A good RPG villain often epitomizes the worst aspects of the game’s setting. For a campaign set in a big city, those might be crushing poverty or a rigged justice system. A good villain, then, might be a powerful person willing to take advantage of both. For your urban campaigns – Blades in the Dark, Harlem Unbound, Urban Shadows, Spire, etc. – I present to you a particularly nasty figure from Dickensian London: Theobald Meyrick.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

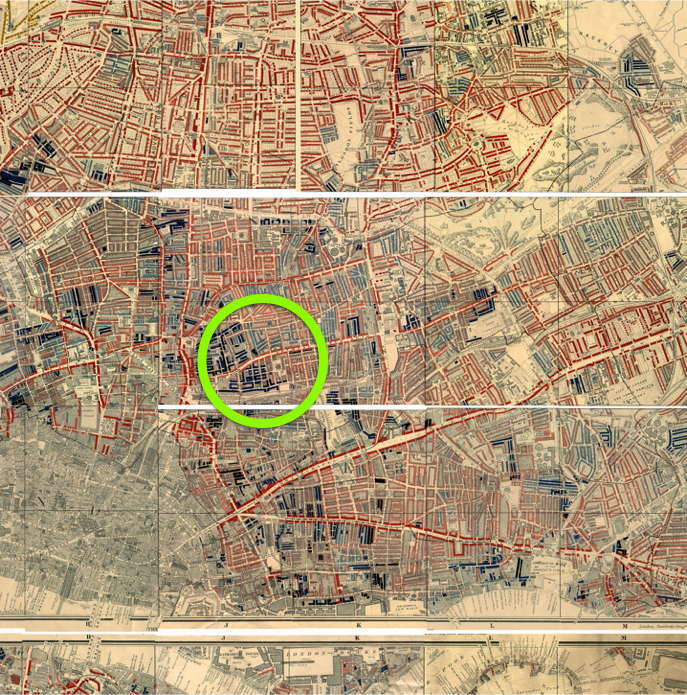

Meyrick operated the workhouse in the Bethnal Green region of East London in the 1860s. A workhouse was a place the desperately poor could go for alms in exchange for doing meaningless ‘make-work’ like breaking stones or unraveling old rope. A workhouse would pay you, feed you, and give you a place to sleep, but conditions were intentionally harsh: only marginally better than living on the street. This was to discourage people from living on public assistance unless they had absolutely no choice. The famously impoverished and overcrowded East End of London had some of the nastiest workhouses in England. Worse, the Poor Laws dictated that each community financed its own workhouse, so the most-used workhouses were in places that could least afford them: places like Bethnal Green.

You might introduce an NPC based on Theobald Meyrick with an incident based on an 1863 formal complaint to the workhouse Board of Guardians by 142 aged and infirm workhouse inmates. They’d been set to picking apart old rope. If they didn’t pick apart a given amount in a given time, Meyrick would cut their rations and wouldn’t let them out of the workhouse on Sundays. Meyrick denied he’d given such an order, and that anyway the old people enjoyed picking apart rope. (“I didn’t do it, and if I did, you’re lying about how you feel about it.”) The Board of Guardians sided with Meyrick. What others might see as elder abuse, the Guardians saw as a way to dissuade the poor from entering the workhouse. This kept taxes low and let Meyrick and the Guardians pocket any leftover funds.

Another incident you can stick anywhere is the death of George Harries. Harries was working in Hackney when he collapsed. His fellow workers flagged down a passing cart and rushed him to the nearest hospital, which was at Meyrick’s Bethnal Green workhouse. The attendant on duty at the workhouse tried to turn Harries away, arguing he should have been taken to the Hackney workhouse, even though the Bethnal Green workhouse was actually closer. After twenty minutes, the attendant grudgingly summoned the hospital’s physician who pronounced Harries dead. At the coroner’s inquest, the physician reported that had he been summoned immediately, Harries would likely have lived. Meyrick was probably not the attendant on duty, but the whole mess is indicative of how he ran his workhouse: petty, cruel, and bone-headed. PCs who investigate a fictional version of the situation may even find the attendant was following Meyrick’s direct orders.

(Trigger warning: rape)

But Meyrick really came into public prominence after he raped one of the women in his workhouse. Sarah Ann Smith was seventeen when she was admitted for a few weeks. Nine months later, she bore a child. She accused Meyrick of luring her into his office, locking the door, and raping her. There was a trial. The tactics used to discredit Smith’s testimony would seem familiar in a modern setting. She didn’t scream enough or put up enough of a fight. She had sex with other people in the workhouse. Most of these claims didn’t stand up to cross-examination, and none of them were material to the question of whether Meyrick was guilty of rape.

The prosecution put up excellent evidence. Smith testified to what she went through. Meyrick didn’t deny the child was his. Meyrick’s friends paid Smith off to keep her quiet. Meyrick offered fifty pounds to the master of another workhouse to have Smith killed. Various employees of the workhouse were seen assuming false identities to try to talk to Smith.

Despite this evidence, the court ruled that the charges against Meyrick were unsubstantiated. More remarkable still, the workhouse’s Board of Guardians didn’t fire him. If Theobald Meyrick didn’t rape Sarah Ann Smith (which he definitely did), then fathering a child on her and paying her money certainly meant he was running his workhouse like a brothel. But in Britain in 1862, only the well-off were enfranchised. And the few people in Bethnal Green wealthy enough to vote were bar owners, shopkeepers, and merchants who were glad Meyrick ran his workhouse badly, because it meant they had to pay few taxes to maintain it.

If your PCs are going up against a well-connected villain like Meyrick, they may seek the help of an influential patron. Enter Baroness Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814-1906). The heir to a large banking fortune, she devoted considerable efforts to philanthropy in Bethnal Green. During the 1866 cholera epidemic, she traveled throughout East London personally distributing thousands of free meal tickets, at her expense. In 1864, she constructed a huge, ornate public building – a palace, really– to serve as a vegetable market in Bethnal Green. Like many modern food deserts, East Enders had little ready access to fresh fruits and vegetables. Produce distributors never accepted the market and it failed to be viable, but the palace certainly showcases the Baroness’ commitment. If the PCs are going after a villain based on Meyrick, a patron based on Baroness Burdett-Coutts could be a big help.

Even if you’re not running an urban campaign, Meyrick offers a lesson in villain design. He exploits and thrives on the worst parts of the world in which he lives. He doesn’t just do evil. He uses the evilest aspects of his world to do evil, doubling down on the wickedness and maintaining thematic consistency. Real campaigns can be notoriously unfocused in tone and message. Thematic consistency (with a little help from your villain) is the sort of thing can elevate a good campaign to a great one.

–

Sources:

London’s East End: Point of Arrival by Chaim Bermant (1975)

Inhumanity at Bethnal Green Workhouse, East London Observer, 22 AUG 1863, page 3