Shen Fu and Chen Yu were a married couple who lived in China in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Their relationship was remarkable in many ways, not least because they were able to marry for love. Nonetheless, their lives were not easy. Chen Yu and her in-laws were like oil and water. The complications this created for the loving couple make amazing content for a roleplaying game. You probably can’t build an entire adventure out of them, but as individual incidents, these disputes are wonderful for throwing into an already-contentious situation just to make the players squirm. Right when you’re about to confront the mob boss, your father threatens to have your spouse arrested – what do you do now?

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

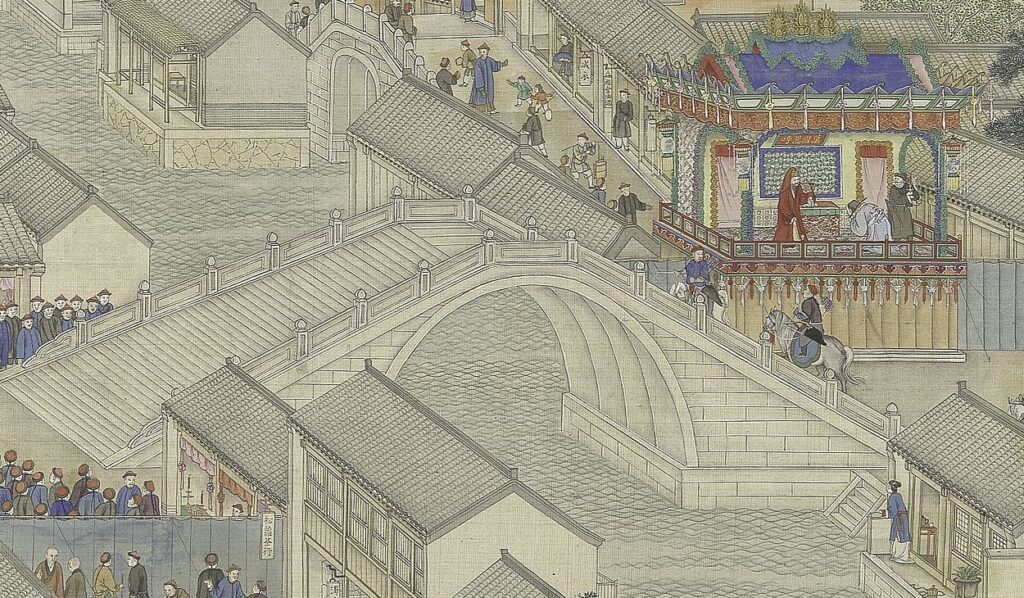

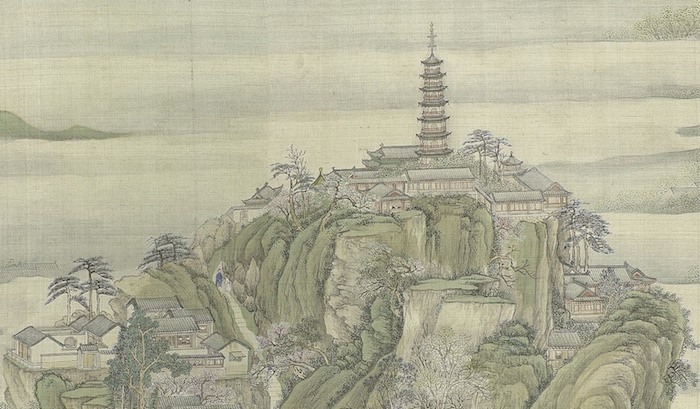

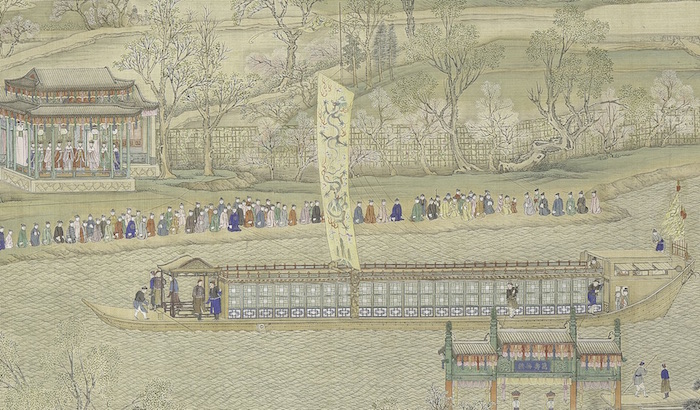

Shen Fu was born in 1763 in Suzhou, near Shanghai. His father was a scholar-gentleman and a minor government official. Chen Yu was born nearby, though her family was of lower station. Shen Fu was able to convince his parents to arrange a marriage for him with Chen Yu, even though she was a commoner. Marrying for love was unusual for gentlemen. But Shen Fu and Chen Yu were crazy about each other from the start, and that passion never waned. Shen Fu’s memoirs, Six Records from a Floating Life, are full of heartwarming passages describing the couple’s enduring romance and friendship. As a newly married man myself, the memoirs would be an inspiration, save for Chen Yu’s in-laws hating her and her dying at age 40.

The first serious incident with Chen Yu’s in-laws came about because she was literate. It was not unheard of for a scholar-gentleman’s wife to be able to read and write, but Chen Yu had a particularly keen grasp of poetry and literature. In 1785, Shen Fu was working for his father at a far-off office. Chen Yu was back at home with Shen Fu’s mother and siblings. Chen Yu sent her husband regular letters, and his father suggested (by letter) she might write down letters for Shen Fu’s mother, who was presumably illiterate. But there was some gossip, and the mother suspected Chen Yu of slipping something improper into one of the mother’s letters. Shen Fu’s mother stopped asking Chen Yu to write for her.

When Shen Fu’s father noticed the letters from his wife were no longer written in the handwriting of his daughter-in-law, he grew furious. “Does your wife think she’s too good to write letters for mine?” Chen Yu begged Shen Fu not to tell him the truth. She’d rather her father-in-law (with whom she spoke rarely) be angry with her than her mother-in-law, whom she had to see daily. So even though Chen Yu was in the right, her in-laws’ ire deepened.

The next incident came in 1792. Shen Fu’s father was away on work with another son, Chi-tang. Shen Fu went out to visit them. While he was there, he got a letter from Chen Yu, explaining that a neighbor was bothering her. Apparently, Chi-tang had borrowed money from the neighbor and Chen Yu agreed to cosign the loan; it was the sisterly thing to do. Now Chi-tang was far away and hadn’t repaid the loan, and the neighbor was hassling Chen Yu for the money. Shen Fu advised his wife to let Chi-tang handle it. It was his loan. Let it be his problem.

Chen Yu sent another letter in response, but her husband was already on his way home. When the letter arrived, Shen Fu was gone, so his father opened it. He asked Chi-tang about the loan the letter referenced, and Chi-tang denied all knowledge. Also in the letter, Chen Yu referred to her in-laws as “your mother” and “the old man”. That was just fine for a conversation between two spouses who were deep and trusting friends, but wholly inappropriate language to use in front of the in-laws; there were special terms of respect she should have used.

Once again, Shen Fu’s father was furious. His interpretation of the situation was that his daughter-in-law lacked filial piety, which was not just sinful, but also criminal! Furthermore, she’d borrowed money from a neighbor and was blaming her brother-in-law, Chi-tang, for her actions. He ordered Shen Fu and Chen Yu to leave the family estate. He was actually being lenient – he could have ordered them to divorce. Shen Fu and Chen Yu had no money, so they had to go live with friends. It would be two years before Shen Fu’s father realized what had happened and let the couple come back home.

The third and final incident built slowly. In 1795, the couple met Han-yuan, a professional concubine. She was beautiful, charming, and they were both much taken with her. It would be good for Shen Fu’s career if he had a concubine, so Chen Yu set about adding Han-yuan to their household, though it was not clear how the penniless couple could maintain her in the lifestyle to which she was accustomed. Han-yuan, as it turned out, was just as fond of the couple as they were of her, and was willing to lower her standards to be with them – both of them, as Chen Yu made quite clear with a reference to a century-old play about a wife who falls in love with a girl and arranges for her to become her husband’s concubine, so the wife and the girl can be together.

You’ll be shocked to learn that Shen Fu’s parents disapproved of the situation. They didn’t mind that Chen Yu and Han-yuan were lovers – female homosexuality was perfectly acceptable at the time. Nor did they mind that their son was part of a ‘thruple’, which was also perfectly fine. Their objection was that Chen Yu and Han-yuan were emotionally intimate, that their daughter-in-law had ‘pledged sisterhood’ with ‘a sing-song girl’. The scorn between Chen Yu and her in-laws deepened daily.

But time marches on, and Han-yuan caught the eye of an influential man. He offered her a thousand ounces of gold and to take care of her mother, and Han-yuan left with him. She was a professional; whatever her private feelings may have been, Han-yuan couldn’t turn down a career move like that. Chen Yu was badly affected by her lover’s departure and fell ill. She and her in-laws did not make up.

The next step in the incident came in 1800 and involved another debt. Shen Fu agreed to cosign a loan taken out by a friend, but the friend skipped town. The money-lender started coming by the family estate to demand repayment. Complicating matters, the money-lender was from western China – perhaps one of the Tibetan or Mongol tribes. For a member of an ethnic minority to be making a scene outside the estate of a Han (ethnic Chinese) scholar-gentleman family was shameful. Shen Fu’s father was livid.

Just then, a messenger arrived for Chen Yu. He was sent by one of Chen Yu’s old friends to express condolences for her illness. But Shen Fu’s father didn’t wait to hear what the message was. He assumed straightaway that the messenger was from the concubine Han-yuan and exploded. He threatened to have Shen Fu executed for lack of filial piety and gave his son and daughter-in-law three days to vacate the family estate. The couple couldn’t afford to take their children with them, so they arranged a hasty marriage for their daughter, found a master for their son to apprentice to, and fled. Chen Yu never saw her children again; she fell sick and died three years later.

If you’re playing a romance- and scandal-centered game like Good Society: A Jane Austen RPG, you can use incidents from the lives of Shen Fu and Chen Yu pretty much as-written to create scenarios. But even if you’re playing something more conventional, these three incidents are amazing inspiration for ways to complicate your PCs’ lives.

I often find myself in a situation where I’m staring at my gaming notes saying “This is all great stuff, but it’s only going to take an hour to run. It’s too straightforward. I need to find a way to complicate this.” And that’s what these three incidents are: they’re ways to complicate some other scenario. Are you neck-deep in negotiations with the vampire queen? Cool, simultaneous to that, one of your PCs has to deal with the fact that his spouse cosigned a loan they can’t repay. And to tie the vampire queen A-plot in with the loan repayment B-plot, have the moneylender be the vampire queen’s best friend.

It’s something of a cliché that PCs often spring from holes in the ground without family or attachment. What’s great about these three incidents is they don’t negate that. Instead of the NPC based on Shen Fu or Chen Yu being a PC’s wife, the NPC can be their sister or childhood best friend. Instead of the dispute being with Shen Fu’s parents, it can be with his boss at work or his on-again off-again boyfriend. Most importantly, none of these NPCs need to have been introduced ahead of time. Sure, it’s better if they’ve appeared in a session or two before this, and it’s probably a good idea to run a scene showcasing this new NPC, but if you ask your group whether anyone’s character might have a spouse or sibling or parent they’ve never mentioned, someone will volunteer. Then boom! Improvise that NPC, give them a spotlight scene so the players can meet them and care about them, and then complicate their lives with a dispute based on one of the three incidents above.

–

Source: Six Records from a Floating Life by Shen Fu (ca. 1808), translated by Leonard Pratt and Chiang Su-hui (1983)