In the 1580s, a prince of the Songhai Empire in what is today Mali fled into hiding after completing a sensitive mission on behalf of the emperor. He remained undercover for five years, hidden in plain sight, until the coast was clear. Finding the prince without blowing his cover could be a really fun short adventure.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

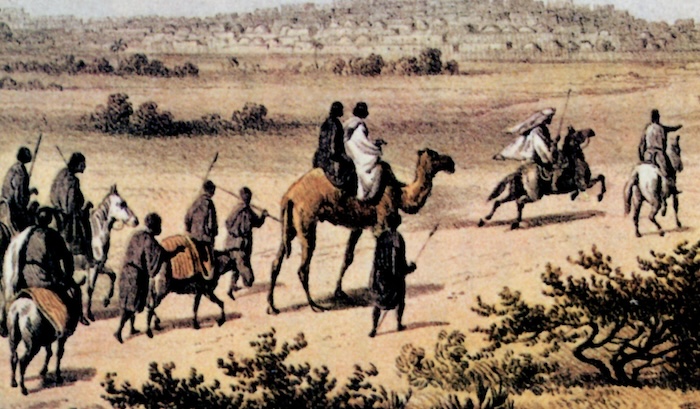

In 1582, a new ruler ascended the throne of the Songhai Empire along the great bend of the Niger River: Askia (emperor) Al-Hajj. The Tarikh al-Sudan (composed circa 1655), one of the better textual sources for the history of the Songhai Empire, has nothing but good things to say about Askia Al-Hajj. He was a nice guy, pious, competent, and able. But soon after ascending the throne, he came down with a disease that kept him from sitting a horse. The text is vague about the condition. Hemorrhoids and sores on his thighs are both consistent with the wording. An Askia had to lead Songhai armies on campaign and fight battles (inevitably on horseback) against rivals and rebels. Askia Al-Hajj simply couldn’t. This weakened his position.

Soon after Askia Al-Hajj ascended the askiate, one of his brothers made a play for the throne. Faran Muhammad Bonkana was the governor of a far western province. When he heard their father was dying, he hurried back to the capital with his army. But his father died while Faran was still in transit and Al-Hajj was already in the capital, able to consolidate power, and became the new Askia. Faran resolved to bring his army to the capital, Gao, and fight his brother. But the route along the Niger River took him past Timbuktu and he stopped to consult with one of the learned jurists (a qadi) there. It seems Faran had a change of heart; he took shelter in the qadi’s home and asked him to write a letter to Askia Al-Hajj to ask permission to remain in Timbuktu and become a scholar. When Faran’s soldiers heard this, they deserted en masse and joined the imperial army. Askia Al-Hajj, being a nice guy, had no objection to Faran’s request. He appointed a new governor, Faran threw himself into his studies, and all was well.

But Faran’s presence in Timbuktu made life hard for the army chiefs in the capital. Their duties required they send frequent messengers to Timbuktu. Every time they did so, gossips would say, “Oh, there goes the messenger of so-and-so to Timbuktu, the town where Faran Muhammad Bonkana lives. If Faran were colluding with the army chiefs to launch another rebellion, this would be the way to do it.” In the American civil service, the goal is to avoid even the appearance of impropriety, and the Songhai army chiefs had a similar desire. As long as Faran was in Timbuktu, it would look like they were plotting rebellion with him. They demanded Askia Al-Hajj do something about the situation.

So Askia Al-Hajj summoned Amar, the son of one of Askia Al-Hajj’s loyal brothers. Amar was thus a member of the royal family. His father would later become Askia. This guy was somebody. Askia Al-Hajj commanded Amar to take a small troupe of cavalry to Timbuktu, arrest Faran, and bring him safely to the capital.

The expedition rode fast and made it to Timbuktu before word reached Faran that he’d been ordered seized. The soldiers found the wall around Faran’s compound was low enough that Amar could see over it while seated on his pony. In the yard was a fine horse, the sort Faran might use to make his escape. Amar took a javelin and hurled it at the animal. The dying horse woke Faran from his mid-afternoon siesta. He realized what must be happening, but without a horse he could neither flee nor fight back. Amar took Faran into custody. Faran would spend the rest of his life in Kanatu, the Songhai political prison.

Amar found little reward for his faithful service. Faran’s sons went into hiding in case Askia Al-Hajj targeted them next. They swore vengeance on their father’s persecutors. Askia Al-Hajj was protected by high walls and an army, but Amar wasn’t. Amar went into hiding for his own protection.

Amar’s hiding place was an organization that is known only from the Tarikh al-Sudan in this particular story. The suma were, it seems, royal attendants whose role was to oversee the ceremonies surrounding the crowning of a new askia and personally serving an as-yet-uncrowned askia until he could ascend the throne. The Tarikh al-Sudan claims the suma wore hooded cloaks that concealed their faces. Amar joined the suma and lived as a servant in the royal palace—his own family’s palace—until the danger was past.

That would take some time. In 1586, Askia Al-Hajj was overthrown by one of his brothers, who was crowned Askia Muhammad Bani. One of the first acts of the new emperor was to order the execution of the imprisoned Faran Muhammad Bonkana. Faran’s sons were still in hiding somewhere in the empire. Their father’s execution presumably gave them more reason to hate Amar. Amar remained among the suma, living as a servant in the palace that now boasted a new master.

Amar was finally able to come out of hiding in 1588, when his own father overthrew Askia Muhammad Bani and became emperor: Askia Ishaq II. With his father on the throne, Amar presumably felt himself suitably protected against whatever Faran’s sons might be scheming. Interestingly, Faran’s sons also came out of hiding at about the same time. They may have figured it was time to call off their five-year-long feud with Amar now that his daddy sat the throne.

At your table, you can have a fictional prince based on Amar living in the palace as a member of a special servant group that wears masks or covers their faces with shawls. The missing prince is just color until the party needs something from him. Maybe their patron has a question about something Amar witnessed on one of his earlier military expeditions. Maybe the PCs have to pass him some important message, or one of his friends is worried about him. Whatever the reason, the PCs have to track down the missing prince. But Faran’s sons are watching them. Can the party find Amar’s hiding place in plain sight without bringing his enemies with them? Heck, if you’re willing to lay the groundwork ahead of time, you might have the party ride with Amar on his expedition to arrest his uncle, thereby embroiling the PCs in the feud with Faran’s sons.

–

Make sure you don’t miss a blog post by subscribing to my no-frills, every-other-week mailing list! I also have a signup that’s only for big product releases!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need! Posts older than a year are behind a very cheap paywall – only $2/month!

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp. On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Blue Sky, I’m @moltensulfur.bsky.social.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on social media, or maybe emailing it to a GM friend of yours. The social media infrastructure that creators relied upon to grow their audiences is collapsing. You sharing my stuff helps me stay relevant and ultimately helps me get paid for my time.

Check out my book Making History: Three One-Session RPGs! It’s three awesome historical one-shots with pregenerated characters and a very simple rules system designed specifically for that story. Norse Ivory is a game about heritage and faith in the Viking Age. A Killing in Cahokia is a murder mystery in the Native American temple-city of Cahokia. And Darken Ship is a horror-adventure starring junior sailors on a U.S. Navy warship who wake up one morning to discover they’re alone on a ship that should carry three thousand.

Source: Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John O. Hunwick (1999), especially its translation of the Tarikh al-Sudan (circa 1655)