The 17th through early 19th centuries saw a huge demand for forced labor on the plantations of the New World. Enslaved people were dragged from West Africa by the millions, and many men grew rich trading in lives and suffering. These men are natural villains, perfect for the gaming table. Let’s look at three.

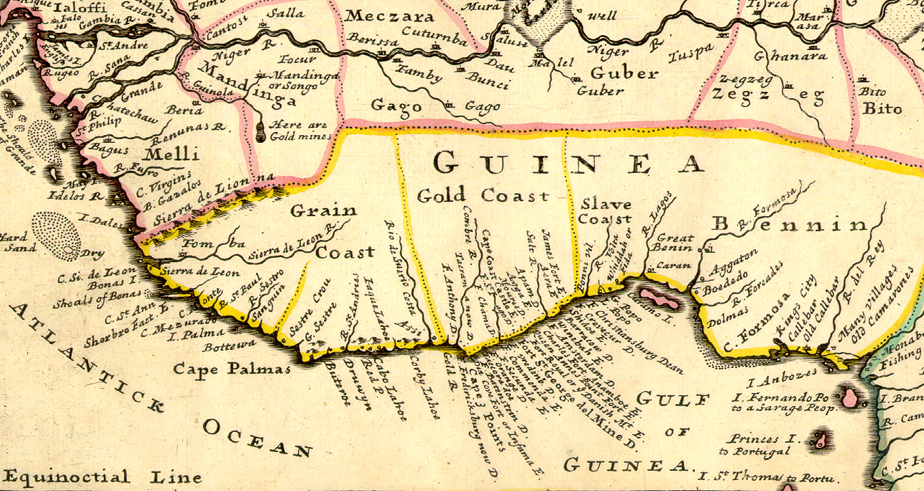

The Formosa River abuts to the western edge of the Niger Delta, in modern Nigeria. In the 1760s, it was part of the Kingdom of Benin, which should not be confused with the modern-day Republic of Benin. Quoting here from James Stanfield’s Observations On A Voyage To The Coast Of Africa:

“Among the islands and creeks that are numerous about the mouth of the River Formosa, there was also a kind of pirate admiral, distinguished by the name and title of Captain Lemma-Lemma. This personage had a powerful fleet of war canoes, with which he made descents on all parts of the unprotected coast; he paid no taxes, but declared himself independent of the king of Benin, whose subjects he carried off for trade at every opportunity. To this man, and his exertions, we were a good deal indebted for our cargo.”

The depredations of Captain Lemma-Lemma (and those like him) left much of coastal Benin depopulated. His effectiveness was due in part to his war canoes. He had at least ten in his fleet, and some were large enough to carry eight swivel guns (small cannons). Going up against a war canoe in a tight, twisting creek could be an immensely fun combat encounter.

Henry Tucker was a powerful mixed-race slave trader headquartered just south of York Island in Sierra Leone. He was the head of a large family of slave traders descended from a British Royal African Company agent and his African wife. In the 1750s, Tucker was a powerful man in the ‘African trade’. He was wealthy, much richer than the local kings, and lived in a European style in a town of his own construction. The captains of European slave ships considered him an honest trader, and they wined and dined him aboard their ships. Nonetheless, they quietly resented his strong bargaining position, which cut into their profits. Tucker’s relationships with the locals were, unsurprisingly, less favorable. He made sure that almost everyone on his stretch of the coast owed him money. The terms of their debt let him force them into slavery on a whim. Consequently, Tucker never lacked for enslaved ‘cargo’ to sell.

Henry Tucker’s nemesis was his less-successful older brother, Peter Tucker. Henry supported Peter financially, but Peter was jealous. He tried to have Henry killed and conspired with local kings to cut off trade with him. At your table, Peter might be an ally in the party’s fight against the slaver lord. So might European slaver captains, who believe they’ll get a better deal if they don’t have to treat with a powerful middleman. Of course, if the PCs use these people to get close to Henry, they’ll be indebted to men who, while not as villainous as Henry Tucker, are monsters in their own right. Peter and the captains may return later in the campaign to call in a favor. Worse, with Henry out of the way, they’ll be stronger than before. The PCs may not be able to say ‘no’.

John Kabes was a merchant prince along the Gold Coast from 1683-1722. Like Tucker, Kabes was a middleman, but he wielded considerably more power. Kabes built up a network of relationships in the African state of Eguafo, in the Gold Coast (modern-day Ghana). He maneuvered himself into a situation where he was the only buyer the locals would sell to, and therefore the only seller the Europeans could buy from. Multiple European slave traders were quoted saying that without Kabes’ blessing, profitable slave trading with Eguafo was impossible.

Kabes worked for a variety of colonial powers, but he was no man’s servant. He built his own fortress, Fort Komenda, despite the opposition of a Dutch fort within cannon range. He even obtained his own stool, a symbol of chieftainship, sovereignty, and political power among the local Akan people. With his fortress, political connections, and iron grip on the most profitable industry in the area, a villain based on John Kabes would be a formidable opponent.

Image credit: The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis, released under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Slavers are inherently monstrous, and stopping them is an obvious plot hook. They also work in almost any setting: anywhere with a large, vulnerable population and a wealthy outside power with a ferocious need for labor.

If war canoes, commodore’d by an NPC based on Captain Lemma-Lemma show up in your PCs’ homeland, the party will probably ride out to stop them. If war canoes don’t work for your setting, consider armed cargo helicopters, dinosaurs with howdahs, or science fiction gunships. Hunting the flagship war canoe through the twisting streams (or dense forest paths, or what-have-you) could be a really fun session. Then, with the Lemma-Lemma-analogue defeated, the PCs hear of the villain he was selling their friends and neighbors to. I recommend combining Tucker and Kabes to some extent. Kabes has a fort and strong local connections. Tucker has debt relationships everywhere and some nemeses. Both are cruel and tyrannical. Why not give your slaver mastermind all these traits?

But what about the greatest villains in the trade: the distant European merchants who moved and paid for the enslaved? Next week, we’ll look at how British abolitionists spied on the slave trade to collect the information they needed to shut it down!

–

Sources:

The Slave Ship: A Human History by Marcus Rediker

A History of Sierra Leone by C. Magbaily Fyle

The Guinea Voyage: Observations On a Voyage To The Coast of Africa by James Field Stanfield