It was 1695 in Surat, a large seaport city in what is today northwest India and was at the time the Mughal Empire. Every year, ships from Surat sailed west across the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea. They carried goods to trade in Yemen and Muslim pilgrims on the hajj: the pilgrimage to Mecca every Muslim healthy and wealthy enough must undertake at least once a lifetime. Now it was September and the ships were returning, carrying homeward-bound pilgrims and rich cargo. But when one of the ships arrived late, bearing news it was attacked and robbed by British pirates, it would set off months of unrest in Surat and set in motion events that would change India forever. This unrest and its knock-on effects make an incredible template for an RPG adventure.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

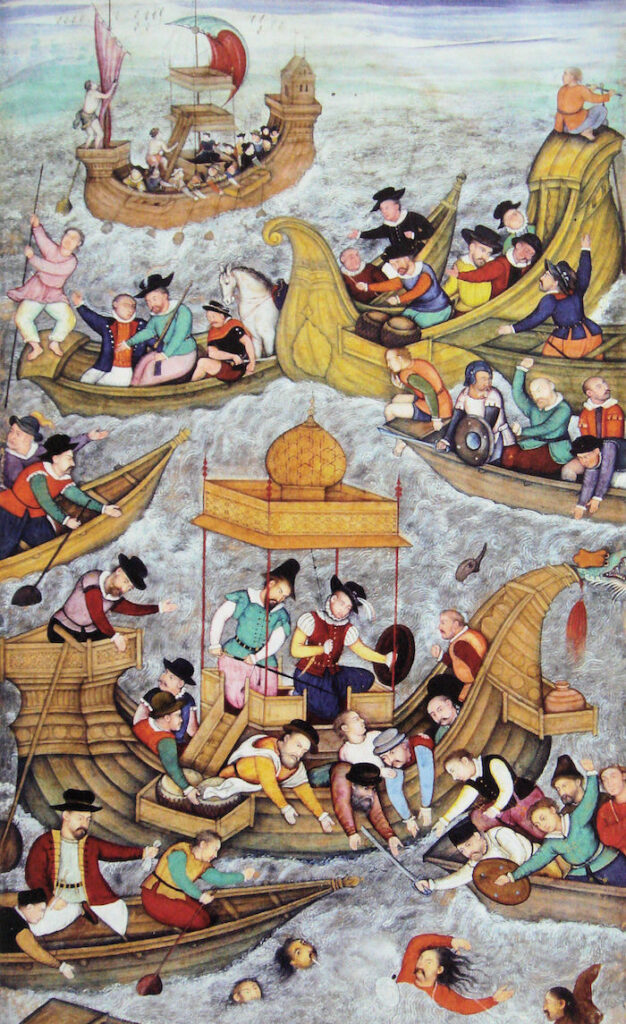

The ship that arrived in Surat, the Fath Muhammad, was a 200-300 ton cargo ship carrying six guns. She was part of a larger convoy of ships, but had gotten separated. When she was attacked by four British pirate vessels – the Pearl, the Portsmouth Adventure, the Susanna, and the Fancy under command of the flotilla’s leader, Captain Henry Every (we’ve discussed Every and the Fancy before), her captain decided against valor. The ship fired three shots and struck her colors. The pirates found the Fath Muhammad had a rich cargo: silver and gold equivalent to $5 million today. The pirates divvied up the loot and went looking for the rest of the convoy. Remarkably, they did not sink the Fath Muhammad. They’d killed a few Indian sailors in taking the ship and probably tortured a few more. The pirates let the survivors limp on to Surat. That meant when the Fath Muhammad arrived in port, full of holes and riding too high in the water, there were plenty of witnesses to tell the tale of a British flotilla that murdered, tortured, and robbed them.

The people of Surat knew the British. The British East India Trading Company had an outpost there. This outpost (called a ‘factory’, because it’s where a factor worked) was a walled compound with offices, warehouses, and residential dormitories. In 1695, the East India Company wasn’t yet the tyrannical juggernaut we think of. It was a giant company and immensely wealthy. But it exerted little sway over the Mughal Empire and wasn’t even that impressive in comparison. By some estimates, the owner of the Fath Muhammad, Abdul Ghaffar, did trade equal to the whole of the East India Company on his own. And while we would distinguish between the East India Company, the British government, and pirates who happened to be British, much of Surat was unconvinced these distinctions were meaningful.

Things got messy quickly. Abdul Ghaffar publicly claimed the East India Company was secretly allied with the pirates and splitting the profits. A mob gathered at the gates of the factory. The chief factor, Samuel Annesley, ordered the gates to the factory closed. He figured he could just wait this out; it wasn’t like the mob outside could breach the walls. But then the head of the Mughal army in Surat, Usher Beg, arrived at the gates at the head of a column of cavalry. He shouted up to Annesley that he had a secret message from the Mughal governor of Surat, and Annesley let him in. It was a trick. Actually, Usher Beg was there to take over the compound and place the employees under house arrest in their rooms. Annesley did the smart thing and complied.

In the crowd outside the factory was an important figure in this story: Khafi Khan, special envoy of the Grand Mughal (the emperor). He was a sort of traveling court reporter. His job was to go wherever the Grand Mughal sent him, learn everything relevant about what was going on, and write back to the Grand Mughal with his observations and recommendations. Khafi Khan interviewed the Fath Muhammad survivors. He circulated among the people gathered outside the factory and documented their concerns. He was somewhere between a journalist, a historian, and a spy – and we have his documents! Complicating the situation, Khafi Khan’s writings are controversial today: often biased, sometimes plagiarized, and sometimes even wholly fictitious.

With the British arrested, the agitators changed targets. A protest now began outside the mansion of the Mughal governor, I’timad Khan. The protestors demanded the governor execute the British imprisoned in the factory. I’timad Khan cleverly played for time. He promised to convey the facts of the case to the Grand Mughal in Delhi, then do whatever the Grand Mughal ordered. Of course, it would take weeks for a message to be carried round-trip. Hopefully by then the situation would have blown over.

That wouldn’t happen. Only two days later, another ship dropped anchor in Surat after having been attacked by the same pirates. And this attack was far, far worse. This was the Ganj-i-Sawai, a 1,500-ton treasure ship owned by the Grand Mughal himself. She was built to turn a profit for the emperor and to carry members of his court on the hajj to Mecca in fine style. She should have been able to shrug off any pirate in the world: she was six times the size of the Fath Muhammad and guarded with eighty cannons and four hundred soldiers. But the survivors that streamed from her decks told stories of incredible bad luck. A shot from the pirate happened to topple the Ganj-i-Sawai’s mainmast, leaving her unable to maneuver. When the Indian ship went to fire back, one of her cannons exploded, sweeping her gun deck with lethal shrapnel. Then her captain panicked and fled belowdecks instead of organizing his enormous marine guard to repel the comparatively small boarding party.

cw: rape

The pirates seized the ship’s almost unimaginably vast treasure, worth $200 million to $800 million today, all of it the personal property of the Grand Mughal. They tortured the crew to force them to reveal secret compartments concealing the choicest items. And the passengers – 800 religious pilgrims from the Mughal court, many of them women, including a granddaughter of the Grand Mughal – were subjected to a multi-day gang rape. Many jumped overboard to drown as an escape. And the final detail the Ganj-i-Sawai survivors revealed was this: some of the pirates told the crew that their attack was revenge for wrongs the East India Trading Company had suffered in Bombay.

We don’t know whether any of the pirate crew were former Company employees who may have been in Bombay when the Mughals besieged the factory there five years earlier. The pirates might just have heard of the siege thirdhand. Claims of revenge might just have been “Remember the Maine!” three centuries too soon. Regardless, in Surat, all distinction between pirate and Company vanished. Abdul Ghaffar, owner of the Fath Muhammad, joined with Surat’s Muslim clerics to whip up the crowd and demand action. Governor I’timad Khan stood by his pledge not to execute anybody until he heard from Delhi. But in the interim he ordered every Englishman in Surat, regardless of their affiliation with the Company, chained and properly imprisoned in the factory – no more polite house arrest.

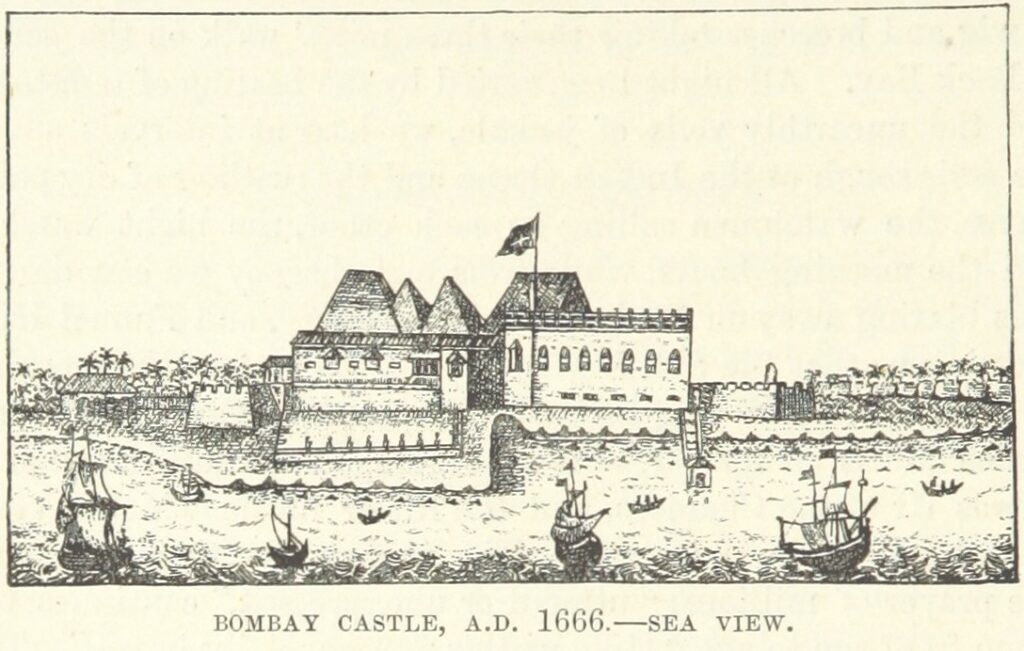

Through all this, Khafi Khan (the eyes and ears of the Grand Mughal) interviewed and documented. It’s thanks to his (often unreliable) work that we still have eyewitness accounts from Ganj-i-Sawai survivors. He eventually wrapped up his time in Surat and continued south along the coast on other business. He came to Bombay, where the East India Company maintained its headquarters on the subcontinent: the Bombay Castle. The British in Bombay were not under arrest, but only because they’d barricaded themselves in the castle, awaiting the inevitable siege. A contact of Khafi Khan’s was friends with John Gayer, the head of the Company in India. Gayer tried to use this connection to defuse an escalating situation that threatened to expel the British from the Mughal Empire.

Khafi Khan and John Gayer met in the Bombay Castle. The Mughal agent laid out the facts of the case. Gayer tried to explain away the revenge claims, saying that those pirates must surely have been former Company employees, not current ones. Khafi Khan conceded the possibility. But that was a pretty slender thread for the Company to hang on, particularly when they’d routinely acted in bad faith in the past. Most notably, the Company minted coins in Bombay, which was a privilege the Mughal government reserved for itself. And the current Grand Mughal, Aurangzeb, tolerated no challenges to his authority. The Company would have to do a lot more than apologize if it didn’t want to be expelled from India.

Ultimately, the Grand Mughal and the Company came to an agreement. First, the British government, working closely with the East India Company, caught eight of the pirates, convicted six, and hanged five of them. This was a good-faith gesture to demonstrate the Company was not working with pirates. More importantly, the Company assumed counter-piracy responsibilities in the Indian Ocean. The Mughals already had a system of bandit hunters that patrolled the roads to keep them safe. The Company adopted the same role on the high seas. To the Grand Mughal, this was a great deal. The Golden Age of Piracy began within a few decades, but it plagued the Caribbean, not the Indian Ocean, thanks to the Company’s patrols – which cost the Mughals not a dime! Nine months after the pirate attacks on the Ganj-i-Sawai and the Fath Muhammad, the factory in Surat re-opened.

In the long term, this deal fundamentally changed the role of the Company in India. This was the first time the Company assumed governmental authority. In acting as counter-pirate patrollers, they became agents of the state. Out at sea, the Company was the state. More substantive changes in the nature of the Company wouldn’t come for sixty more years when Company employees conquered Bengal and began ruling it directly, but the groundwork was laid in the compromise agreed to in 1696.

At your table, this business isn’t an adventure. It’s a setting. Run the adventure you were going to run anyway: find the kidnapped child, avenge your mother’s death, heist the jewels, blackmail the governor, whatever. This setting lets you keep the ‘spine’ of the adventure relatively straightforward, but have the setting present obstacles at every turn. Need to talk to an NPC? She’s under house arrest in the factory, or hunkering down in the closed-off governor’s mansion, or very busy organizing high-level diplomatic talks. Chasing someone? They cross the street just ahead of an angry mob that you now have to push through. The situation gotten too quiet? Another ship (or caravan or whatever) shows up claiming even worse depredations, stirring up the hornet’s nest all over again. And there’s this royal envoy (based on Khafi Khan) who’s sniffing into everything unusual, including what the party’s up to. He’s good at his job too. If you’re up to any funny business, he’ll find out and report it to the government.

Naturally, having the PCs doing things in this charged environment will probably change the course of events. How they behave may wind up having a big impact on your setting, even if they didn’t mean to.

You can put this adventure location in any port or crossroads in your setting that’s not a capital city. Because so much of the tension comes from the Company’s comparative powerlessness, it doesn’t matter if your setting doesn’t have a pre-established mercantile empire or colonial power. Just invent a moderately-successful trading house and have it fill the role of the Company. Note that it’s important your analogue of the Grand Mughal isn’t in the same city as the factory, since it lets the situation develop over time. I would also collapse Bombay and Surat into a single location. From a gaming perspective, there’s little to be gained from putting the trading house’s headquarters in a different city from the epicenter of the conflict.

Finishing grad school while working a day job continues to kick my butt, but the end is in sight! Classes end in a month and a half. I could not be more glad. Writing blog posts has taken a back seat; I’ve completed only one post this semester. Still, that’s why I maintain a robust buffer of pre-written blog posts. I expect to end the semester with two months of buffer remaining, which is perfectly manageable. As before, my Master’s will be in Geographic Information Systems (GIS, fancy computer maps), so if you happen to have a hook-up for GIS jobs in St. Louis, Minneapolis, or 100% remote, please don’t hesitate to let me know via the ‘contact’ feature at the top of the page.

One element of the blog work has not stopped, though: the new site! Steve Radabaugh of Radical Bomb Technology (and RPG designer by night) is hard at work on a new version of the Molten Sulfur Blog. It’s cleaner, tighter, more readable, and – most excitingly for me – is searchable and filterable. I want it to be easy for you to find the perfect content for your game tonight. My ambition is for the Molten Sulfur Blog to be the first place you go when you’re not sure what your players are going to run into next session. Making it easy to find that material is a necessary step.

Finally, it’s spring! I’ve been getting my plot ready in the community garden. Last weekend, I transplanted my seedlings to bigger pots (read: red Solo cups) and am excited to put them in the ground once the last frost passes.

As always, writing this blog is a great joy. Thank you so much for reading!

Source: Enemy of All Mankind: a True Story of Piracy, Power, and History’s First Global Manhunt by Steven Johnson (2020)