In 1502, almost a dozen Italian nobles agreed to work together against the ambitions of the Borgia family. This uneasy alliance is a remarkable rogue’s gallery. Some are the worst of the worst: murderers, traitors, and simoniacs. Others are uncompromising politicians, or even decent men spurred to vengeance. It’s the perfect place to draw inspiration for your next villain!

A year before, in May of 1501, Pope Alexander VI (born Rodrigo Borgia) proclaimed his bastard son Cesare Borgia the first-ever Duke of the Romagna. At the time, the Pope wasn’t just the bishop of Rome and the spiritual father of the world’s Catholics. He was also the rightful lord of a stretch of central Italy called the ‘Papal States’. The Romagna was a rural region in the northern part of the Papal States that had been functionally independent for decades, with each small city ruled by its own tyrant, and no one ruling much of the countryside. By declaring Borgia Duke of Romagna, Pope Alexander was giving his son a base of operations from which to further the family’s ambitions of uniting Italy under Borgia rule. Cesare quickly set out to conquer the Romagna and cement his rule over the new duchy.

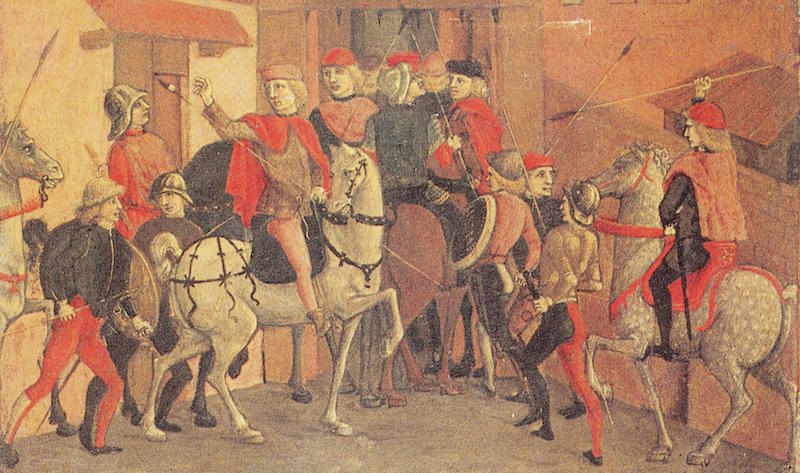

In late 1502, the enemies of Cesare Borgia attended a conclave, intending to unite in the face of their shared enemy. There were a lot of them! The Borgia family’s habits of treachery, impiety, assassination, and naked ambition had made them many enemies. To be clear, it’s not that these traits were unheard of in Renaissance Italy. Far from it! It’s just that the Borgias took them to a whole new level – and were so good at it. The men gathered against Borgia were no saints themselves. Let’s have a look at this rogue’s gallery!

First was Giambattista Orsini. He was a cardinal in the Catholic Church, and the head of the centuries-old Orsini clan. The Orsini were Roman old money. The scorned to the Borgias as upstarts. But Giambattista Orsini had reason to fear the Borgias. He’d watched Alexander VI use the power of the papacy to seize the estates of the Orsini’s old-money peers and rivals. Giambattista had good reason to suspect the Orisni would be next. He called this conclave at his castle in Perugia to unite the region’s squabbling schemers against the Borgias. Despite his cardinal’s robes, Giambattista was notorious hedonist. His dinner parties were almost Roman in their use of wine and orgies. Machiavelli himself would later describe Giambattista as “a man of a thousand tricks.” Between his wealth, his religious authority, and his cunning nature, he was no man to be taken lightly.

Five of the attendees were mercenary commanders currently working for Borgia. Paolo and Giulio Orsini (Machiavelli again: “weak, credulous, and mentally unstable”) obviously had their family loyalties to think about. So too did their friend Vitellozo Vitelli, who was so sick with syphilis he had to be carried in on a stretcher. This was not the first time Vitellozo had betrayed Borgia, though certainly the first time so overtly. In early 1502, Vitellozo took the town of Arezzo, which was under French protection. Borgia didn’t want to anger the king of France, and ordered Vitellozo out. Vitellozo refused. This was all at the urging of his close friends, the Orsini, who were trying to sour relations between Borgia and France.

The last two mercenary commanders were concerned about their lands. Both were minor lords in addition to being mercenaries, and their holdings were along the borders of Borgia’s duchy. They feared that after Borgia finished mopping up in the Romagna, he’d expand his borders by coming after them. Gianpaolo Baglioni was (again quoting Machiavelli) “a man of vicious heart… and great cowardice.” He had “committed incest with his sister and killed his cousins and nephews in order to become ruler of Perugia.”

The other mercenary lord was Liverotto di Fermo. He’d been adopted as an orphan by his uncle, the lord of Fermo, who raised little Liverotto as his own son. Liverotto rewarded him by inviting his uncle, relatives, and friends to a banquet, getting them good and drunk, and murdering them all. Liverotto then killed the last two infants with a claim to being lord of Fermo, and seized the position for himself.

The meeting was the brainchild of Pandolfo Petrucci, the tyrant of Siena. He realized that if Borgia conquered the holdings of Vitellozo and the Orsini, it would open the path for Borgia to attack Siena. The wily old man wanted to keep well ahead of that possibility. Petrucci was ambitious and ruthless. He had married into power, then murdered his father-in-law to consolidate it.

Also present was Ermes Bentivoglio, representing his father, Giovanni Bentivoglio, ruler of Bologna. The Bentivoglios’ interest was simple power politics. Bologna was just north of Borgia’s Romagna duchy, and Borgia had already threatened the city. Giovanni bought him off by handing over a castle along the border. Late in 1501, Pope Alexander VI (Cesare Borgia’s father) had tried to make a grab for Bologna. Bologna was technically part of the papal states, and Pope Alexander tried to summon Giovanni to Rome under accusations of mishandling papal territory. Had Giovanni gone (he didn’t), Alexander would likely have killed him and installed someone more compliant. Furthermore, Giovanni’s son and representative Ermes was married to an Orsini. The Bentivoglios had a deep interest in checking Borgia’s ambitions.

The last attendee of note was a representative of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro. Guidobaldo had a personal reason to want to oppose Borgia. Until recently, Guidobaldo had been duke of Urbino and a Borgia ally. His father had become absurdly wealthy working as a mercenary commander, and spent that money transforming Urbino into one of the cultural capitals of the Italian Renaissance, full of literature and art. Guidobaldo grew up in this beautiful city. As duke, he allied himself with the up-and-coming Borgia family. When Cesare Borgia marched out on one of his campaigns in June, 1502, he asked Guidobaldo for permission to cross Urbinate territory. Guidobaldo agreed. But Borgia betrayed him! He marched into Urbino while Guidobaldo was in the countryside and seized the city. The duke had no choice but to flee. Now the well-cultured but warlike Guidobaldo was out for revenge. He wanted his city back.

While all these men were united in their hatred of Cesare Borgia and Alexander VI, they had nothing else in common. Historically, their families were enemies, fighting over the same land and the same wealth. If the Borgias hadn’t been there, they’d have been at each other’s throats. The whole conspiracy almost fell apart before it began.

But then word reached the plotters that rebels had taken one of Borgia’s fortresses. The castle was being repaired, and the rebels arranged that some long beams be left on the drawbridge. With the bridge weighed down, it couldn’t be raised. When the rebel surprise attack came, the castle was defenseless. Buoyed by this news, the plotters marched on Borgia’s forces.

It didn’t work. Borgia was outnumbered, but he was backed by the wealth of the papacy. He hired more mercenaries and bought off the Orsini family and Vitellozo. The anti-Borgia alliance collapsed. Borgia later pretended to be reconciled with his treacherous commanders. They fell for it, and Borgia had all five strangled. Cardinal Giambattista Orsini died in a papal prison of disease or poison. A conspirator who didn’t attend the conclave, Borgia’s famed military commander Ramiro de Lorqua, was discovered in a public square decapitated, with his head stuck on a lance.

As mentioned at the beginning, this alliance is full of people who would make great villains in almost any campaign. The debauchery and power of Giambattista Orsini, the treachery of Liverotto di Fermo, or the well-placed anger of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro all work at the gaming table without any adaptation.

Separately, you can use the conclave itself as an adventure hook. PCs working for a Borgia-like NPC may be sent to infiltrate the meeting. They might try to replace some of the representatives and spread dissension in the ranks. If the PCs are working for the conspirators, they might intercept messages or rob a mule train carrying pay for Borgia’s mercenaries. One of the folks at the conclave could even send the PCs to find a cunning way to take a castle and convince the conspiracy they must strike while the iron is hot!

(Source: The Artist, the Philosopher, and the Warrior: Da Vinci, Machiavelli, and Borgia and the World They Shaped, by Paul Strathern)