W.J. Livingstone operated a plantation in Malawi in the early 20th century. He was ruthless, capricious, exploitative, and cruel. He worked within the system, leaning on the letter of the law when he could and enforcing the spirit of the law when he couldn’t. His schemes make him a fantastic villain, and he can be easily added to any setting where landlords control large estates!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Magomero, the Livingstone plantation, was located in the Shire Highlands of Malawi. The region was mostly unpopulated following a horrific combination of war, epidemic, and famine in 1862 unintentionally triggered by the bad decisions of W.J. Livingstone’s older relative, the noted British explorer Dr. David Livingstone. When the Livingstone family later (ca. 1890) decided to start a plantation at Magomero, there weren’t many locals left. The upside for the Livingstones was that the local chiefs sold them 169,000 acres of land for really cheap. The downside was that there wasn’t much local labor to farm that land.

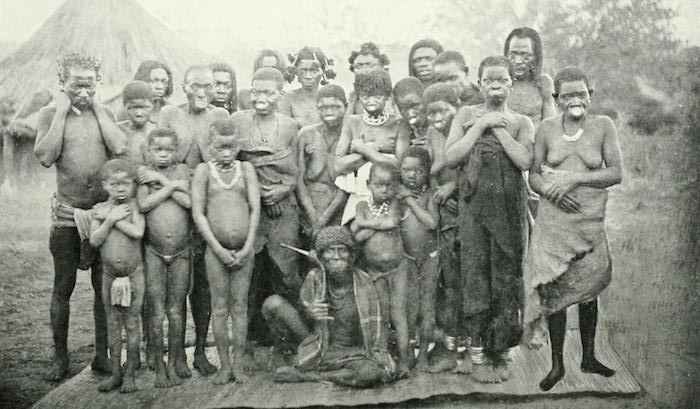

Enter the Lomwe. These were people in neighboring Mozambique dissatisfied with the living conditions and forced labor the Portuguese colonial government made them endure. So starting around 1900, they crossed the border into British-occupied Malawi in search of land. Thousands of Lomwe settled in Magomero. W.J. Livingstone, the plantation owner, allowed them to form villages on his land in exchange for a promise to provide a month of labor on his crops every year. The British saw this as rent, but it was really just corvée labor, a common form of serfdom.

The British colonial government was also trying to find ways to squeeze some money out of the Malawian labor force. Ostensibly, Malawi was a protectorate, not a colony, and was not being run for profit. In practice, the colonial government looked after the interests of the British merchant and planter class. Malawians – who were mostly self-reliant farmers and needed almost nothing from outside the village – had no reason to go work for the English. But without workers, how were the English to make any money? The answer was a hut tax. The colonial government mandated every Malawian family pay a small fee for every hut they owned. Of course, Malawians engaged in a cashless economy and didn’t have actual money with which to pay the fee. So the government ‘permitted’ them to provide a month of labor to a local plantation owner in lieu of paying the tax.

Between the rent and the hut tax, every Lomwe family settled on Magomero owed W.J. Livingstone one male worker to provide two months of corvée labor every year. For the first few years (1903-1905), he didn’t collect. He was still establishing the plantation and didn’t have much work for his laborers to do. But once his cotton fields got going around 1908, his need for labor exploded. The Livingstone family incurred serious debts establishing Magomero, so W.J. Livingstone called upon all his corvée laborers and sent enforcers to rough up anyone who didn’t comply.

The two-month requirement is a bigger imposition than it sounds like. First, the Shire Highlands have a short wet season. The months Livingstone needed his corvée laborers in the cotton fields were the same months those laborers needed to be at home in their own gardens, growing food for their families. Second, some of the Lomwe villages were as far as ten miles away from the cotton fields. Workers had to wake up in the middle of the night, book it to the cotton fields to be present at six A.M. for roll call, work until noon for Livingstone, then book it home and try to squeeze in a little labor beside their wives in the garden. Still, the system – while undeniably exploitative – was manageable. The situation was still better than in Mozambique, and most Lomwe families made it work.

Then cotton yields began to fall. It turned out that cotton was only profitable in the Shire Highlands in its first year. Once the crop began to exhaust the soil, Livingstone couldn’t make it pay. So he had to clear new fields every year, ballooning his need for labor. His debts mounted. He couldn’t afford to buy the farm machinery that might make the crop profitable in the long run. He just leaned harder and harder on his already-overstretched corvée laborers.

By 1910, Livingstone was flagrantly violating the corvée laws. Unmarried women weren’t supposed to do corvée labor, since they didn’t have a spouse to stay at home and grow the food they would actually eat. Livingstone dragged them up to the cotton fields anyway. Soon, many children joined them. And it still wasn’t enough. So Livingstone broke the two-month cap on corvée labor. He ordered his overseers to fudge the books. If your labor didn’t meet their standards, you didn’t get credit for having worked that day. A two-month obligation ballooned into six months. If you failed to show, Livingstone’s enforcers would beat you and burn down your hut. You couldn’t even leave Magomero; you needed paperwork to prove to the government that you’d done your corvée, and Livingstone kept that paperwork close.

The colonial government knew what was going on, but wouldn’t step in. Livingstone was the largest landowner in the Highlands. His debts were huge, but he still had enough money to complicate your career if you crossed him. His name also granted him legitimacy. His older relative, the late Dr. David Livingstone, was a legend in British Africa. No one wanted to up against that name! Finally, and perhaps most relatably, the Magomero estate was conveniently placed. As officials made the rounds of the colony, they overnighted in Livingstone’s guest rooms all the time. There was almost no way around it. If you traveled around Malawi, you would eventually stop at Magomero. And if you had punished Livingstone for his lawbreaking, the stop would surely be awkward. Better just to mind your own business. So, colonial officials’ fear of Livingstone’s wallet, name, and social displeasure kept the Lomwe of Magomero in abject serfdom.

Even fellow plantation owners were shocked by Livingstone’s caprice and casual brutality. He was supposed to pay his corvée workers, but only did so on a whim, and far less than the legal minimum. When touring his estate, he ordered beatings seemingly at random. People learned to hide when they heard his bicycle coming. The British colonial system was undergirded by the fiction that the British were the good guys: that they followed the law and their subjects benefitted from their benevolent rule. This was almost always a self-interested lie, but even fellow colonizers had a hard time maintaining it when Livingstone was around.

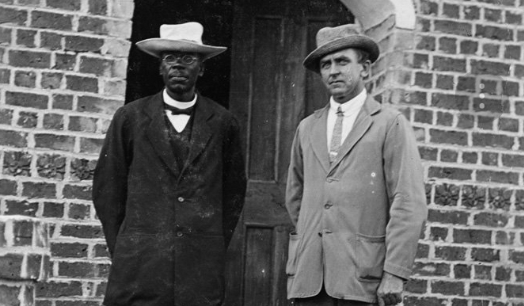

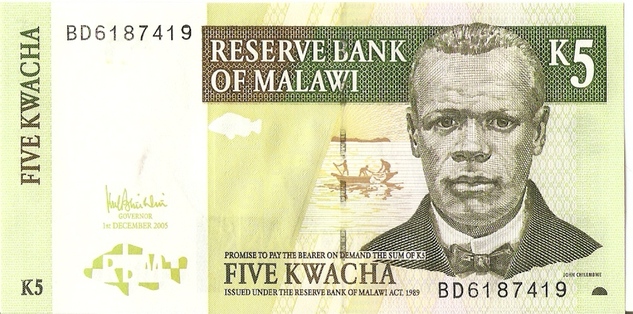

Ultimately, W.J. Livingstone met his match in John Chilembwe, a Malawian preacher. Chilembwe served under a radical Baptist preacher in Malawi who exposed him to the idea of political equality between blacks and whites. Chilembwe then spent two years at a seminary in Virginia from 1897-1899 and was ordained as a Baptist minister, while being exposed to radical American ideas about racial equality.

In 1900, Chilembwe returned to Malawi to preach the gospel to his people and try to lift them up to economic and legal parity with their British colonial rulers. He founded schools and churches, organized a Malawian-run industrial mission, and preached against conscripting Malawians to fight in WWI. At every turn, the authorities tried to stymie him, but had little success. They couldn’t jail him, because he was breaking no laws, and anyway he was popular. His supporters would just bust him out of jail anyway.

After 15 years of preaching, John Chilembwe finally conceded that the British would never permit racial equality. The only solution was to drive them out. He led an uprising in 1915. It didn’t go far. Cells across Malawi were supposed to rise all at once, but most failed to do so. Only the cell Chilembwe led personally accomplished its mission: killing the most hated landlord in Malawi, W.J. Livingstone.

A week later, a British patrol shot John Chilembwe dead.

Image credit: Mo Cuishle. Released under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

At your table, a landlord inspired by W.J. Livingstone would make an amazing villain. This sort of petty tyranny – someone who takes an unjust but manageable system and cranks up the injustice to eleven – is something most of your players should be able to relate to. Even though we’ve (hopefully!) never experienced anything as bad as Magomero, each element of the story is something many players have endured: a boss who expects you to work extra hours without pay, a landlord who doesn’t care what legal protections you have, or a bystander who turns a blind eye because it’s easy. Your players will get this villain, and that extra buy-in should create a better adventure.

In real life, this story ended in violence, but at your table it doesn’t have to! Your players could push through the legal system until they find someone who cares enough to stop your Livingstone-analogue. They could audit his books, get his debtors to collect early, launch an exposé about him in Britain, or dig up blackmail that the colonial government will actually care about. Maybe your PCs have special contacts, skills, or powers, that will help them resolve the situation peacefully! Or, if all else fails, they could go looking for a John Chilembwe analogue and see what they can do to help his uprising succeed.

–

Source: Magomero: Portrait of an African Village by Landeg White (1989)