On the coast of Kenya, shrouded in dense bush, the ruins of Ungwana wait for archaeologists. The ruins of nearby Gedi and Kilwa – major trading centers whose coins have been found as far afield as Australia – get most of the attention, while Ungwana decays under vine and root and equatorial rain. Nonetheless, the site has some fabulous features, and it’s perfect for fictionalizing and dropping into a fantasy campaign!

This post is brought to you by beloved PThe Ruins of Ungwanaatreon backer Joel Dalenberg. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Joel, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Image credit: Filip Lachowski. Released under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

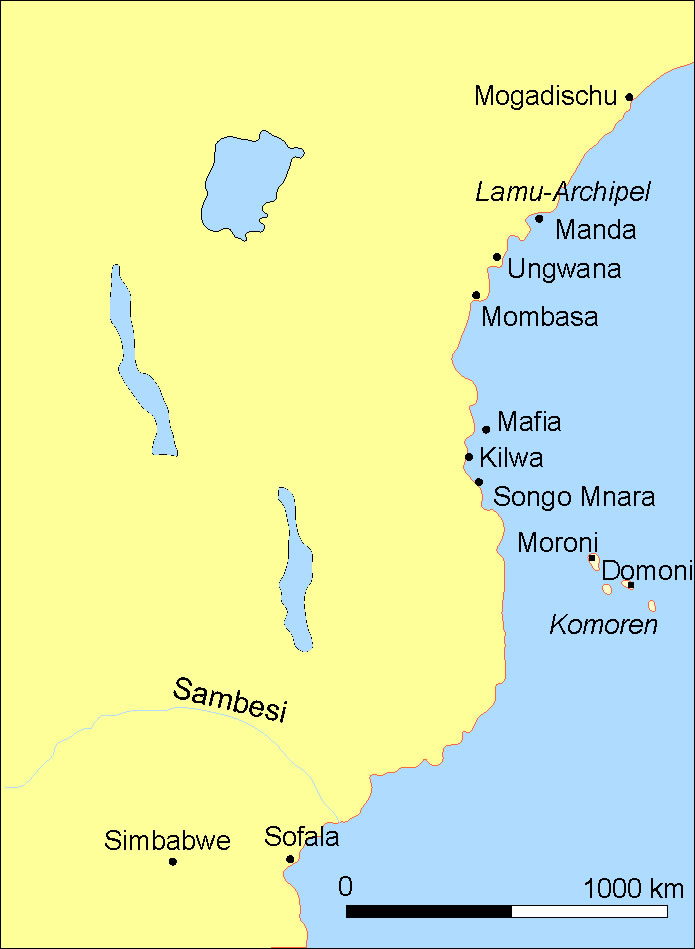

The port town at Ungwana was inhabited from roughly 1200 to 1600 at the mouth of the Tana River. It’s been tentatively identified with Hoja, a port sacked in 1505 by Portuguese naval commander Tristão da Cunha: my namesake’s namesake’s namesake. ‘Ungwana’ is a more recent name. The town was encircled by a stone wall, enclosing an area 300 meters by 600 meters (about 45 acres). A single gate opened directly onto the pebbled beach. The town probably served as an entrepôt, collecting the products of the lower Tana River for transport to other ports accessible by larger, deeper-drafted ships. The primary trade good was probably ivory; no slave pens have been reported at Ungwana.

Though da Cunha destroyed Hoja, the people rebuilt, and the site wasn’t abandoned for another century. Local tradition holds the Ungwanans left under pressure from the Oromo, a separate local ethnic group. In one story, the Oromo demanded the Ungwanans leave and the town quietly and peacefully decamped. In another, the Oromo launched a night attack and massacred the whole population inside the Great Mosque. Since then, the mouth of the Tana River has filled in and shifted west. The ruins are now a quarter-mile from the sea. Roofs collapsed, walls crumbled, and the advancing forest devoured the site. Locals report watching the ruins vanish before their eyes as roots pry apart the stones and rains wash away the mortar.

Who were the Ungwanans? We know many or most were Muslims. They were probably ethnic Swahilis and spoke Swahili or another Bantu language, which they wrote with Arabic script. The elites spoke Arabic and Swahili and may have claimed mythic origins in the Middle East. These are an example of the ‘Arabs’ so often referenced by European explorers of East Africa: not Arab by ethnicity, but by language and religion. Use of the term probably started as a misunderstanding and stuck around because it fit European preconceptions. A literate society that builds large stone towns is surely not African (sarcasm, obviously). Recasting these ‘civilized’ black people as transplants from Arabia made far more sense, especially given that there was probably intermarriage between the elites and seagoing Arab merchants. The term ‘Arab’ stuck around. You still see it pop up without explanation in books talking about medieval and early colonial East Africa.

Image credit: Udimu. Released under a CC BY-SA 2.5 license.

The most impressive structures in Ungwana were two large mosques. They were side by side and shared a wall. These were ‘Friday mosques’ – big enough for the community to gather there for the most important prayer of the week on Fridays at noon. The older of the two mosques probably had ten cupolas and two barrel vaults. The new Friday mosque went up a century after the first. Rectangular cisterns outside the entrances gathered rainwater for pre-prayer ablutions. The remains of three other mosques have been identified in Ungwana. One was decorated much more intricately than the Friday mosques. It’s been tentatively identified as a sort of royal chapel, but that’s just speculation.

The cemetery is full of broken tombs – opened by time, not grave robbers. One tomb, covered in knotwork and weathered decorations, was declared by one researcher “one of the the richest and most elaborate monuments in Kenya”. The earth in the cemetery is littered with potsherds. It was customary to leave bowls of offerings for the dead. But some of the sherds are 20th-century. Who was still coming out here to leave offerings?

A cairn of stones near Ungwana is supposedly the grave of the great Swahili folk hero Fumo Liyongo. He was a king, a warrior, and a poet who purportedly lived somewhere between the 9th and 13th centuries. When his brother falsely imprisoned him to steal his crown, Liyongo escaped and became king – first among equals – of the hunter-gatherers of the plains instead. He wrote self-congratulatory praise-songs, describing himself as “lethal to people; when I take up arms I kill truly; I am terrible in battle when I hear an evil word.” And when he returned to the coast to reclaim his throne, Liyongo carried that inland plains culture with him. He had countless adventures and escapades, all fantastical. In each, he embodied the multicultural crossroads at which the Swahili people stood. Or so the stories say – stories he may have authored!

Image credit: LutzBruno. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 image

Most of the buildings in Ungwana were built from a special kind of stone called ‘coral rag’. It’s a pitted gray limestone that forms under coral reefs. In life, corals are huge communities of little polyps that grow a shared ‘skeleton’. In death, that stony skeleton serves as a base for more corals. Skeleton builds upon skeleton, until the base of the reef is just a solid piece of stone. When seafloor becomes land, the old reef base can be quarried. That means the buildings in Ungwana are made of the coral equivalent of bone. If there is necromancy in your setting, entire buildings in Ungwana could be raised from the dead!

And thematically, that’s what lies at the heart of Ungwana: the tension between life and death. This is a dead town made of dead bone (sort of) that’s being devoured by living forest. If your setting has anything like D&D druids and necromancers, this ruin is the flash point in a conflict between them. It’s a struggle between life and death, with great treants battling animated necromantic houses. If your PCs don’t want to pick a side, who better to mediate than the multicultural culture hero Fumo Liyongo, buried nearby. He’s dead, but if there are necromancers around anyway, that’s not much of an obstacle!

Finally, I’d like to return to those cisterns outside the mosques. They held water for performing wudu, the ablutions Muslims perform before prayer. If your fictional fantasy setting has ritual washing for purification, what happens to that spiritual pollution that gets washed off? Presumably, it remains in the cistern. After four hundred years of accumulating pollution, those cisterns must have a lot of bad magic in there! If water spirits (or similar) were to move into these cisterns, they might be infected by all that badness. They might also have learned from the stones of the building an incomplete (and therefore heretical) version of the religion preached inside. As always, this is why you fictionalize things: the idea of accumulating washed-away badness is nonsensical in Islam, but great for fantasy.

–

Sources:

Ungawa on the Tana by James Kirkman (1966)

More than the stuff of legend, University of Cambridge (2011)

The Epic of Liyongo

Magomero: Portrait of an African Village by Landeg White (1987)

Further excavations were done in the 1990s by George Abungu, who later went on to serve as director of the National Museums of Kenya and Chairman of the International Standing Committee on the Traffic of Illicit Antiquities, but I can’t seem to find his publications. Offhand references in other works provide some clue to the nature of his, and I’ve tried to incorporate what I inferred. I could never get away with this if I were a serious scholar. Lucky for you, I’m just some schmuck with a blog who likes to show his work.