This week we’re going to look at a series of bloody, hair-raising adventures from the autobiography of a 17th-century nun, conquistador, murderer, and transman. Lieutenant Erauso was a celebrity in his own day, and his tales of mischief and mayhem across South America make terrific templates for RPG adventures!

I’ll talk more about identifying Erauso as trans at the end of this post. For now, I’ll note that I use male grammatical forms in this piece because Erauso himself did so in his Spanish-language autobiography. For now, on with the blood!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Joel Dalenberg. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Joel, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Lieutenant Erauso was born Catalina de Erauso (assigned female) in 1585 to an aristocratic family in Spanish Basque country. Erauso’s three older brothers were conquistadors, expanding the borders of the Spanish Empire through blood and oppression almost a century after Pizarro’s conquest of the Incan Empire. Erauso was shipped off to a convent around puberty to receive an education until a suitable husband could be found or – failing that – to remain there as a nun. Erauso had no interest in marriage, being a nun, or being a woman. At age 15, he snuck out of the monastery, cut and stitched his nun’s habit into a suit of mens’ clothes, and hit the road under the name ‘Francisco Loyola’.

Erauso found work as an assistant or page for a series of progressively higher-ranked men. Each time, he traded on his good education and quick wit to get the job and used the job to obtain a finer suit of clothes. In this era, the clothes truly made the man, and a set of upper-class clothes were often the only introduction you needed. At his high point, Erauso served as page to the king’s secretary, Don Juan de Idiáquez. But after seven months with Don Juan, who should call on the secretary but Erauso’s own father. Erauso and his father stood in the same room, but his father didn’t recognize him. As I’ve mentioned in a previous post about female soldiers in disguise, people usually see what they expect to see: in this case, only a young page boy.

Erauso’s father was calling upon Don Juan to report that Erauso had disappeared from the convent. Don Juan’s ancestors founded the convent, and the secretary was its current patron. What happened there was his business. Furthermore, Don Juan and Erauso’s father were friends. Don Juan expressed grief and shock that so terrible a thing could have happened and promised to keep an eye out for young Erauso. Erauso, meanwhile, hearing the anguish in his father’s voice, stole away from Don Juan’s house and never returned.

Right from the get-go, we have an adventure suitable for the table: the king’s secretary (or someone else important) comes to the PCs and asks them to search for a disappeared youth. Said youth is currently serving as the secretary’s own assistant. But the secretary is none the wiser, for the assistant is the opposite gender from the searched-for youth, either as a matter of self-expression (as with Erauso) or as a way to hide (as in Shakespeare). Once the PCs find the youth, can the secretary be trusted with the facts they’ve uncovered? If the youth has run away for a good reason, might it be better for the party to claim they failed in their search?

After several more years bouncing around Spain under various names, an eighteen-year-old Erauso set sail for the New World in 1603 as a ship’s boy on a galleon. In Panama, he jumped ship and continued his trend of working as an assistant, then moving on to another employer when the mood suited him. More and more often, Erauso’s departures were precipitated by violence. He’d get in a knife fight over a card game or a sword duel over someone blocking his view in the theater. Other folks would get involved, someone would wind up dead (often murdered by Erauso himself), and he’d have to skip town before the law or the dead man’s friends caught up with him. In this way, Erauso worked and murdered his way through New Spain to Peru. There, he seduced his employer’s wife’s sister. His employer fired him. Erauso soon ran out of money.

But there was one option always available in Peru to a young Spaniard with a taste for blood: to sign on as a soldier. Spain was always trying to conquer one Indian nation or another, and the Indians by now were pretty good at making Spain bleed for the ground it gained. The colonial army was forever hemorrhaging soldiers. Anyone willing to murder Indians by the cartload and probably get killed in the process was welcome. Erauso got his first year’s salary up front as an incentive and was dispatched to Concepción in Chile.

There he had a stroke of luck. The governor came down to inspect the new troops. So did the governor’s secretary, who was none other than Captain Miguel de Erauso, Erauso’s older brother! They’d never set eyes on one another, but Erauso knew him from letters. Captain Miguel asked Erauso what town he was from, and Erauso answered honestly – not that he could have disguised his accent anyway. Captain Miguel embraced Erauso as a brother (not knowing that was literally their relationship) and asked if this new arrival had news from their hometown, especially about his family, including his sister Catalina, the nun. Captain Miguel used his sway with the governor to have Erauso kept from the front and they lived happily for three years as best friends in Concepción. They often visited Captain Miguel’s mistress together. One time, Captain Miguel caught Erauso visiting said mistress without him (if you catch my drift), and they brawled in the street. They soon made up, but Erauso had branded himself a troublemaker and the governor dispatched him to the front. We’ll skip over the eight years Erauso spent at war except to note that he killed an astonishing number of Indians and was promoted to lieutenant.

After almost a decade of continual warfare, Erauso was ordered to return to Concepción. He fell back into his old habits. He was playing a card game with another lieutenant and the man yelled at Erauso that he “lied like a cuckold”. So Erauso drew his dagger and killed the man. Other people came running, there was a brawl, and Erauso killed another man – this one a judge. Erauso fled to a nearby Franciscan church and claimed sanctuary. Legally, as long as he stayed in that church, he couldn’t be arrested. The governor was livid. He surrounded the church with soldiers. Erauso lived in an effective state of siege for six months inside that church before the governor decided this wasn’t a great use of his troops and lightened the watch.

During the siege, friends came to visit Erauso. One asked him to be his second in a duel. Erauso thought the watch on the church was light enough that he could sneak through, so he agreed. On a terribly dark night, Erauso slipped out and joined his friend. They met the opposing party, and the two duelists began to fence. Erauso’s friend was stabbed, and Erauso leapt in to defend him. (I’m not sure if this was a peculiar feature of Spanish dueling or if this was just Erauso defaulting to violence.) The opposing second leapt in as well, and as the two primary duelists lay bleeding out in near-total darkness, Erauso stabbed the other second in the chest. “Traitor, you have killed me,” cried the opposing second – but Erauso recognized the man’s voice. It was his brother, Captain Miguel!

Erauso ran to a nearby Franciscan monastery to find a priest to hear the confessions of the three dying men. The governor placed the monastery under siege just as he’d done with the church. This enforced solitude gave Erauso a chance to grapple with the fact that he’d accidentally killed his own brother. After eight months, Erauso slipped through the siege. He crossed the altiplano to Bolivia with barely any water or food, almost starving in the process. He had many further misadventures in Bolivia, most of which we’ll skip over.

Two details from this business jump out as being gameable. First is a midnight duel where someone the PCs kill turns out to be a relative. It might require some setup to make the twist feel believable, but if you can pull it off, it’d be one heck of a shocker. It’s worth mentioning, though, that you need to be careful about killing off PC relatives. If you tell the player, “Hey, you have a brother and his name is Miguel,” that player is probably not going to care about Miguel. If you ask your player if her PC has a sibling and she says, “Sure, my brother Miguel is a captain in the army,” then she has a decent chance of caring if Miguel lives or dies. But if you make a habit of killing off PC relatives for drama, your players will probably stop inventing relatives for you to kill.

The other detail is that of legal sanctuary. Why did it never occur to me what an amazing plot device sanctuary is? Why have I not filled every church in my campaigns with ne’er-do-wells dripping with adventure hooks (maps to lost treasure, dying parents they need to visit, dead lovers they need to avenge), all desperate for the PCs to help them sneak past the soldiers besieging the church? Why have I not started any campaigns with “You’re all on the run from the law, and you’ve all fled to the same church. What crime did you commit and how long have you been here?”

In Sucre, Bolivia, Erauso befriended the servant of one Doña Catalina de Chaves, the highest-born lady in the area. Doña Catalina generously let Erauso stay in her house. On Holy Thursday, while Doña Catalina was going through the stations of the cross, she had an argument with one Doña Francisca Marmolejo about which of them should have the honor of the first pew in the church. The argument grew heated, and Doña Francisca struck Doña Catalina (Erauso’s patron) with her clog. Doña Catalina stormed back home with her friends, relatives, and backers. Doña Francisca stayed in the church with her party to guard the pew. Everyone feared there would be blood.

Doña Francisca returned home that night under escort by constables, knights, and government ministers. Suddenly, there came the sound of swords on swords. Many of Doña Francisca’s protectors sped off to address the situation. As they did so, an enslaved Indian ran past Doña Francisca and cut her face with a razor. He was gone before anyone realized what had happened. The Indian ran to the home of Doña Catalina, where Erauso was staying, and reported, “The deed is done.” Government officials questioned everyone in Doña Catalina’s home. In one of the interviews, someone accused Erauso of having attacked Doña Francisca in Indian garb and a wig. A judge tortured Erauso, even though as a Basque aristocrat, he was legally protected. In the end, the government acquitted Erauso and released him.

Two proud doñas squabbling over a pew sounds like a great situation to thrust your PCs into, especially if they (like Erauso) owe a favor to one of the doñas. Put the PCs in the church as things are heating up towards a possible clog-bonking and see how they react. Whichever doña storms off may ask the party to avenge her wounded honor and get that pew back. Maybe there’s a violent act of retribution and the PCs have to get to the bottom of it. And maybe after all is done, you can announce that a traveling preacher will soon come to town and the PCs have a need to either impress or kill him. Either way, they now need to get the front pew for themselves (so the preacher thinks they’re the senior group in town or so they have a clear shot), and will have to do social battle with those two doñas over the pew – but with the consequences of their actions in the previous pew-fight impacting the situation.

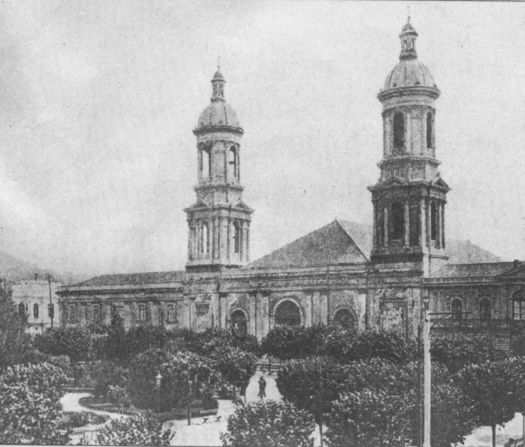

Credit: Wellcome Library no. 282i. Released under a CC BY 2.0 license.

From Sucre, Erauso traveled to Cochabamba on behalf of his latest employer. He had business with a Navarrese aristocrat there, one Pedro de Chavarría. One time that Erauso came to call, there was a crowd of people outside. From the window, Chavarría’s wife – Doña María Dávalos – called out to Erauso, “Take me with you! My husband is trying to kill me!” Then she leapt from the window. The crowd informed Erauso that Chavarría had found Doña María in bed with another man (the bishop’s nephew), had killed the man, locked up Doña María, and was probably going to kill her too. Two friars lifted Doña María onto Erauso’s mule, and off he rode back towards Sucre.

Erauso and Doña María rode all through the night, but in the first light of dawn they saw someone chasing them: Chavarría, Doña María’s husband, his horse half-dead from exhaustion. Erauso and Doña María had a good head start on him, but he must have known a shortcut. Thirty yards out, Chavarría leveled a rifle and fired. The shot missed, but it was a near thing. Erauso spurred his mule down a brambly hill to break Chavarría’s line of sight. The man’s horse gave out, and Erauso and Doña María made it to Sucre, where an Augustinian convent gave Doña María shelter. Then who should appear again but Chavarría, sword in hand! He and Erauso fought all the way into the church, where Erauso drove his opponent against the altar and stabbed him between the ribs. Chavarría lived, Erauso’s employer defused the situation, and no one was sentenced for any crimes.

Rescuing the fair maiden on your dashing steed is a sexist cliché, but Erauso shows us a variant that’s a lot more interesting. Send the PCs to a town to meet a particular NPC, but it turns out the NPC is a murderer and a spousal abuser, and the PCs have to get the (cheating) spouse out of that situation pronto. Then you have a chase scene, opportunities for roleplay with the spouse, and a climactic fight at the end. As far as adventure templates go, this one is both straightforward and interesting.

Eventually, Erauso’s violent tendencies caught up with him. He killed a man over a card game (again) and skipped town to escape the man’s friends. The friends pursued, and Erauso killed several while bouncing from place to place. This spree of violence attracted the attentions of sheriffs and constables across Peru. Several tried to arrest him, and most died at Erauso’s hand. The law eventually cornered him in Ayacucho, where there was nearly a pitched battle in front of the cathedral: government troops vs. Erauso and some Basque friends. To prevent further bloodshed, the Bishop of Ayacucho sheltered Erauso in the cathedral. Erauso had reached the end of his rope. Driven perhaps by religious guilt or perhaps by the hope that doing so might forestall a death sentence, Erauso admitted to the bishop that he’d been born Catalina de Erauso, had once been a novice in a convent, and had fled before taking final vows.

This shocking revelation immediately halted attempts to arrest Erauso. The bishop transferred him to a nunnery, where he was made to live as a nun in nun’s clothes for over two years until confirmation came from Spain that Erauso had never actually taken holy orders. He was free to leave the convent. Erauso returned to Spain, where he was a celebrity. The pope gave him dispensation to continue wearing men’s clothes, and if anyone tried to stop him, Erauso’s memoirs don’t mention it. The king granted Erauso a pension, his surviving brothers got promotions, and he returned triumphantly to New Spain. He lived the rest of his life in Mexico as a slave-owner and minor merchant going by the name of Antonio de Erauso.

It is dangerous to interpret gender and sexuality in the past using modern standards. Both are influenced by their contemporaneous cultural context. It is always tempting to look at people in the past and say that, were they alive in 21st century America, they’d identify as trans or gay or bi or ace or just generically “queer”. That desire is justifiable, but we have to be careful. That same person might express who they are differently in a different cultural context. Still, there’s a credible argument to be made that Erauso was trans. Spanish is a gendered language, and he used mostly male grammatical forms to refer to himself in his memoirs. Even after his secret was out, he continued living as a man and using a man’s name. Writer Pedro del Valle said Erauso told him he used a painful poultice to shrink his breasts. Even given the dangers inherent in identifying a past person as trans, I don’t think it’s much of a stretch for Erauso.

–

Source: Lieutenant Nun: Memoir of a Basque Transvestite in the New World, translated by Michele Stepto and Gabriel Stepto (1996).

Obviously, you have to take the details and particularly wild claims in Erauso’s autobiography with a grain of salt. But he was a celebrity in his own day; if he claimed to have done something totally out of line with the facts, he probably would have been called out on it in the past 400 years.