Shanty Hunters, my upcoming RPG about collecting magical sea shanties in 1880, goes live on Kickstarter in November. This week on the blog, I’d like to offer a sneak peek: an excerpt about the nature of the sea and another historical shanty from the shanty songbook. Last month, we looked at the book’s first five pages. To learn more about Shanty Hunters and be notified when the Kickstarter launches, follow this link!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

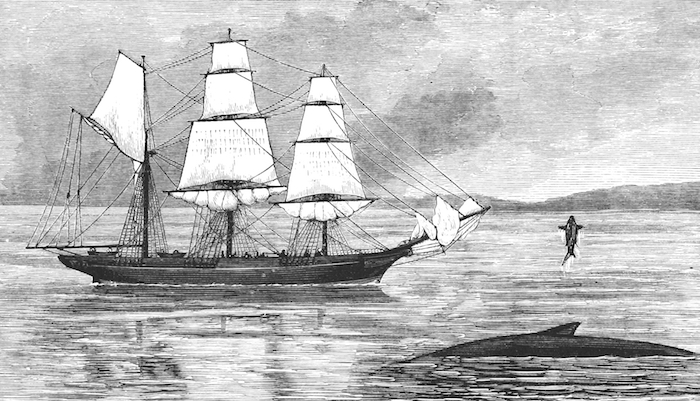

The sea is a living thing, simultaneously inconstant and unchanging. Its very texture differs from place to place. The South China Sea is glassy and clear like a polished gemstone, with a blue so deep you’d think it should stain the hull. The Persian Gulf sparkles with ten thousand sharp pinpricks, like television static. Manila Bay is dark and blood-warm. The Atlantic looks hard as slate.

To be on a ship far out at sea is to stand at the center of a vast circle. If the day is calm, the horizon is unbroken, the surface bare as an egg. In the direction of the sun, it is a gleaming mirror, so bright it hurts to look at. If the weather is foul, there is no horizon. The dark gray of the sea blends into the light gray of the sky. Even if the waves are small, the ocean seems to rise around you, tower over you. You are a guest in her home, afloat only because she hasn’t noticed you. She’s too vast to see something so small.

At sea outside of a storm, the general experience is one of openness. There are no trees or hills to block the horizon, no buildings to rest your back against. Even the space below you is open, with countless fathoms of void between you and the seafloor. You’re just… exposed. The smell is of musty clothes and hemp rope, not the rot and salt landsmen associate with the sea. That is the smell of the seashore, and a sailor interprets it as the smell of land, which he may detect before the lookout spies it. The rocking of the ship is irregular. She rolls side to side in time with the waves and may rock fore and aft depending on her course relative to them. But how long it takes to complete each roll, how far she rolls, and how long she stays rolled varies with each swing of the pendulum.

This chapter is intentionally incomplete. Life at sea is just as complicated, intricate, and nuanced as life ashore. To keep things manageable, there is much I’ve omitted; I tried merely to reach a level of detail useful for GMs designing adventures. If you want to get further into the weeds, I recommend the Text-Book of Seamanship: The Equipping and Handling of Vessels Under Sail or Steam by Commodore S.B. Luce (1891), The American Practical Navigator by Nathaniel Bowditch (1802), and Two Years Before the Mast by Richard Henry Dana Jr. (1840).

Waves

Waves at sea are not the breaking crashers you see at the beach. Those are the twitching corpses of what once was; these are the animal whole, vibrant, possessed of a will. Where the winds are regular, the waves are swells. These undulating sine waves slide in the direction of the breeze, perfectly parallel but imperfectly regular. They are all slightly different sizes, slightly unevenly spaced. No two animals are ever quite identical. If the winds do not shift, the same swells may cross an entire ocean. If the wind is strong and blows over hundreds of miles, the swells grow as they travel. In monsoon season, a two-inch wave off Somalia grows dozens of feet before it smashes into the Indian shoreline.

If the wind is not regular enough to produce swells, it produces waves. The same water can have patterns of waves moving in multiple directions simultaneously. Each pattern is carried along by inertia lent to it by far-off winds it no longer feels. When two such waves pass through each other, their heights (and depths) combine. Thus, a bottle floating in a chaotic sea may float steady for a half-dozen seconds as the crest of this wave temporarily cancels out the trough of that wave, then suddenly drop as two or more troughs intersect underneath it. Looking out on such a messy scene, the surface seems to pop every few seconds in an unpredictable direction, as several wave crests unexpectedly combine to spike a spot upwards, creating an effect akin to the geyser created by throwing a stone in a pond.

Upon each wave and swell there are often wavelets. Wavelets are miniature crests and troughs, all moving in their own directions, created by brief shifts in the wind too small to impact the waves or swells. They lend a knapped texture to the features they so briefly transit: shallow divots separated by ever-shifting sharp curved ridges, like the surface of natural obsidian or worked flint. In a breeze or stronger, these wavelets may form whitecaps. These are not the foamy crests of breaking waves at the beach, but are the effect of the wind ripping the surface off an errant wavelet and whipping it into foam.

<In the actual book, there’s a section here on wind, but we will skip over it!>

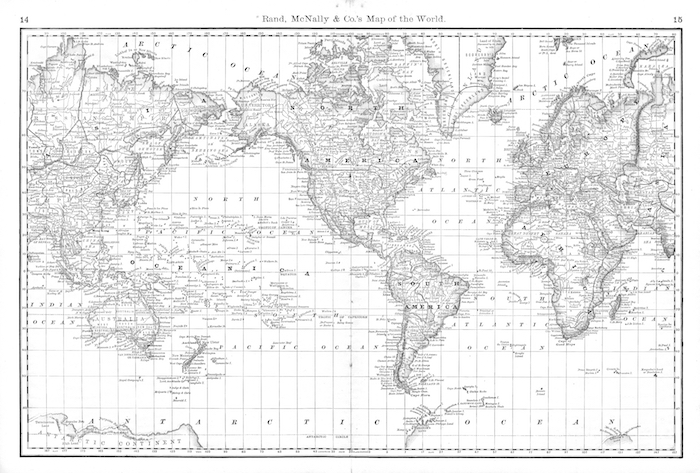

Important Regions

These stretches of sea are important to the sailing profession. Your PCs will likely pass through them. Lean on these areas’ unique characteristics to make these voyages feel special.

The Trades

The seas within thirty degrees of the equator are dominated by the trade winds (or ‘trades’). North of the equator, the trades blow from the northeast. South of the equator, they blow from the southeast. For a few degrees on either side of the equator, they get complicated (see the next section). The trades blow steady and unchanging. They shift in neither direction nor intensity. You may sail for three weeks in the trades and not shift your sails once.

The Line

The equator (or ‘Line’) is important to sailors for two reasons. First, the winds are unpredictable here. The Line is beset by thunderstorms, but also by days or weeks of calm. Without wind, sailing ships cannot move. Crossing the Line can thus be a frustrating affair. Brief squalls are also common here. The horizon is often dotted with gray mushrooms: a pillar of rain a quarter-mile across, topped by a dark cloud.

The second reason is the Crossing the Line ceremony. This is a maritime baptism for sailors who have never crossed the equator before. These sailors, called pollywogs, must undergo an initiation carried out by the sailors who have crossed the Line before, called shellbacks. Some of the shellbacks assemble costumes from whatever castoffs they can find and parade about as King Neptune, Queen Amphitrite, the herald Davy Jones, and other members of King Neptune’s court. King Neptune feigns outrage that pollywogs have been permitted in his kingdom and orders the shellbacks to punish them. The shellbacks then haze the hell out of the pollywogs, spraying them with water from the pumps, beating them with hoses, performing pranks, and forcing them into various indignities. At the end of the ceremony, the pollywogs are baptized in salt water and become trusty shellbacks.

The Horse Latitudes

The Horse Latitudes fall at about thirty degrees north and south of the equator. Days or weeks of calm are common here. The name supposedly comes from the European colonization of the Americas, when ships would be becalmed in the Atlantic for so long that, to conserve drinking water, the crew would force the colonists’ horses into the ocean to drown.

The Roaring Forties

Once you hit about forty degrees north or south latitude, the winds pick up again – but this time, they blow out of the west. The Roaring Forties are noteworthy in the northern hemisphere, but truly strong in the southern hemisphere. Here, the winds blow in a band all the way around the world with nothing to slow them except the tip of South America. They grow stronger as you go farther south, forming the Furious Fifties and the Shrieking Sixties. Ships use the Roaring Forties as a superhighway between Australia and Europe. Sail south from Europe to the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa, pick up the Roaring Forties, and rocket due east all the way to Australia. To come home, keep sailing east around Cape Horn in South America, then leave the Roaring Forties to sail north back to Europe.

Cape Horn

Cape Horn, also called ‘Cape Stiff’ or just ‘the Horn’, is the southern tip of South America. Rounding the Horn is the hardest task sailing ships regularly undergo. Cape Horn is solidly in the Furious Fifties and only six hundred miles from Antarctica. It’s plagued by sudden storms, high winds, huge waves, and sleet even in summer (which is, of course, in January). Expect snow on the deck, ice in the rigging, and the hardest winds of your voyage arriving out of absolutely nowhere, prompting all hands to race aloft to shorten sail. In winter, the storms grow worse still. The whole ship grows so icebound that you cannot tie a knot in the frozen ropes, while the sails grow as hard and inflexible as sheet iron. In any season, the approach to Cape Horn can take weeks as you fight your way south through the Roaring Forties. You may go a month barely able to sleep through a watch. As soon as you nod off, a storm strikes the ship without warning and all hands are summoned on deck to reef and furl. If the Line is where sailors are baptized, Cape Horn is where they are tempered.

New York Girls

Suggested cover: Oh You New York Girls by The Fisherman’s Friends on the album Sole Mates (2018). For a lively, brassy version, see New York Girls by Bellowhead.

Shanghaid(1) in San Francisco,

We fetched up in Bombay

They set us afloat in an old lease boat

That steered like a bale of hay

Chorus:

Then away, you Santee

My dear Annie!

Oh, you New York girls

Can’t you dance the polka?

We panted in the tropics

While the pitch boiled up on deck

We’ve saved our hides little else besides

From an ice-cold North Sea wreck

Chorus

We know the track to Auckland

And the light of Kinsale Head(2)

And we crept close-hauled while the leadman called

The depth of the Channel bed(3)

Sing Time For Us to Leave Her(4)

Sing Bound for the Rio Grande(5)

When the tug turns back, we’ll follow her track

For a last long look at land

And when the purple disappears

And only the blue is seen

That’ll take our bones to Davy Jones

And our souls to Fiddler’s Green

1: Getting a sailor drunk, then kidnapping him and bringing him aboard your ship. By the time he wakes up, you’re already at sea. The practice is illegal, but some unscrupulous captains still practice it to fill out their crews.

2: A lighthouse in southern Ireland.

3: The English Channel is foggy, and parts of it are lined with treacherous islands and rocks. When visibility is bad, it’s advisable to move slowly while constantly ‘sounding’ the water depth with a lead weight on the end of a line. Otherwise, you may not notice the water growing suddenly shallow until you’re already upon the rocks. Sailing ‘close hauled’ is sailing in a direction near to the origin of the wind.

4: The traditional final shanty of the voyage, in which the crew can – for the first and only time all trip – openly complain about the bad working conditions they’ve endured.

5: An outward-bound anchor shanty.