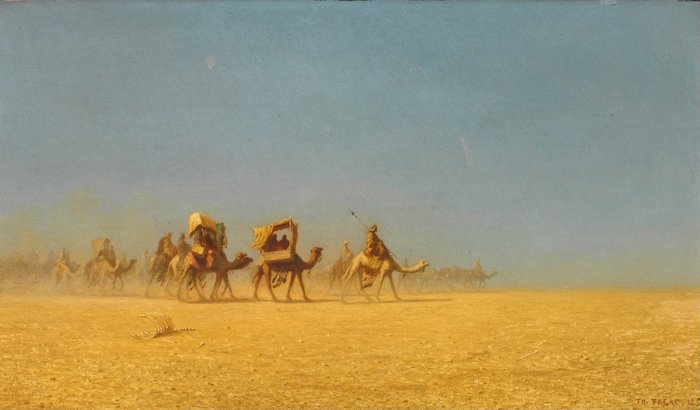

Caravans are the ships of the desert, and they can wreck just as surely as an ocean liner. Not every camel train that went into the Sahara came back out. The discovery of a caravan wreck is a great jumping-off point for an adventure! Let’s piece together some cool bits of history to flesh out this hook!

In 1964, a four-man expedition set out in search of a wreck in Mauritania. The explorers were an antelope hunter named Salek ould Guejmoul (who knew roughly where the wreck was), a French scholar named Théodore Monod (who wanted to see it), and two Mauritanian soldiers (for protection from bandits). They had six camels: one for each rider, one to carry the water, and one to bring back any artifacts. It was ten days out and ten days back across the featureless dunes, with only enough water to spend a few hours at the site.

The wreck, the Ma’adin Ijafen, was a little hillock less than a meter tall. A few brass ingots protruded from the top, as if marking the location. A spread of cowrie shells lay atop the surrounding sand. Monod’s hasty excavation of the site uncovered six bundles of brass ingots, totaling about a ton of metal, buried beneath several sacks of cowries. This was enough cargo for five or six camels. The brass was almost certainly intended for making into jewelry, weapons, and copperware. The cowries were money; the shell of the sea snail Monetaria moneta was used as currency across much of medieval Africa and the Indian Ocean. It’s possible there may have been more treasures buried at the Ma’adin Ijafen. The site was soon swallowed by the sands and lost.

The only thing we know for certain about the origin of the Ma’adin Ijafen is that it dates to between the 11th and 13th centuries, judging by the cloth the ingots were wrapped in. Beyond that, all is speculation. It could certainly have been an ordinary wreck, the result of accident or disaster. But the cargo seems to have been deliberately buried. The protruding ingots suggest a landmark, to help someone find the spot again. Perhaps the Ma’adin Ijafen was the plundered booty of desert bandits who left the plunder to go fetch enough camels to bring it to town and sell. Monod himself favored a scenario where five or six unloaded merchant caravan camels broke loose at night and fled, and their cargo had to be left behind. We really have no way to know.

So now we have the the premise of an adventure: rumors of a caravan wreck of brass and cowries, lost somewhere in the desert, waiting to be discovered and plundered. But we need a little more to make this a fun session. For that, we turn to the memoirs of the 14th-century Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta!

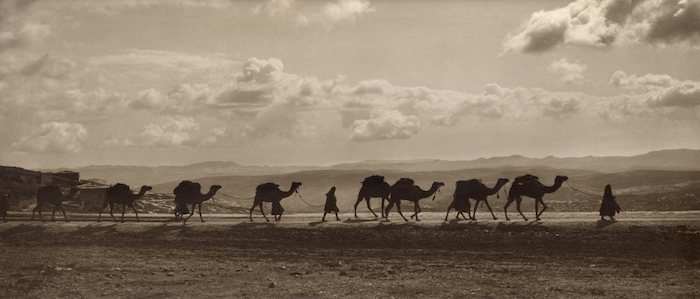

In 1352, Ibn Battuta traveled with a caravan across the Sahara. The column departed Sijilmasa in Morocco with a load of luxury goods. They were bound southwards through mostly rocky desert. They traveled around dawn and dusk, pitching their tents in the hottest part of the day. For the last stretch, it was so hot the caravan could only travel at night. After two months, the caravan arrived in Oualata, which is in modern-day Mauritania, but was at the time a frontier outpost of the kingdom of Ghana. There, the merchants exchanged their cargo for gold and slaves and returned north.

Ibn Battuta devotes special attention to the caravan’s guards, guides, and camel-drivers. They were all Berber nomads of the Masufa tribe. If you hired the Masufa, you were (theoretically) under their protection. If you didn’t hire them and bumped into them as they camped along the trade routes, you were fair game for robbery. It was a protection racket, and if you wanted to venture south from Sijilmasa, you had to pay into it. Not that paying off the tribe was enough – you still had to bribe individual guards not to steal from you.

There were plenty of other hazards too. Obviously, you had the heat, the thirst, and the fetid, poisonous desert water. Ibn Battuta reports mischievous djinn that will try to get you turned around. And getting separated from the caravan could be deadly! Merchants would often entertain themselves on the trip by going off to hunt antelope or riding a bit ahead of the column. But it’s easy to lose sight of the caravan behind a line of bluffs. On Ibn Battuta’s trip, a man named Ibn Adi argued with his cousin, and fell behind the caravan in a huff. When Ibn Adi didn’t arrive in camp that day, Ibn Battuta urged the cousin to pay the Masufa to search for him. The cousin refused, and Ibn Adi was never seen again.

In your fictional campaign setting, if you combine the perils Ibn Battuta describes with a trip to find a treasure based on the Ma’adin Ijafen, the adventure gets a lot more interesting. And it really takes on a life of its own if you have to deal with folks like the Masufa! You have to protect your treasure from your own guards, and when you arrive at the wreck, they may suddenly demand a cut. Is it worth stopping to negotiate when you only have enough water for a few hours of heavy labor digging up the treasure? Throw in a desert monster attacking at the worst possible moment, and now you’ve got yourself a treasure hunt!

–

Source: The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages, by François-Xavier Fauvelle (2018)