In 1531, the askia (emperor) Musa I of the Songhai Empire in what is today northern Mali was overthrown by his brothers. But when they went to place one amongst themselves on the throne, they found one of their cousins beat them to it. This brief power struggle, its actions restricted almost entirely to close family members, is a remarkable story. And if, in your fictional setting, a coup based on these events occurred while your PCs happened to be within the palace, they would be well-placed to reshape the story.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

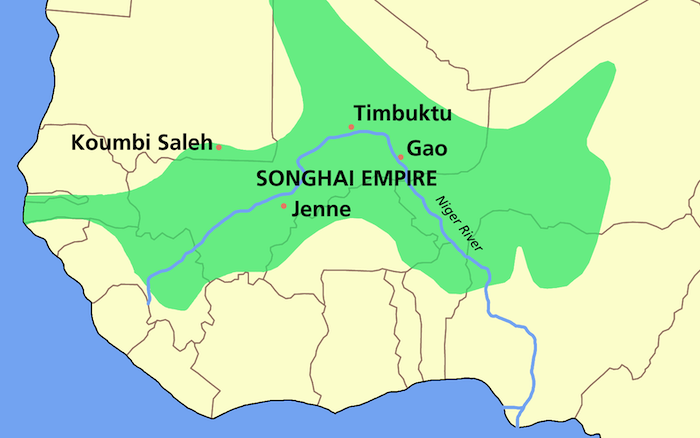

Image credit: Roke. Released under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

The Songhai people historically live in the West African Sahel – the arid scrubland that lies between the Sahara and the green lands to the south. They founded an empire in the 1460s that absorbed much of the old Mali Empire. The Askias (emperors) maintained power through family relationships, charisma, and personal connections among the Songhai cavalry clans. If an Askia’s son or brother was able to supplant the ruler, he often did so. Only a narrow slice of the royal family and Songhai cavalry clan leadership had a say (or perhaps even an interest) in who sat the throne. The other peoples of the empire had their own rulers, and while those rulers had to be approved by the Songhai state, they were largely left to do as they pleased as long as they paid their taxes.

All of which meant that rulership of the Songhai Empire was a family affair. The subordinate populations sometimes rebelled for independence. But since they couldn’t control the Songhai cavalry clans, there was no point in making a claim for the throne. I can only speculate why the clans never made a successful play for the throne in the hundred years before the 1591 Moroccan invasion ended the empire. Maybe the vast number of sons each Askia had made it so every clan always had a relative, favorite, or patsy convenient. Maybe the memory of the dynasty’s founder, the exalted Askia Muhammad, made it unthinkable that anyone but a relative of his would sit the throne. Whatever the reason, whenever one Askia lost power, there was always a scramble to succeed him—but that scramble stayed within the family.

Some quick background on the family situation when Askia Musa was about to meet his downfall in 1531. The empire was founded by a man named Sunni Ali. History has not been kind to him. He had a lot of scholars killed, and the people who write histories tend not to like that sort of thing. His son succeeded him, but was swiftly overthrown by one of his father’s generals, who took power as Askia Muhammad. Askia Muhammad expanded the borders of the empire, established principles of good government, went on pilgrimage to Mecca, and ruled for 35 years. When Askia Muhammad was 70 and blind, his son, Musa, supplanted him. Askia Musa permitted his father to live and even let him stay in the palace. But Askia Musa was paranoid. He executed his brothers left and right. Some of the surviving brothers formed a conspiracy to replace Askia Musa—even as ex-Askia Muhammad was still living in the royal palace.

Image credit: Cheic D. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

So the conspiring brothers made a plan to assassinate Askia Musa. The emperor was traveling with some of his officials and soldiers near his capital at Gao. The brothers, it seems, were part of that column. On the ride, Askia Musa was deep in conversation with the governor of the province of Bara. (In a neat coincidence, the governorship of Bara was denoted by the old Malian imperial title of Mansa, and the most famous of the Mansas of Mali was also named Musa.) No one could get close to the Askia without his permission, but that was no problem. The eldest of the conspiring brothers, Sha-Farma Alu, hurled a javelin at him. He’d made his brothers swear that if he missed, they’d kill him with spears on the spot so no one would think they’d conspired with him. The eldest brother hit—but non-fatally! The brothers had only an instant before the imperial guard would be upon them and, not knowing what to do, all rode away. Askia Musa rode to the royal palace at Gao (where his deposed father still lived) and had the wound cauterized. The next morning, he took his household cavalry and rode out to find Sha-Farma’s cavalry. The two sides met in what our best source, the Tarikh al-Sudan, calls a battle but was probably more of a skirmish. Askia Musa fell. Sha-Farma and his brothers raced to the palace, hoping to claim the office of Askia before anyone else could gather strength.

But at the palace other events were transpiring. A son of the brother of ex-Askia Muhammad—and therefore cousin to both the conspirators and the late Askia Musa—Muhammad Bonkana, viceroy of the western provinces, had sat himself upon the throne. He’d been forced into this rash act by his younger brother, Uthman Tinfaran. Uthman pointed out this might be their lineage’s only chance to take the throne. Otherwise, power would move between the sons of Askia Muhammad and eventually his grandsons and great-grandsons, but never Askia Muhammad’s nephews. Muhammad Bonkana wasn’t thrilled, but Uthman said if Bonkana wouldn’t do it, he would. Since power should normally go to the older brother before the younger brother, Uthman claiming the throne before Muhammad Bonkana would make the latter look weak.

So when the victorious conspirator Sha-Farma Alu entered the palace of the Askia, he didn’t know someone was already sitting on the throne. It seems he didn’t bring troops with him into the throne room; access to the inner courts of the palace was forbidden in most cases, and Sha-Farma had no forewarning of a reason to break the custom. So when he entered the throne room he saw his cousin Muhammad Bonkana seated upon the throne, Uthman beside him. The two claimants exchanged some fiery words (“I do not break down a tree with my head so someone else can eat its fruits”), and Sha-Farma beat the seated Muhammad Bonkana about the head with the shafts of his lances until Bonkana got up (“Ow, stop hitting me!”). Then Uthman hit Sha-Farma with a javelin, and Sha-Farma fled.

Weak, bleeding, Sha-Farma Alu retreated to the river and asked a blacksmith to cauterize his wound. Instead, the blacksmith beheaded Sha-Farma with a sickle and brought his head to the palace. Askia Muhammad Bonkana (for who now would challenge his right to that title?) thanked the blacksmith, then ordered him executed. The Tarikh al-Sudan, doesn’t say why, but it’s easy enough to speculate. The execution sent a message: only royals can kill royals.

Askia Muhammad Bonkana still had one man left to deal with: his blind aged uncle Muhammad, former Askia and founder of the dynasty. Muhammad Bonkana had his uncle removed from the royal palace and placed on an island in the Niger River outside the capital of Gao. This proved to be a mistake. Ex-Askia Muhammad hated living on this island, being croaked at by frogs and eaten alive by mosquitos. Though he was ostensibly powerless, plenty of folks in the empire still owed him favors. He showed his son, Ismail, secret signs he could use to show his debtors that Ismail was acting on behalf of the old man. By calling in these favors, Ismail sowed dissent among the Songhai. Askia Muhammad Bonkana was unpopular among them, for he was forever leading the army on campaigns, but never winning any victories: wearying the cavalry clans without rewarding them with spoils. In 1537, Ismail arranged for the cavalry clans to depose Muhammad Bonkana and appoint Ismail to the position of Askia in his place. Ex-Askia Muhammad was permitted off his island. He died nine months later.

Image credit: David Sessoms from Fribourg, Switzerland. Released under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

At your table, a fictionalized version of this succession crisis is great because of all the moments where a few adventurers in the right place at the right time could have totally changed the story. If the characters happen to be riding in the royal column when the conspirator Sha-Farma Alu throws a javelin at Askia Musa, they might be able to respond quickly enough to jump in front of the javelin or ride down Sha-Farma while he tries to make his escape. If they’re part of the reprisal raid against Sha-Farma where Askia Musa is killed, they might swing the tide of battle a different way—or seek out Sha-Farma the night before and ask what he’ll pay if they betray Askia Musa mid-battle. If the characters enter the palace with Sha-Farma and disregard his insistence that cultural norms be followed, instead accompanying him into the throne room, they might ensure Muhammad Bonkana and Uthman Tinfaran don’t drive off Sha-Farma.

Or, if they’ve not been involved in this mess from the beginning, they might be waiting, unarmed, in a room adjacent to the throne room when Sha-Farma accosts Muhammad Bonkana. If they inject themselves into the squabble, even unarmed they might change the course of events.

This whole succession crisis is that most wonderful of gaming adventure hooks. It’s a messy situation that could go any which way. If your party just happens to be present, they almost can’t help but be sucked in. And once they’re involved, their actions are very likely to have an outsized impact on events. Because the situation is messy, there’s not much for the GM to prep: just the major power-players whose names I bolded above. The historical outcome is a baseline from which the GM can deviate according to how the players impact events. It’s the starting point from which you improvise new outcomes.

–

Make sure you don’t miss a blog post by subscribing to my no-frills, every-other-week mailing list! I also have a signup that’s only for big product releases!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need! Posts older than a year are behind a very cheap paywall – only $2/month!

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp. On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Blue Sky, I’m @moltensulfur.bsky.social.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on social media, or maybe emailing it to a GM friend of yours. The social media infrastructure that creators relied upon to grow their audiences is collapsing. You sharing my stuff helps me stay relevant and ultimately helps me get paid for my time.

Check out Shanty Hunters, my award-winning TTRPG about collecting magical sea shanties in the year 1880, then singing them at the table with your friends. The lyrics of the shanties come to life and cause problems for you and for the crew of the ship you sail aboard. It’s up to you to find clues in the song and put things right!

Source: Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John O. Hunwick (1999), especially its translation of the Tarikh al-Sudan (circa 1655)