. He was aware of what he was doing, and did it intentionally. For example, “In his prayer (where he was, of course, to remember Sir Thomas Pope, our founder, and the Lady Elizabeth, his wife, deceased) he would many times make a willful mistake, and then say ‘Thomas Pope, our confounder’, but then presently recall himself.”

For a final detail, “he dragged with one foot a little, by which he gave warning of his coming, like a rattlesnake. Will Egerton, a good wit and mimic, would go so like him that sometimes he would make the whole chapel rise up imagining he had been entering in.”

If you make an NPC inspired by Kettell, also prepare in advance some silly things he might say: asides, non-sequiturs, and funny-sounding words. It can be hard to extemporize such things on the spot. Keep these words vague and generic so you can drop them in wherever.

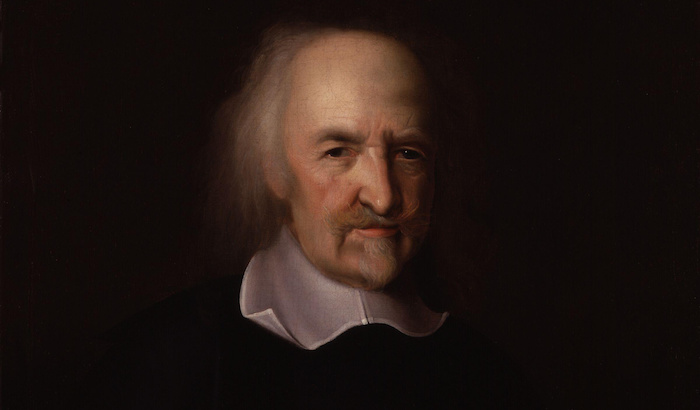

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was a political philosopher best known today for his work Leviathan, which argues that humans cooperate to build societies out of mutual self-interest and are best ruled by a strong monarch. His mother went into labor with him when she heard the news that the Spanish armada was coming to invade England. His father was a poorly-educated churchman more interested in gambling than Jesus. Hobbes’ father killed a parson in a dispute, fled, and died in obscurity.

Hobbes fled England during the Civil Wars and wrote Leviathan in comfortable exile in France. It was not wise to compose political philosophy in England while Englishmen murdered one another over that exact point. After the restoration of the monarchy, he found a home (but few friends) at the court of King Charles II. The king called Hobbes ‘the bear’ because the other courtiers so loved making provocative statements to infuriate him. When Hobbes would come into the room, Charles would mutter, “Here comes the bear to be baited.”

Like many a modern keyboard warrior, Hobbes was a ferocious arguer but a coward in real life. Folks joked the same fear that triggered his birth infected his mind permanently. There were persistent rumors he wouldn’t sleep without a candle burning – not for fear of ghosts or goblins, but burglars.

Hobbes was, perhaps unsurprisingly, religiously unconventional. He was an Anglican by default, but largely because he couldn’t find a better religion. He inveighed “against the cruelty of Moses for putting so many thousands to the sword for bowing to the golden calf.” After the restoration of the monarchy, the bishops in Parliament made a motion to burn him for heresy. Hobbes immediately destroyed several religiously suspect papers of his, including a poem about the encroachment of the clergy upon civil power.

Despite his enemies, Hobbes lived to old age, where he penned a wonderful poem about finding love in his dotage:

Tho’ I am past ninety, and too old

T’ expect preferment in the Court of Cupid,

And many Winters made me ev’n so cold

I am become almost all over stupid,

Yet I can love and have a Mistress too,

As fair as can be and as wise as fair;

And yet not proud, nor anything will do

To make me of her favor to despair.

To tell you who she is were very bold;

But if i’ th’ Character your Self you find

Think not the man a Fool tho’ he be old

Who loves in Body fair, a fairer mind

An NPC based on Hobbes might be pitiable: a brilliant mind beset by those who do not appreciate it, yearning for the happiness he may find only in later life – long after your campaign is already ended. Still, he’s got lots of conflict built in: hated by politicians, clergymen, metaphorical bear-baiters, and perhaps even the children of the parson his father murdered. Particularly devious courtiers may even pretend to befriend this affection-starved misanthrope so that they can influence his writings to their political gain. If your players are sympathetic to your Hobbes-analogue NPC, they may try to extricate him from the unfortunate web he’s caught himself in.

Francis Potter (1594-1678) was a theologian and mechanical inventor. He was a sickly fellow with a habit of hyperventilating. As a theologian, he was best known for his book The Number of the Beast, an analysis of the mathematical properties of the number 666 – though one that, according to Aubrey, sometimes fudges the math a little in order to make the book more compelling. He was an Anglican and had a great fear of the Pope. He “oftentimes dreamed he was at Rome and, being in fright that he should be seized and brought before the Pope, did wake with the fear.”

Potter suspected he could cure diseases by transfusing blood from one man to another. Apparently he got the idea from Ovid’s story of Jason and Medea, which is weird since it’s an obvious work of fiction. Apparently, Potter once told Aubrey about his blood-swapping idea and then ten years later roped the rumor-monger into helping him try it out on a hen. The hen died. Aubrey then sent Potter a surgeon’s lancet as a gift, which suggests they might have been trying the experiment with a kitchen knife or some other non-surgical instrument. Potter later slipped into irrelevance and was forgotten.

An NPC based on Potter is a weirdo loser. This is a guy who shows up on your doorstep at two in the morning with a chef’s knife and a live chicken asking your help to try a medical technique he saw on Game of Thrones. He’s terrified of the Pope (or your setting’s equivalent) and never lets a little thing like facts stand in the way of his scholastic imaginings.

Continuing with the theme of blood, William Harvey (1578-1657) was an anatomist and doctor who developed the idea that blood circulates through the body, pumped by the heart, and demonstrated it experimentally. Aubrey saw him at Trinity College when Harvey visited George Bathurst, who was hatching chickens from eggs that had a window of shell removed so you could watch the embryo develop. Harvey did a lot of experiments in that vein. He dissected frogs, toads, and other animals, and he wrote a book about insects. All these papers and observations were lost when his lodgings were plundered by Parliamentarians at the start of the Civil Wars; Harvey was on the side of King Charles. For all that he was a great anatomist, he was apparently a lousy doctor. Says Aubrey, “I knew several practicers in London that would not have given three pence for one of his treatments, and that a man could hardly tell by one of his prescriptions what he did aim at.”

I regret to inform you that Harvey was definitely a vampire. We already mentioned his interest in blood and his affinity for frogs and toads, but he also “did delight to be in the dark, and told me he could then best contemplate. He had a house heretofore at Combe, in Surrey, a good air and prospect, where he had caves made in the earth.” He was also violent: “…in his young days [he] wore a dagger (as the fashion then was), but this doctor would be apt to draw out his dagger upon every slight occasion.”

An NPC based on Harvey is clearly a vampire. The secret to uncovering the fact (or the way to defeat him) lies in his plundered works. The soldiers who looted your Harvey-analogue’s lodgings likely didn’t know what they had and sold the papers to the nearest bookseller. That bookseller (or whoever she resold the books to) is sitting on secrets Harvey would be desperate to recover.

Walter Warner (died 1640) was a lesser mind who felt he had discovered the circulation of the blood before Harvey and was denied credit. That’s untrue, of course. He made some basic observations, filtered them through the conventional theory of the time, and never published anything that would back up his claim. That didn’t stop him from being very bitter. An NPC based on Warner could be a memorable ally in the party’s war agains the vampire Harvey.

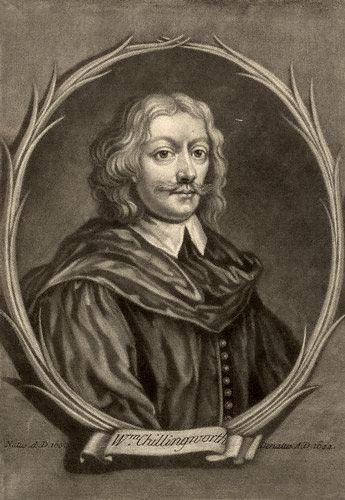

William Chillingworth (1602-1644) was a theologian at Trinity College. His godfather was William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury and ferocious Royalist partisan. Chillingworth acted within the college as an informant, reporting on scholars and students who were insufficiently loyal to the crown. A schoolmaster wrote a letter calling King James I and his son “the old fool and the young one” and Chillingworth ratted him out to Laud. The schoolmaster was arrested and might have suffered a terrible punishment had cooler heads not prevailed. An NPC based on Chillingworth is similarly an informant. His ‘handler’ being his godfather is perfect; it’s a close enough relationship that your players will buy it, but it’s not so close that anyone will watch their mouth around the NPC as they would if the politically-connected handler were, say, his mother.

Lucius Cary (1610-1643) was Viscount Falkland and a member of Parliament who sided with the King and died in the Civil Wars. His mother was a devout Catholic. In her attempts to get her son to join her unfashionable, a-little-bit-treasonous religion, she encouraged him to look at many religions to see that Anglicanism wasn’t the only option. Unfortunately for her, he encountered Socinianism, a strain of Christianity popular then in Poland that denied the Trinity. He was quite taken with it and became the first Socinian in England. As far as NPCs go, this isn’t enough in and of itself, but being the only member of a strange foreign interpretation of the region’s normal religion is a fun trait to apply to a scholarly NPC.

Thomas Street (1622-1689) was an astronomer and clerk. After his death, two of his friends confided in Aubrey that Street had secretly discovered how to determine longitude by observing the moon, but had not written it down. During this period longitude could not be determined with accuracy, which was a serious problem for ships at sea. Lunar observations were a contender as a solution, though they were ultimately beaten out by accurate clocks. Had Street actually developed such a system, he could have made a lot of money from it. In truth, he probably had no more solved the longitude problem than William Harvey was actually a vampire, but an NPC based on Street might have! Perhaps he hasn’t revealed his system because a foreign power has secretly offered him a fortune for it, and he’s trying to find a way out of the country.

About the source, Aubrey’s Brief Lives

John Aubrey (1626-1697) was an English country gentleman. He had the ambition to write a collection of biographies of the great Britons of his era: roughly the 1600s, though he included many men who died old in the early 1600s, and so we think of as being more Elizabethan in character. Aubrey compiled a great collection of salacious gossip – mostly obtained at drinking parties – but he never actually wrote his book. Instead, he left behind a collection of notes and letters full of the sorts of details that seldom make it into sober scholarship. The longer and more interesting contents of these papers have been often published under the title Aubrey’s Brief Lives.

A good example of the content of Aubrey’s Lives is this quote about Edward de Vere, which you may be familiar with: “This Earl of Oxford, making of his low obeisance to Queen Elizabeth, happened to let a fart, at which he was so abashed and ashamed that he went to travel for seven years. On his return, the Queen welcomed him home and said, ‘My lord, I had forgotten the fart.’”

It’s amazing seeing 17th century Britain – a wild period full of civil wars, a regicide, a theocratic dictatorship, the restoration of the monarchy, and so much gilt and ostentation – through the eyes of one particular human with all his idiosyncrasies. Newton may be found in Aubrey, but only as an idle mention in other people’s stories. Shakespeare is in Aubrey, but only his comedies are mentioned – and only A Midsummer Night’s Dream by name. Aubrey seems less interested in Shakespeare’s literary work than in his friendship with Ben Johnson. By contrast, Aubrey presents an endless parade of doctors of divinity, breathlessly describing their interchangeable virtues.

Women appear rarely, and usually only in reference to their beauty or sexual proclivities. A good example is the entry for Eleanor Radcliffe, the Countess of Sussex: “A great and sad example of the power of lust and slavery of it. She was as great a beauty as any in England, and had a good wit. After her lord’s death (he was jealous) she sends for one (formerly her footman) and makes him groom of the chamber. He had the pox and she knew it; a damnable Scot. He was not very handsome, but his body of an exquisite shape. His nostrils were stuffed and borne out with corks in which were quills to breathe through. About 1666 this countess died of the Pox.”