The British theft of tea from China in 1848-1851 ranks as one of the greatest acts of industrial espionage in history. It also makes a fresh, original RPG adventure. It’s not likely your players will have ever before stolen live plants from a foreign land!

In the mid-19th century, England made enormous sums of money buying tea from China and reselling it in Europe. But the East India Trading Company had eyes on even greater profits. If the company could grow tea in British-occupied India, they’d cut out the Chinese and balloon their profits. So the Brits set out to steal live tea plants to replant in India. Their man was a Scottish horticulturalist named Robert Fortune.

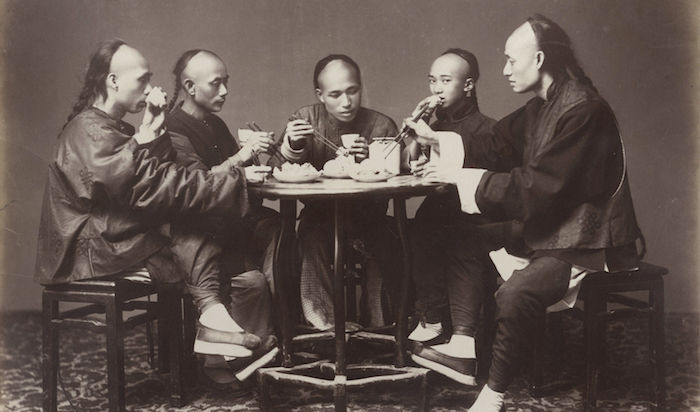

Westerners were not permitted outside their trading enclaves in coastal China. Fortune would have to go in disguise. He bought clothes appropriate for a mandarin (Imperial official), and had a long, traditional ‘tail’ (queue) stitched into the hair on the back of his head. Fortune’s cover story for why he was a foot taller than everyone else and had such bizarre facial features was that he was Chinese, but from a distant province beyond the Great Wall. Few Chinese folks outside the trading entrepôts had ever seen a white man, so it wasn’t an unreasonable ploy. It was a sort of 19th-century equivalent of “My girlfriend goes to another school; you wouldn’t know her.”

To help him pass as Chinese, Fortune leaned heavily on his hired servant, Sing Hoo. The man’s most important role was to translate for Fortune, who learned Chinese in an earlier voyage to China, but not the right dialect for their destination. Sing Hoo also hired the porters they’d rely on and helped the Scotsman navigate Chinese cultural practices. Sing Hoo was a remarkable figure. He’d once worked for a high-ranking official at the Imperial court. As a parting gift, Sing Hoo’s former master gave him a triangular flag that signaled the servant had imperial protection. When Sing Hoo showed his flag, threats and insults from strangers disappeared, replaced with hasty apologies. The servant was well aware of Fortune’s scheme and knew that the Scotsman needed his servant far more than the inverse. Consequently, Sing Hoo refused to do work he felt was below his station, and regularly skimmed off the money Fortune gave him for expenses.

Fortune, Sing Hoo, and their porters had a hard overland journey to the heart of Chinese black tea production in Fujian province. Along the way, Fortune stopped often to collect live plants unknown to Western horticulture. He transported them the same way he would the tea plants: in Wardian cases.

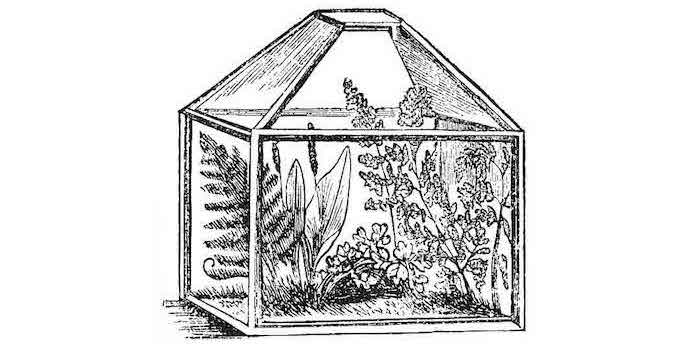

The Wardian case was the predecessor to the modern terrarium. It was a sealed glass box in which plants could be placed for protection. With no way for air to get in or out, the cases developed miniature water cycles. The plants cycled oxygen and carbon dioxide back and forth in patterns of photosynthesis and respiration. As long as the cases got regular sunlight, plants could live in them for years. Were the case opened and re-sealed, though, mold spores usually got in and killed the plants.

The technology was new at the time, and it revolutionized plant transport. Ships are bad for plants. If kept on deck, the salt air kills them. If kept down below, the darkness does the same. The sealed Wardian case solved that problem, and made the cross-continental transport of live plants reliable.

The porters were not thrilled by Fortune’s en-route acquisitions. They were already hauling fragile boxes up and down steep mountainsides. Now they were increasingly burdened by the weight of sod and what they saw as weeds. Fortune had to flatter, bribe, and bully the porters to keep them from walking off the job.

Modified from original by author Reportzite. Released under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

At last, the travelers reached their destination: the breathtaking karst landscape of Wuyishan. To this day, it produces some of the most expensive black teas in the world. The best tea plants in Wuyishan are cuttings (clones) of three semi-mythic plants. Once upon a time, the legend goes, nine evil dragons ravaged Wuyishan. This angered a benevolent god, who turned the dragons to stone, creating the nine karst cones that still symbolize the area. So the locals wouldn’t forget his great deed, the god left behind three unusually potent tea plants. The locals grew cuttings of the plants, cloning them. Robert Fortune collected thousands of cuttings from the farms of Wuyishan, planted them in his Wardian cases, and cloned the clones.

But Fortune needed more than the plants. If stolen Indian tea was to be as good as Chinese tea, he also had to learn the cultivation practices that produced the most flavorful leaves. Here, Sing Hoo proved invaluable. The servant arranged guest quarters for them at a local monastery. Sing Hoo convincingly claimed Fortune was a powerful mandarin and should be treated as a visiting dignitary. Over the course of their stay, Sing Hoo inflated Fortune’s supposed importance bit by bit, until the Scotsman was a rich man, a feared warrior, a descendant of Genghis Khan, and an advisor to the Emperor himself.

The monks were a treasure trove of horticultural data. They were all experienced tea growers. And they had centuries of records showing which fields were most productive and why. In their enthusiasm to help the strange mandarin, the monks unknowingly betrayed the secrets of their country’s greatest tea to its greatest economic enemy.

Modified from original by author ‘rheins’. Released under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

The return trip to Shanghai was not without incident. One evening in a roadside inn, Fortune found Sing Hoo brawling with almost a dozen other guests – one against all – including their porters! Sing Hoo had his back against the wall as he kept his unarmed assailants at bay with a lit incense stick. Fortune ended the situation by brandishing a pistol and ordering everyone to break it up. Little did the cowed fighters realize the weapon was broken – it was a bluff!

It turned out Sing Hoo had promised the crowd money, then refused to pay. Fortune ordered his servant to pay up, thereby defusing the situation. It was a risky move. It publicly shamed Sing Hoo, who knew Fortune’s secret and might have exposed him to get even. That didn’t ultimately happen, but the porters were so upset, they walked off the job in the middle of the night. Fortune made Sing Hoo carry everyone’s burdens until they found new porters a few days later.

What’s great about this adventure is the premise is so different from what your players are used to, but the actual sequence of events isn’t that complicated. You already know how to run this adventure.

At your table, you’ll want to add some tense encounters on the road. In real life, the Taiping rebellion was getting started during Fortune’s theft. He never encountered these Sino-Christian rebels, but your PCs might have a run-in with a band based on them (adapted for your setting, of course). They also might encounter monsters, bandits, government patrols, or even a well-traveled merchant who recognizes your PCs as outsiders, not travelers from a distant corner of your fictional empire. If the situation devolves into combat, having to protect the fragile Wardian cases is a fun complication.

In your adventure, you’ll want to include a Sing Hoo-like NPC, but don’t make him a translator. You want your PCs to be able to speak the local language. Otherwise, the players won’t be able to roleplay much with local NPCs. Instead, have your Sing Hoo-analogue ‘merely’ help the party navigate the locals’ alien cultural practices. The PCs will still need him more than he needs them (which sets up a fun tension) without the obstacle to roleplay.

Your PCs may want to also steal the method of processing the leaves. In an earlier, ultimately unsuccessful mission to steal green tea cultivars from Anhui province, Fortune used his mandarin disguise to get a detailed tour of a green tea factory. There, he documented the process that turned raw leaves into usable green tea, a technique previously unknown to Westerners. One particularly remarkable discovery was that the Chinese manufacturers were using poisonous dyes to make their exported green teas visually greener, and therefore more appealing to Westerners. Having your PCs infiltrate a factory could be a lot of fun, especially if they discover something equally troubling.

Finally, if your campaign has a long arc, you can have some fun expanding the impact of the tea theft. In real life, the loss of tea revenue was one of many factors that ultimately brought down the Qing dynasty. At your table, a few years after the theft, the country the PCs robbed might suddenly go bankrupt. The government collapses, and everything falls apart. The PCs might learn of the disaster from an NPC who doesn’t know their role in it and idly mentions it was all because someone ruined the tea monopoly.

There’s also the option to have your PCs chasing tea spies, rather than being tea spies. It’s certainly more ethical, but it’s also an adventure where the PCs are reactive, not proactive.

Postscript:

There’s an additional facet to the tea theft that’s not relevant to turning the event into an adventure, but is too bizarre not to at least mention. The British tea trade with China was only one leg of a two-way exchange. When British merchant ships arrived in China, their holds were full of opium grown in British-occupied India. The illegal sale of Indian opium financed the British purchase of Chinese tea – and poisoned the Chinese people. The British East India Trading Company feared China was plotting to steal the opium poppy just as the Brits were plotting to steal the tea plant. Growing opium in China wouldn’t do anything to curb the deadly Chinese opium crisis, but at least the Chinese wouldn’t have to pay the British for the privilege of being poisoned. Fearing betrayal, the Company decided it would betray the Chinese first. This precipitated their hiring of Robert Fortune.

–

Source: For All the Tea in China by Sarah Rose