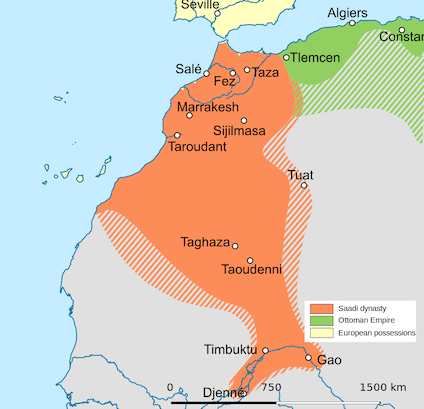

In 1590 the Saadi Sultanate in Morocco invaded the Songhai Empire in what is today Mali and Niger. The man the sultan sent to oversee the conquest and occupation did a good job, but had the temerity to question one of the sultan’s decisions and was replaced by a new guy. These two successive Saadian conquerors made convenient boogeymen for the author of one of the histories of this invasion, the Tarikh al-Sudan. The colorful stories the text gives about them make a fabulous template for a wicked governor whose king does not know of his villainy—a critical vulnerability your PCs might exploit!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Image credit: Flaspect, released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license

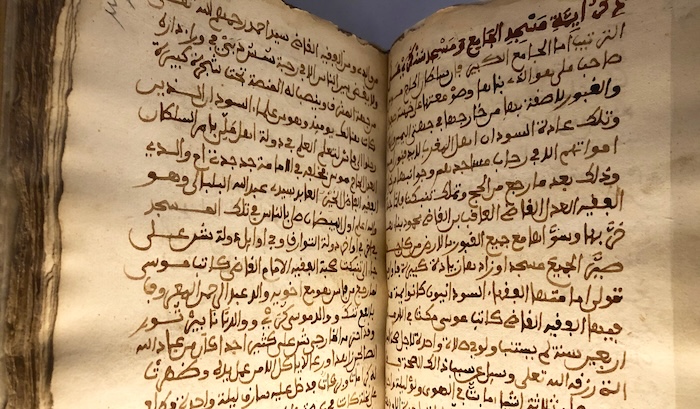

The part of the Tarkih al-Sudan that recounts the Saadian conquest of the Songhai Empire reflects a really interesting pickle on the part of the author. His sympathies clearly lie with the ethnic Songhais. But he came from a historiographical tradition that felt the downfall of dynasties and empires reflected the will of God. Worse, the author himself was a Saadian administrator in the Songhai lands. So he couldn’t describe the Saadian victory as anything other than divinely ordained, but neither could he avoid shedding tears for the Songhai loss. The way he squared the circle was to depict the Saadians—and especially their sultan—as righteous men, but to depict the two individual Saadian on-scene commanders as wicked. The author gets in his “this campaign was a tragedy” by blaming everything bad on the two commanders, thereby neatly avoiding criticizing the sultan, the Saadians in general, or the will of God Most High. We are lucky in that Moroccan histories of this invasion also survive, so the Tarikh al-Sudan’s fun contradictions aren’t as big of an obstacle as they could be.

The first leader of the Saadian conquest was born in Spain under the name Diego de Guevara. Pirates kidnapped him as a boy, forced him into slavery, and castrated him. They sold him to the Saadian sultan in Morocco. Diego grew up in the Saadian army as a eunuch soldier, adopting the name Judar and rising to the high rank of pasha. The sources describe Judar as blue-eyed and short. The Saadi Sultanate had a long dispute with the Songhai Empire on the other side of the Sahara over ownership of some salt mines on the Songhai side of the desert. When this dispute flared into violence in 1590, the sultan sent Judar Pasha to conquer the Songhai Empire. The Songhai army was much larger than Judar’s expeditionary force, but the Moroccans had muskets and the Songhais had spears. Judar took half the Songhai Empire and appointed a client emperor to rule it on his behalf.

But Judar would be undone by his pride. When he reached the Songhai capital at Gao and inspected the palace—from which the Saadian sultan expected Pasha Judar would rule—he declared it not up to his standards and sent the sultan a letter calling the palace inferior to the home of the head of the donkey-drivers in Marrakesh. When the sultan read Judar’s letter, he flew into a rage. He wrote a letter dismissing Pasha Judar and sent Judar’s replacement, Pasha Mahmud, to carry the letter to Timbuktu and the deposed commander.

Now, the author of the Tarikh al-Sudan really plays up Judar’s pride, but he’s too responsible a historian not to at least mention that Judar’s fatal letter contained something else: a peace offering. The free Songhai emperor (not the client one appointed by the Saadians) offered a huge sum of money if the Saadians would leave. Judar couldn’t accept the peace terms on the sultan’s behalf, but in his letter he encouraged the sultan to take the deal. Then Judar put the invasion on hold until he heard back from the sultan. It’s a better story—and more respectful to the Saadians—if the sultan fired Pasha Judar for complaining that an emperor’s palace was beneath him. But it’s maybe more realistic if the sultan decided he wanted a commander who would enforce his will more ruthlessly.

Pasha Mahmud, the new commander, was certainly ruthless. Indeed, the Tarikh al-Sudan author portrays Mahmud as routinely tyrannical out of expediency. He used force because it was easier than making friends. And if his actions triggered further rebellions and revolts, he could always use force to deal with those problems too. Pasha Mahmud started pissing off the locals as soon as he arrived in Timbuktu. He needed to cross the river to pursue the free Songhai emperor, but Judar hadn’t bothered to build any boats. So to get the stout timbers he needed to make good boats, Mahmud chopped down every big tree in Timbuktu and removed the structural timbers from people’s homes. Trees big enough for timber are rare in that part of the world. Even today, Timbuktu doesn’t have trees big enough to make big boats with. Some of the timbers taken from people’s houses might have been centuries old, carefully preserved for use in house after house.

Mahmud’s campaign against the free Songhai emperor ended in still more defeats for the free Songhais. The free Songhai army changed its loyalty to a new emperor, Askia Muhammad Gao, who tried again to make peace with the Saadians. When Pasha Mahmud’s army was threatened with starvation, Askia Muhammad Gao sent them millet. Mahmud swore an oath that, in gratitude, if the new free emperor came to him and swore an oath of allegiance to the sultan in Morocco, Mahmud would not harm him and the war would be over. Askia Muhammad Gao’s advisors begged him not to trust Mahmud. But Mahmud’s officers reaffirmed the Saadian’s sacred oath, and Askia Muhammad Gao met with Pasha Mahmud. During a feast of friendship, Mahmud had the new free emperor shackled. He sent Askia Muhammad Gao to the city of Gao and the palace that Pasha Judar found so repellent. There he was executed and the roof of the room where it happened was torn down upon the body to create a makeshift grave.

Meanwhile, back in Timbuktu, things were getting no better for the city folk. In late 1591, the city’s leading Islamic scholars organized a general revolt against their Saadian rulers, who retaliated by torching much of the town. Pasha Mahmud sent an officer to deal with the situation. The Tarikh al-Sudan says Mahmud gave orders that his representative was to massacre all Timbutku’s residents but that the representative facilitated a reconciliation instead. Other documents that have survived strongly suggest Mahmud’s orders were for reconciliation. This again seems consistent with the author’s attempts to lay as much blame for bad stuff on two individual people—Mahmud and Judar—and thereby avoid criticizing God’s plan or the author’s Saadian rulers.

Two years later, things bubbled to the surface again. Pasha Mahmud was away on campaign against yet another free Songhai emperor. Meanwhile, nomadic Sanhajas from the Sahara were taking advantage of all the armies being elsewhere to raid into Saadian-occupied Songhai lands. The man whom Pasha Mahmud blamed for the Timbuktu revolt two years earlier, a qadi (religious judge) named Umar, was of Sanhaja descent. Pasha Mahmud blamed Umar for a lot of his troubles and sent word the qadi had to be arrested. The governor of Timbuktu feared the consequences if he did so and found excuses. So it fell to Pasha Mahmud to enact his vengeance upon the Timbuktu scholars who’d led the revolt two years earlier. The Tarikh al-Sudan author was very fond of Umar, who came from a prestigious bloodline. He gives an elaborate story explaining how it is that everyone thinks Umar organized the revolt but actually it was this law clerk claiming he was acting on Umar’s behalf.

The first step of Mahmud’s plan to punish the scholars of Timbuktu was to announce that Saadian soldiers would be checking the homes of all the scholars for weapons. In light of the prestige of Umar’s bloodline, though, everyone who shared that bloodline would not have their houses searched. The scholars feared the searches were a pretext to steal their valuables, so they all rushed to put their most expensive possessions in the homes of Umar’s family members. After the search for weapons, Pasha Mahmud mandated that all the scholars come to the mosque to swear another oath of fealty to the sultan. When they arrived, they were arrested. Many died in custody. Some of the rest were sent in chains to Morocco. Their valuables were easy to plunder, as they’d helpfully put them all in the same place—the homes of Umar’s family members—rather than burying them in the hinterlands as the scholars might otherwise have done when they suspected foul play. Pasha Mahmud sent some of this booty to the sultan, but most of it he spread among his soldiers.

When the exiled scholars reached Morocco along with the pittance Mahmud deigned to send along, the sultan learned what his pasha had been up to. “Even those who help the sultan gain victory sometimes have his sword unleashed against them.” The sultan once again grew furious and ordered Pasha Mahmud deposed. Unlike Mahmud’s predecessor Judar, Mahmud was to be arrested, humiliated, and executed. Yet again, this is incredibly convenient for the Tarkih al-Sudan author. He gets to claim that the sultan was a righteous fellow totally ignorant of the iniquities wrought by his distant subordinate.

Mahmud managed to escape much of his sentence. He had a special relationship with one of the sultan’s sons, who sent Mahmud a letter via an even faster messenger warning about the sultan’s command. When Mahmud heard what was coming—but before the actual order arrived—he left on a military expedition against a heavily-fortified enemy. He led a small charge against the fort and got himself killed, just as he (supposedly) wanted.

Interestingly, Judar, Mahmud’s predecessor, was still alive and serving in the Saadian occupation. The sultan sent a new commander, who quickly put down the last of the major Songhai resistance. In the peace that followed, the sultan ordered the new commander to share command with Judar. Then the new commander died (poisoned, it was rumored, by Judar) and Judar was back on top, the big winner. Thus the Tarikh al-Sudan author could once again blame any further Saadian excesses on one of the two classic scapegoats: the convenient tyrants Mahmud and Judar. Judar was recalled to Morocco in 1599 and executed in 1606.

At your table, the versions of Mahmud and Judar presented in the Tarikh al-Sudan are fabulously gameable. They are oppressive, cruel villains who keep a secret the PCs can use to topple them, if only the party can learn it: their distant boss would recall them if only he knew what they were up to. Judar and Mahmud are doing their jobs badly. They’re riling people up for no reason, not following orders, and failing to send the full share of the plunder back to the sultan. That’s more than justification for the sultan to send a replacement.

If you apply this template to some planetary governor or hobgoblin warlord who’s already a villain in your ongoing campaign, the PCs might even be in the dark about there being a chain of command above the villain. The villain keeping his oppressed subjects ignorant that even he has a boss both helps him (because no one can get a message to a sultan they don’t know exists) and contributes to his instability (because kings frown on lieutenants who act like they have no king). Or if the PCs know that the villain has a boss, the secret could be that villain is going way outside his appointed powers. Either way, to learn the secret the PCs might get close to someone in the villain’s administration. Or they might intercept the mysterious communications the villain sends off-planet. Or maybe you introduce the idea on accident when the party bumps into a messenger from the sultan.

And of course Judar and Mahmud give us some good villainous activities for the PCs to oppose: making boats out of irreplaceable house parts; betraying the resistance under a flag of truce; arresting scholars and stealing their valuables; and dying in battle to avoid a humiliating execution.

Sing and fight magical folk ballads in 1813 England and Scotland! This free early-access edition has everything you need to play a Ballad Hunters one-shot about the traditional song Barbara Allen.

The game has:

– Investigative adventures centered around the lyrics of traditional British ballads

– Simple, story-driven rules inspired by the GUMSHOE engine

– A historical setting that is grim but hopeful

– Magic where characters make ballad verses come to life

Ballad Hunters is the sequel to Shanty Hunters, winner of a 2022 Ennie Award (Judge’s Choice) and nominee at the Indie Groundbreaker Awards for Most Innovative and Game of the Year.

You can download the free early-access version of the game from DriveThruRPG or Google Drive.

Source: Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John O. Hunwick (1999), especially its translation of the Tarikh al-Sudan (circa 1655)