This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

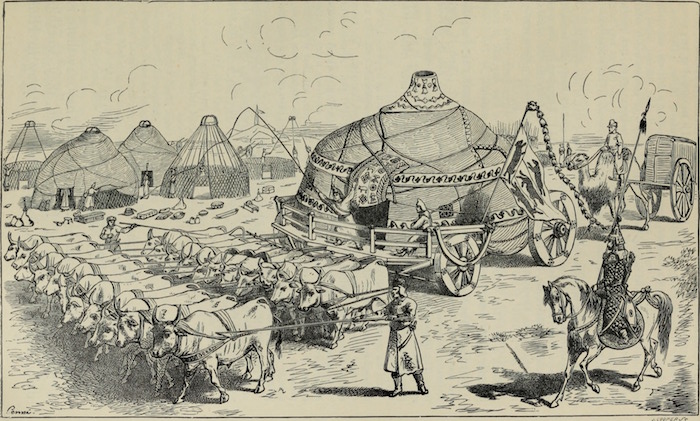

The emperor, Möngke Khan, lived in an orda (tent city) larger and more splendid than any William had seen before. When William appeared before Möngke, the emperor naturally assumed William was there on behalf of all Europeans to surrender to the Mongol Empire. William’s response boiled down to “I’m on a religious mission that’s gotten very out of hand. I promise I’m not here to surrender.” William’s translator was drunk and couldn’t translate much, but Möngke had a translator of his own, a Christian of the Church of the East (discussed last week). No one was quite sure what to do with William. Ultimately, they decided to treat him as a long-term ambassador from a foreign power. They gave his party a small tent and bade them to travel with the orda.

Batu’s orda contained thousands of ambassadors from across the world. Most represented client kings or other vanquished subjects. Some represented states that bordered the Mongol Empire. Their job was to convince Möngke he shouldn’t invade their countries yet. The most colorful envoy was maybe the one sent by the Old Man of the Mountain, the leader of the Isma’ili Assassins. There were also representatives of all the religions found in the Mongol Empire. The incredible diversity of languages and cultures in Möngke’s orda made it probably the best place on earth for cultural exchange – and for the swapping of tall tales.

From Chinese envoys, William heard about a race of furry men just eighteen inches tall. They lived in inaccessible caves. The Chinese lured them out with mead, get them drunk, and then extracted from each three or four drops of blood. This blood they used as a brilliant silk dye. The tiny men were unharmed by the experience, save perhaps for their hangovers. The same envoys assured William that beyond China there was a land were people didn’t age. However old you were when you entered it is how old you’d remain as long as you stayed.

From an unidentified source, William also learned “for a fact” of a land in such-and-such a place where all the animals were tame. The people of that land could gather them up and order them about. But if the animals ever smelled a human from outside that land, they would all become wild at once. So any visitors to this land were locked in a house until their business was concluded, so they didn’t ruin everything.

You may remember from last week that William was not the first Catholic envoy to the Mongol Empire. One of his predecessors, Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, was more credulous than William and breathlessly reported many more wild tales told to him by the other ambassadors. From Giovanni, we learn:

– There exists a land where everyone lives underground because the sun there is too noisy.

– The Gobi Desert is inhabited by mutes with no joints in their legs. If they fall over, they cannot get back up without help.

– In far northern Russia there lives a race of men with small stomachs and tiny mouths. Instead of eating meat, they inhale the steam produced by cooking it. This steam alone sustains them.

– In Circassia and Armenia there lives a race of men with only one arm and one leg apiece. The arm emerges from the middle of their chest. As they cannot walk, they alternate between hopping and doing cartwheels.

– The reason the Mongols never took India is that the Indian king, Prester John, made hollow copper statues, seated them on horseback, filled them with Greek fire, and had men with bellows blow the Greek fire all over the Mongols.

– The people and animals of the Kharan Desert (in southern Pakistan) all look alike. All males – regardless of their species – look like dogs. All females look like human women. The human men of Kharan defeated the Mongol army using ice armor. They bathed their canine bodies in a freezing river and rolled in desert sand. The water froze to the sand in their fur and formed a thick sheet of ice that made them impervious to Mongol arrows. The Mongols are still touchy about the incident and it’s best not to mention it.

While we’re talking about Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, it’s worth mentioning his mission, because it was quite different from that of William of Rubruck. Giovanni carried a letter from the Pope to the Emperor (Möngke’s predecessor Güyük) explaining Christianity and asking Güyük to stop invading people. The letter was serious, but it also served as a cover for Giovanni’s primary mission: to scout out the enemy. There were credible fears another Mongol invasion of Europe was imminent. Indeed, Güyük sent Giovanni home with a letter saying essentially “submit to me or I’m coming for you next.” The Catholic powers saw how swiftly the first Mongol invasion overwhelmed their defenses and sought intelligence on Mongol weaknesses and how best to exploit them. Much of Giovanni’s report on his trip to Mongolia is a detailed description of the equipment, tactics, and organization of the Mongol army.

Giovanni’s recommendations focused on blunting the Mongols’ strengths. The Mongol army could supply itself in the field, unlike Catholic armies which had to buy food as they went, inevitably running out of money after a few weeks and disbanding. So the Catholic powers should pool their wealth into a common war chest to extend the time they can remain in the field. Otherwise the Mongols would just skirmish and harry and wait out their knightly opponents rather than doing battle directly. Similarly, Catholic Europe should agree on a unified chain of command before the Mongols invaded. Otherwise, the Mongols would go after European nations one at a time, winning by division. If Catholic Europe waited until the Mongols arrived to agree who was in charge, it’d be too late. Giovanni also recommended the use of reserves and separate lines that can move independently to defend the hypothetical Catholic army’s rear and flanks, for the Mongols always succeeded in surrounding their enemies.

Giovanni did spot two potential weaknesses in the Mongol army: internal division and hostages. Much of the ‘Mongol’ army was not ethnically Mongol, but belonged to other steppe nations the Mongols had subjugated. Many remained bitter about being conquered. Giovanni felt that if these subject forces could be guaranteed good treatment by a Catholic army, they might turn against their Mongol rulers. The Mongols also had “great love for one another”. If Catholic forces took unhorsed Mongols prisoner rather than executing them on the spot, they might be ransomed back in exchange for “uninterrupted peace or a large sum of money”.

Back to William of Rubruck and his adventures in the court of the Khan. From William’s perspective, the most interesting and troubling of the envoys in Möngke’s orda was an Armenian Orthodox monk named Sergius. He was dark and thin, wore a hairshirt that went down to his knees, and was bound with chains beneath his clothes. Sergius told William that he used to be a hermit near Jerusalem, but that God had told him three times to go to Mongolia and convert Möngke to Christianity. The first two times, Sergius ignored God. The third time, God physically knocked him down, so Sergius packed up his things and left for Mongolia. He’d been working on Möngke by telling the emperor that if he converted, God would ensure he conquered France and the Pope. You might not be shocked to learn that William found this upsetting.

Sergius quarreled with everybody. He denounced the theology of the Church of the East, even though he himself didn’t know his own Orthodox theology: he believed that the Devil made humans out of a slime made from earth taken from the four corners of the world. He started fights with Muslims in the orda, calling them and their prophet “vile dogs”. During Lent, Sergius’ services got so popular that the guards told him the crowd was too big and disrupted life in the orda. Sergius complained about the guards to Möngke Khan and the emperor chewed the monk out for insubordination. Once, Sergius even got thrown out of the orda for a while after he tried to whip somebody.

But the best Sergius story involved a sick priest. This priest, whom William did not name in his report, was the seniormost clergyman of the Church of the East in Möngke’s orda. Sergius assisted William in his ministrations. When it became clear the priest would die, Sergius urged William to leave. If William was present in the tent when the priest passed, he’d be ritually unclean in Mongol eyes and unable to enter Möngke Khan’s presence for a full year. William still hoped he might convert Möngke, so he reluctantly left and the priest died. Sergius then sought William out to tell him that the monk had consulted Mongol shamans to have the priest killed by sorcery, and that Sergius had prayed for this outcome. He claimed the priest opposed their desire to convert Möngke. With the senior priest out of the way, the rest of the Church of the East clergy would be no obstacle and they’d convert the emperor easily to Catholic and/or Armenian Orthodox Christianity. William was horrified, but Möngke had ordered him to live in the same tent as Sergius, so William couldn’t disassociate himself from this weird, murderous sorcerer-monk.

Möngke had a huge orda, but he also had a permanent palace. The Mongol emperors built the city of Karakorum in Mongolia to serve as their capital. Every empire needs a capital, right? The city was reportedly a wonder, built by the finest craftsmen enslaved across Eurasia. But it was also small; Mongolia’s pastoral economy couldn’t support a permanent settlement of any great size. William described Karakorum as being smaller than the village of Saint-Denis outside Paris. Even still it had to be supported by dedicated herds grazed a few days away from the ‘city’.

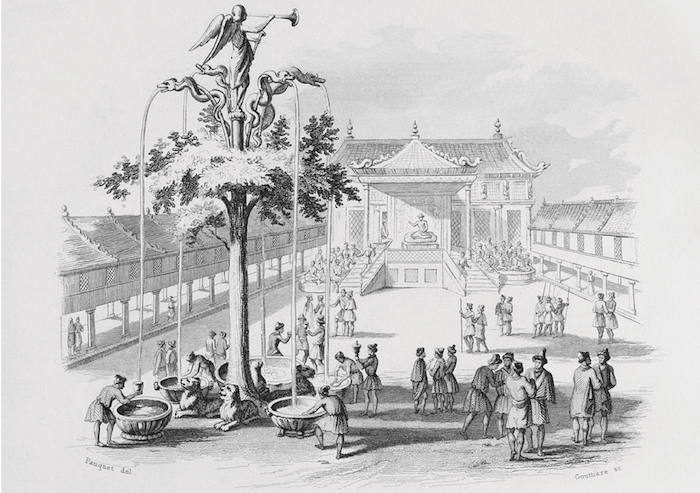

William wrote down an inventory of the contents of Karakorum. There was the palace of the emperor, one church, two mosques, and twelve “pagan temples” (which could be any combination of Buddhist, Taoist, Tengrist, Hindu, or anything else). Warehouses like long barns stored the gathered loot of the empire. There was also a district for Chinese craftsmen, a district for Muslim merchants, palaces for court scribes, open squares for tents to be erected, and even an irrigated garden – a borderline miracle in dry, pastoral Mongolia. The genuine miracle, though, was a clockwork tree made by a Parisian goldsmith enslaved in Belgrade. It dispensed four kinds of alcohol and was topped with an angel that played music.

While William was in Karakorum, there was a rumor that four hundred Isma’ili Assassins from Alamut had infiltrated the court and were preparing to assassinate Möngke. The emperor’s chief magistrate, a man named Bulgai, individually interrogated several foreign envoys to determine if they were secret Assassins. These interrogations especially targeted associates of the Armenian monk Sergius. His troublemaking ways apparently landed him on Bulgai’s list of people to keep an eye on.

The climax of William’s stay at the Mongol court occurred when Möngke declared he would like to see a three-way religious debate between Christians, Muslims, and Buddhists. William didn’t want to participate, since he was afraid it would turn into a debate where the Christians and Muslims argued in favor of monotheism against the ‘pagan’ Buddhists; the friar didn’t want to team up with Muslims for any reason. But Möngke Khan wanted a debate, so William was assigned a good translator and the debate occurred. William was proud of how he did, but the arguments he records just strike me as tiresome.

Finally, William got the best news he could have hoped for. Remember that letter Batu asked him to carry to Möngke? The one that explicitly framed William’s mission as a request for an alliance with Catholic crusaders, instead of as a simple mission of Christian friendship and proselytization? That letter had been lost, and no one could remember what it said. So William was brought back before Möngke to remind everyone why he was at the Mongol court. This time, he framed his task as a goodwill mission, the mission he (incorrectly) thought he was on in the first place. Möngke declared that he had no further need of William and that the friar should go home. William made a last-ditch attempt to convert the emperor, but to no avail. Möngke was unimpressed by the hypocrisy of Christians and would not be swayed. To quote William’s report, “If I’d had the power of working miracles like Moses, he might have humbled himself before God.”

So William returned west. He carried a letter from Möngke Khan to King Louis IX of France warning Louis not to make war on the Mongol Empire. When William arrived in the Middle East, he learned the Seventh Crusade had ended in disaster for King Louis. The king had been defeated, captured, ransomed, and returned to France. William wanted to report to Louis himself, but his clerical duties kept him in Lebanon. Instead, he had to make his report in writing. It’s a fortunate thing, too. If he’d done it face-to-face, less of this information might have survived.

Image credit: Arabsalam. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

At your table, Möngke’s orda is amazing inspiration for an adventure site – especially a political one! You’ve got all these ambassadors in one place. Whatever goal the PCs are working towards in your fictional campaign, if it has an international component, they can probably make some progress on it in a court based on this one. Plus, all the wild stories being told present a great opportunity to float adventure hooks and see what the players bite down on. Not sure whether your players would rather negotiate a succession crisis for Prester John or solve the mystery of who changed the shapes of the creatures of the Kharan Desert? Present both as stories at court and see which your players ask to hear more about.

Plus, there’s loads of adventure hooks baked right into Möngke’s orda. Can the PCs find the secret assassin sent to kill him? What about the gossip who started the false rumor? Can the party convert your fictional emperor to whatever religion they favor? Can they counter (or aid) the weird monk who’s also trying to convert the emperor? Can they rob the warehouses that hold the gathered loot of empire? Might argumentative players enjoy a debate based on Möngke’s religious symposium? And can the party leave the court without the emperor sending a return envoy who might spy on whatever land the PCs are from?

Speaking of spying out the enemy, a note on Giovanni’s mission of secretly scouting out the Mongols. Depending on your group, an adventure based on that goal might or might not be fun. If you’ve got a few of those players who obsess over military history or RPG tactics, tell them what they see at court and ask them for their recommendations. It can be a private puzzle, just for them. They can flip through their splatbooks and Osprey Men-at-Arms books while the rest of the party does other things. If you don’t have such players, resolve such observations and recommendations with a hand-wave. Don’t ask for a roll. It would be dumb if the PCs traveled all this way only to flub the final roll – the one that makes every other roll matter.