The Laurin poem is a Medieval German saga of adventure and conquest. While the story is pretty boilerplate, it has a truly remarkable setting and antagonist: the sylvan realm of gardens, glades, and underground castles ruled by Laurin, the pagan king of dwarves and giants. Let’s ignore the boring stuff and jump straight to the good part!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Laurin’s kingdom was located in the forested mountains of Tyrol, in the Alps. The region today straddles the border between Italy and Austria. The Laurin poem is popular today in South Tyrol, an autonomous Alpine province in northeastern Italy, possibly because Laurin is eventually defeated by the Germanic hero Dietrich von Bern. South Tyrol is predominantly German-speaking, and Dietrich’s victory over the autochthonous (indigenous, literally ‘springing from the ground’) Laurin may be symbolically resonant for the people of South Tyrol.

Laurin’s realm was aesthetically Arcadian: a sylvan idyll of glades and woods and meadows. While his strongholds were underground, the bulk of his kingdom consisted of sun-drenched hillsides and dappled valley floors. Flowers bloomed between the trees. Wild animals played in green meadows. Birds sang in melodic choruses, each contributing to a careful symphony. This was an imagined nature: one not wild, but controlled, intentional, even sculpted. The effect was accentuated by carefully-placed fountains and harps and with art depicting singing birds and prowling leopards.

Laurin’s pride was his beautiful rose garden, tucked away in a hidden valley. The garden was enclosed by a wall pierced by four golden gates. Within the wall, the garden was ringed by a silken thread. Laurin’s punishment to anyone who broke the gates, cut the thread, or harmed one of the lovely roses was to cut off their leftfoot and right hand.

The fortresses of this paradise were hollow hills. Each had a gate with a golden bell or golden horn for visitors to sound and announce their arrival. The interiors of these underground castles were lit with glowing gemstones. Laurin’s own hall was the largest of them all. Here he kept his army of twenty thousand dwarves and five giants. Beneath the hall was a dark dungeon for holding prisoners. And somewhere within was Laurin’s storeroom, where he kept the obligatory wealth beyond imagining.

The inhabitants of the dwarf-and-giant kingdom were pagan, which fit with their sylvan aesthetic and their nature as old creatures, remnants of Germany’s pre-Christian past. The dwarves were explicitly small (not always the case in these sagas), between two and four feet tall. They lived in a society familiar to a Medieval audience, with castellans, knights, foot soldiers, and even a court wizard! The giants lived in the forest, apart from the dwarves. We don’t know exactly how tall they were, but at one point in the poem a giant carries on his shoulder a pole with four knights tied to it. It’s not clear how much interaction the dwarves and the giants had, but they were both loyal to Laurin.

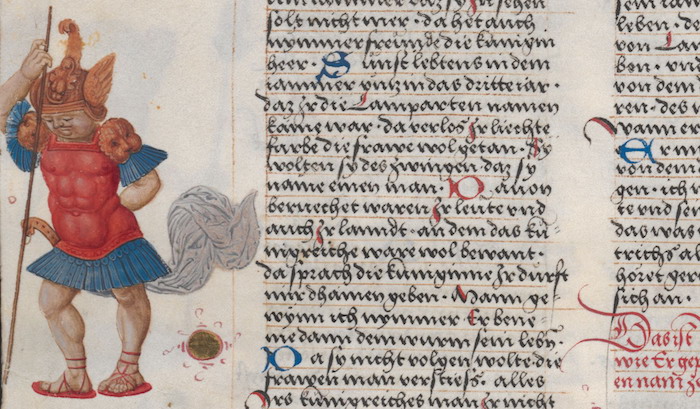

Laurin was himself a dwarf. He was a valiant knight before he was a king, and could cut down a hundred knightly champions in a single battle. He is described as a cross between warrior and hunter. His courser bounded “like a faun”, and he brought two hunting greyhounds with him to war. He wore a belt that granted him the strength of twelve men, unpierceable armor, and a magic crown decorated with birds that really sang. Unsurprisingly for such a man, his first instinct for solving problems was to use violence!

But Laurin was cunning too. When faced with a powerful foe, he preferred guile, trickery, and patience. He turned friends against each other by promising each their heart’s desire. He invited guests into his hall under false pretenses and fed them sleeping potions in place of beer so he could safely imprison them. He was also a sorcerer! He could make himself tall, and carried a cloak of invisibility he used to kidnap the woman he sought to marry. He also sometimes fought while invisible, much to the frustration of his foes.

Laurin’s best trick was for when he had guests he didn’t trust. He had his court wizard cast a spell on the guests so they couldn’t see each other. They weren’t invisible; each was perfectly visible to anyone not ensorcelled. If the guests proved troublesome, the wizard could extend the spell so its subjects couldn’t see anyone, though they could still see the world around them. These precautions made it harder for guests to plot amongst themselves to oppose King Laurin. The spell did not prevent the guests from enjoying King Laurin’s hospitality, so it doesn’t impinge upon his obligations as host.

In a fantasy campaign, a small mountain kingdom modeled on King Laurin’s is a nice change of pace from your standard Tolkeinesque dwarf realm. If your party is traveling there, give them a task that puts them at odds with Laurin: maybe to steal a rose from his hidden garden, spring someone out of his dungeon, or rescue the kidnapped woman he wants to marry. If the PCs know what their objective is, but not how to find it, they might travel to Laurin’s hall to learn more. This gives you an opportunity to have Laurin ensorcel the party until he’s sure what the PCs are up to; it’s a fun obstacle to have to overcome! Meanwhile, Laurin tries to get the individual PCs alone and turn them against each other with promises. If that doesn’t work, he may try to have them imprisoned. If the party gets what they came for, have Laurin and his army pursue them across the Arcadian landscape. The birds and beasts may be his spies, and every verdant hill may conceal a fortress full of soldiers ready to sally forth against the party!

–

Source: Illustrations of Northern Antiquities (1814)