Last week, we dug into the West African griot-song The Epic of Sundiata, about the eponymous founder of the Mali Empire who lived circa 1217-1255. Sundiata’s mother dominates the first half of the epic, and she makes a fabulous NPC! This week we’re going to look at the second half of the epic through a different lens: Sundiata’s nemesis, the evil sorcerer-king Soumaoro Kanté! He’s a great villain in the epic, and if you file the serial numbers off of him, he can make a fabulous villain in your RPG campaign too!

I’m running a Kickstarter campaign right now for an early-access zine edition of Ballad Hunters, my RPG about magical folk ballads in 1813 England and Scotland. You should check it out!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

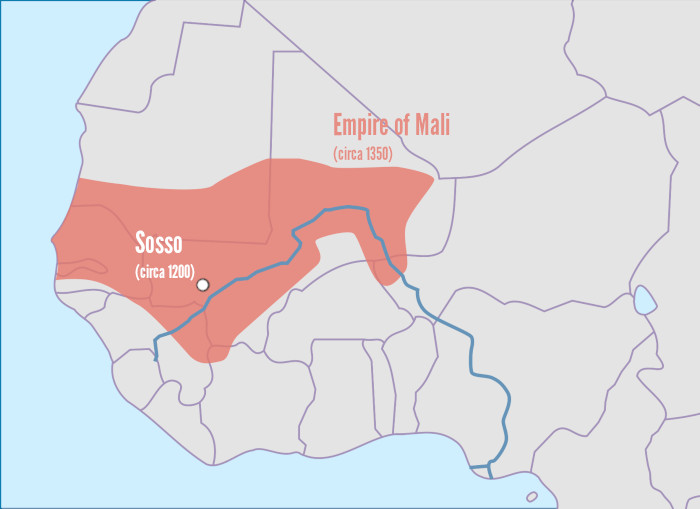

Soumaoro Kanté rose to prominence in a power vacuum following the decline of the old Ghana Empire (no relation to the modern nation of Ghana). The West African Sahel – the arid scrubland that lies between the Sahara and the green lands to the south – was without an overlord. Soumaoro thought he could fill that void.

In The Epic of Sundiata, Soumaoro was a tall man with a helmet bristling with horns. He was descended from the first line of smiths to make fire and forge iron. All smiths have some magic, but this lineage was particularly potent. Soumaoro had a whole army of smiths – fearsome not just for their minor sorceries, but also because they could make for themselves the best weapons. Soumaoro built a triple wall around his home town of Sosso to make it impregnable. In the center of the town he built a seven-story tower in which to work his evil.

In the epic, Soumaoro’s reign produced nothing but bloodshed and grief. His greatest joy was to have old men publicly flogged. He violated ancient taboos. His capital was a fortress against the word of God. He abducted so many young women without marrying them that there were whole towns populated only by these captives. Those whom he did marry were of noble birth. These he kept in the palace compound over which loomed his tower. The most prominent of his imprisoned wives was Kelaya, whom Soumaoro had stolen from her former husband, the sorcerer’s own nephew. This was considered incest, but Soumaoro was so far gone he didn’t even care about that. Every cultural norm his people had, he violated.

Soumaoro’s magic was great. He could shapeshift into sixty-nine different forms. Some, like the fly, let him escape danger or torment his victims. Other shapes, like the wind, were more abstract. Soumaoro could deal death at a distance. He could teleport. He could send owls to speak his messages. Even the mighty jinn had revealed themselves to him. He was invulnerable. Spears bounced off his body. He could even catch arrows mid-flight.

Soumaoro worked his most potent sorceries on the seventh story of his tower. In a chamber decorated with tapestries of human skin, he kept his artifacts and totems. One was an earthenware jar full of water in which lived a giant snake. Around the jar’s base were the nine skulls of the nine kings Soumaoro had killed. Another artifact was the perch for Soumaoro’s owls, who sat at the head of his bed. His throne was decorated with the flesh of his enemies. Weird weapons and cutting implements hung on the walls.

But the most remarkable item was a magic balafon: a xylophone that uses gourds as resonators. This balafon produced music more beautiful than any other. Soumaoro played it while he sang praise-songs to himself – another perversion, since that task should have been done by griots (bards). The instrument was tuned to Soumaoro’s soul. Other people could play it, but Soumaoro would know the instant it happened. Music from the sorcerer’s balafon made things right. It subdued evil and restored partial life to the unjustly slain, including the nine skulls of the nine dead kings. Of course an evil sorcerer would keep this wonderful instrument locked away where it couldn’t help anyone. Of course he’d pervert its purpose by using it to accompany praise-songs to his villainy.

A total aside: today, in the village of Nyagassola in northern Guinea, an ancient griot lineage maintains a balafon that they say is Soumaoro’s. They intimate his was the very first balafon, given to him by a jinn. The balafon tradition is alive and well today – just with a little less ‘skins of your enemies’ vibe.

Image credit: Yedidiamaureen. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

When Sundiata, the prophesied last conquerer of the world, marched against Soumaoro, the magician was arrogant. He knew the prophecies but paid them no mind. He didn’t even bother to stop subduing a rebellion led by the nephew whose wife he’d stolen. He just sent a detachment led by his son to face Sundiata. It took Sundiata spanking the sorcerer’s detachment and sending its terrified commander back to Sosso for Soumaoro to take his army of smiths against Sundiata.

By then, one of Soumaoro’s wives snuck word of the sorcerer’s secret weakness to Sundiata. All men have a tana, a hereditary taboo. Soumaoro’s was the spur of the rooster. Even this violator of all taboos couldn’t touch his tana. If he did, his ancestors would withdraw their support and he’d lose his magic.

So Sundiata made an arrow tipped not in iron but with the spur of a white rooster. When they met on the battlefield, Sundiata’s shot just grazed Soumaoro on the shoulder – but it was enough. The sorcerer’s powers deserted him. He fled into a cave. Sundiata pursued. Soumaoro’s jinn allies took pity on their former master. They performed one last act of service for him: they transformed him into a stone, so Sundiata could not capture him.

When the allied armies led by Sundiata took the triple-walled town of Sosso, they found the animals in Soumaoro’s tower were dying. It seemed it was he who sustained their magic, not the other way around. Sundiata had all the residents massacred and the town burned to the ground.

Image credit: Syrio. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

At your table, the sorcerer Soumaoro is a fabulous villain for a fantasy adventure. I really like how his villainy is culturally-specific. We know he’s bad because he violates specific norms about how to treat the elderly, when to follow taboos, how to respect Islam, and what kinds of relationships count as incest. That’s great inspiration for your fictional fantasy villain. Using your own reasons for why your dude is bad really lets you show off what’s special in your fictional setting. It also makes the details of the setting matter. There’s little I hate more in a fantasy RPG than a bunch of setting details that will literally never impact the decisions the players are faced with. It’s just more pointless detail the GM expects me to remember. But if you tie the unique details of your setting into what exactly makes the villain villainous, it makes those details relevant. They become arguments the characters can use when amassing allies and sore spots you can poke at with the bad guy’s minions.

In an adventure based on Soumaoro’s story, the party hears about this dude and (hopefully) decides to do something about him. You don’t have to do a big battle sequence if you don’t want to (though I do have a whole bunch of advice posts about it). Instead, you can center the adventure around finding the villain’s weakness. In this story, it’s the spur of a rooster. At your table, make sure the weakness shows off something cool about your setting. The PCs might infiltrate the villain’s palace to speak to his wives. They might seek out a distant oracle. They might contact the jinn. During this phase, Soumaoro is probably too arrogant to send serious firepower after the PCs, so everything can stay nice and level-appropriate. Once the PCs have the villain’s secret weakness in hand, they have to apply it to him, and then wham, bam, on to the next adventure!

Finally, I love the list of magic powers The Epic of Sundiata provides for Soumaoro. I’m a real sucker for culture-specific spell lists. They show off what a society thinks is cool, dangerous, and magical.

To restate from last week a few details about the epic, there are many versions, presumably composed at different times – though the events the epic recounts occurred in the 1200s. Some details in the epic are confirmed by outside sources from within a hundred years. Others are unconfirmed. It’s also a great work of literature and a device griots (West African bards) use to reinforce cultural beliefs and norms. You can’t treat the text uncritically as a historical source – but you shouldn’t treat any historical document uncritically, so what else is new? This post is really just skimming the surface of one detail of this delightfully multilayered work.

I’m running a Kickstarter campaign right now for an early-access zine edition of Ballad Hunters. It’s a tabletop RPG where amateur folklorists fight magical folk ballads as agents of the Crown in 1813 England and Scotland.

The folk ballads of the common people are coming to life. Where ballads are sung, sometimes the lyrics take hold of people, forcing them to act out the events of the song. Enchanted victims take on the roles of characters in the ballads. Imagery and danger from the songs manifest supernaturally. Sing old folk songs at the table, anticipate these strange events, mitigate the damage they cause, and help people where you can.

Ballad Hunters is a sequel to the award-winning TTRPG Shanty Hunters and is powered by the GUMSHOE engine. The zine I’m crowdfunding is a small, early-access version of Ballad Hunters.

–

Source: Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali, recited by the griot Mamadou Kouyaté, translated into prose French by D.T. Niane and published in 1960, then translated to English by G.D. Pickett and published in 1965.