Shanty Hunters, my upcoming RPG about collecting magical sea shanties in 1880, goes live on Kickstarter on November 2nd. (So close!) This week on the blog, I’d like to offer a sneak peek: an excerpt about three ports in 1880 (the book has twenty) and another historical shanty from the shanty songbook. Last month, we peeked at some information about sailors. In August, we saw an excerpt about the sea. In July, it was the book’s first five pages. To learn more about Shanty Hunters and be notified when the Kickstarter launches, follow this link!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Shanghai

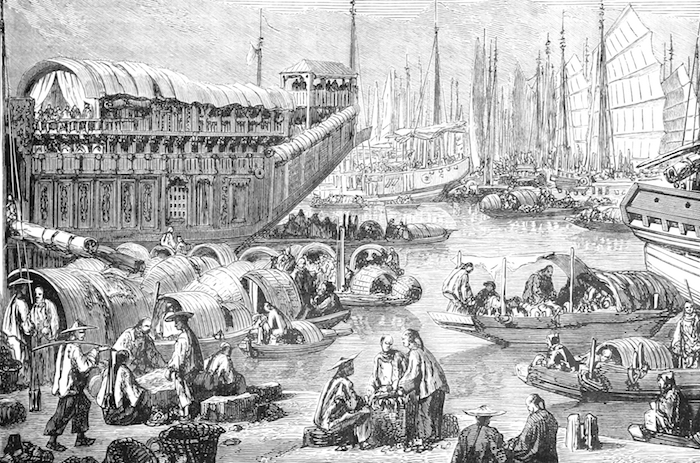

Shanghai is China’s biggest international port. It is located near, but not at, the mouth of the great Yangtze River. To reach it by ship, one must first sail 25 miles up the Yangtze to its tributary, the Huangpu River. Pass under the guns of the Chinese fort and its red-painted war junks, then sail twelve miles up the Huangpu to reach Shanghai. The whole area around the city is part of the flat, heavily-farmed alluvial plain of the Yangtze delta and is riven with ever-smaller rivers flowing into one another and eventually into the East China Sea.

In downtown Shanghai, merchant vessels lie at anchor in the muddy brown waters of the Huangpu. A great many of them are junks, the characteristic Chinese sailing vessel. Other vessels are sampans: small, flat boats with an awning in the middle. The sampans serve as fishing boats, water taxis, light transport, and homes for their operators.

Half of the port section of Shanghai (the part on the west bank of the Huangpu) falls in the ‘Shanghai International Settlement’. Foreign powers (especially the British) forced the Chinese government to cede this section of the city to their control following a sequence of raids and wars. The Chinese are less than thrilled about this foreign occupation, but there’s little they can do about it. There’s a separate French concession in Shanghai too, and China retains the rest, including the old walled city just upstream of the French concession. The Chinese section is particularly cut through with intersecting creeks and canals, all criss-crossed by bridges.

The heart of the International Settlement is the ‘Bund’, which is full of grand European-style buildings and the homes of wealthy Western merchants. Shanghai has many European and American residents. They have built their section of the city to their preferences, complete with a theater, cathedral, consulates, and a sailors’ home.

The half of the port on the east bank of the Huangpu is outside the International Settlement. It is open to trade from all nations, including China herself. China’s foreign trade is rapidly passing into her own hands. Already, the Chinese-owned China Merchants’ Steam Navigation Company is as large as Japan’s own Mitsubishi shipping company.

Because of the confused international situation in the city, Shanghai has fourteen different consular courts, plus the Chinese court and a ‘mixed’ court. None have clear legal jurisdiction or the resources to enforce their decisions. This contradictory mish-mash of governmental authorities is convenient for any foreign sailor who wants to get up to some caper (drunken or otherwise) and escape prosecution. If you want to run a chaotic port-based adventure, Shanghai is the place to do it.

Two thirds of Chinese foreign trade flows through Shanghai. The primary import from the West is opium, a dangerous drug that foreign merchants have managed to get Chinese consumers hooked on. Also important at Shanghai are cotton and metal – the latter for a gun factory just upstream. Shanghai’s chief export is silk, followed by tea.

Kingston

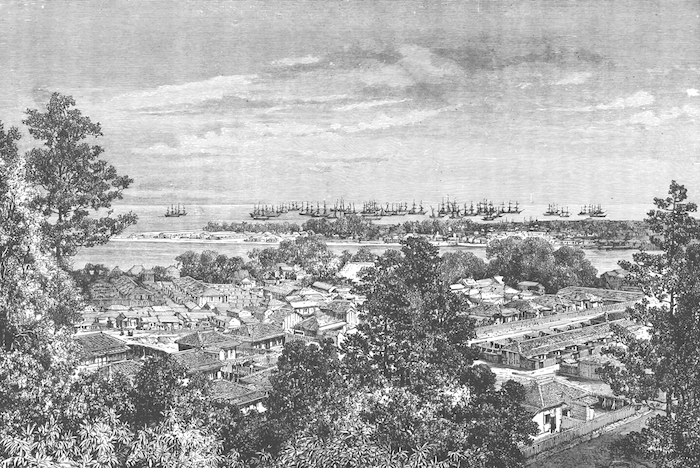

Kingston lies on the south coast of Jamaica beneath verdant peaks. A long, thin spit of rocky land (the ‘Palisadoes’) parallels the coast, acting as a natural breakwater for Kingston harbor. The harbor is sizable and protected in almost every direction from stormy swells. At the tip of the spit are two forts and the village of Port Royal. It was once the largest European settlement in the Caribbean. In the 17th century, Port Royal was a notorious ‘pirate utopia’, but in 1693, a devastating earthquake flattened the town. The survivors fled across the bay and founded Kingston.

In 1880, Kingston is a British colony. For the colonial elite – officers, businessmen, and government officials – there are billiard rooms, bowling alleys, reading rooms, verandas, and parks for cricket matches. Their fine villas dot the bright green scrub outside of town. For the common people, there are wooden houses of very irregular styles – large and small, well-kept and dilapidated all mixed together. The city burns every so often, yet there is no fire brigade. The majority of Kingston’s citizens are black, either freedmen or the descendants of freedman. Slavery only ended here in 1834. Most ordinary farmers grow sugar, yams, and plantains, just as they did before emancipation. Laborers are also being imported from India to work in the new coffee plantations.

Kingston’s primary dockyards remain in Port Royal. The village is still a sink for vice, full of taverns and brothels and rotting buildings. Making the three-mile trip across the bay to Kingston proper is done by small boat. The harbor is busy, full of little sailboats with high cotton sails trading with Her Majesty’s warships.

Jamaica’s pirate past remains very much in the popular consciousness of her inhabitants. Pirate treasure – hidden in caves and buried on nearby islands – is an accepted part of local folklore. Gullible sailors may be taken for a ride by some enterprising local promising to guide them to just such a cache. The better guides are just scamming their victims for tips. The worst ones lead their marks into a robber’s ambush.

Merchant ships arriving in Kingston are likely to bring salt fish and manufactured goods. They invariably leave with their holds full of sugar. It’s common for merchant ships homeported in the West Indies to have a ‘checkerboard crew’ – one watch white, one watch black.

Yokohama

Yokohama is Japan’s primary international port. It lies on the south shore of Tokyo Bay, fifteen miles down the coast from the capital. Low hills covered in dark fir trees surround the town, and mists linger in the valleys between them. When not obscured by clouds, the distant cone of snowcapped Mount Fuji punctuates the landscape. European-style buildings line the shore and bluffs. Farther inland, the style is unambiguously Japanese, with wooden buildings and clay roof tiles.

The port is bustling, full of ships both foreign and domestic. Japanese-built steam launches scurry between the anchored merchants and warships. Steamships from the Mitsubishi company come and go with cargoes of mail for ports around the country and the mainland. Fishing boats ply the bay, distinguished by their high bows and sterns (like crescent moons) and the large owner’s mark on each boat’s square sail.

The port of Yokohama is the product of Japan’s tumultuous recent history. The country had been ruled by a military dictatorship that cut off access to the outside world. In 1853, an American flotilla dropped anchor in Tokyo Bay and threatened to attack Japan if the country did not open its ports to foreign trade. The government reluctantly acquiesced, and turned the small fishing village of Yokohama into a major port. Faced with this and other systemic shocks, the military dictatorship soon crumbled. Though the role of the emperor had been ceremonial for centuries, in 1868, the emperor Meiji assumed control of Japan. He began a robust policy of westernization and modernization to ensure such a disaster could not reoccur.

Twelve years later, the process of modernization is on full display in Yokohama. Gas-powered street lamps line the avenues. Vendors hawk Japanese newspapers. Trains chuff along between the port and the capital along Japan’s first railway. Telegraph lines hang overhead and the streets are full of rickshaws (only invented a few years ago). Still, the architecture remains unambiguously Japanese, as does the local clothing, despite the emperor’s attempts to introduce western costume.

Common sailors are forbidden to leave the port town. Prestigious and wealthy foreigners are granted special exemptions and may even have homes in Tokyo, but ordinary foreigners may go no farther than the moat that rings Yokohama. Merchant John has little chance of attending a tea ceremony or visiting a Buddhist temple or Shinto shrine. He must content himself with drinking rice wine in European-style bars and brothels – and perhaps get a tattoo! The emperor recently outlawed Japan’s ornate tattooing tradition. In response, some artists went to Yokohama to work their trade on the only legal subjects remaining: foreign sailors. Tattoos are little-known in the West, so a colorful Japanese masterpiece is the mark of a great traveler.

Yokohama’s appetite for imports is voracious. Japan needs manufactured goods by the boatload to modernize: goods like steel, glass, cloth, cement, household goods like lamps – and the machinery to start producing them all domestically. Ships that arrive in Yokohama carrying these goods leave for Europe or North America laden down with silk, tea, and art objects. Ships bound for China leave with holds of copper, coal, and preserved seafood.

Sacramento

Suggested cover: Sacramento by the Dreadnoughts on the album Into the North (2019).

Oh, around Cape Horn(1) we are bound to go

Response: To me hoo-dah! To me hoo-dah!

Around Cape Horn through the sleet and snow

Response: To me hoo-dah, hoo-dah day!

Chorus:

Blow, boys, blow, for Californ-eye-o!

There’s plenty of gold(2), so I’ve been told

On the banks of the Sacramento(3)

Oh, around Cape Horn with a mainskys’l(4) set

Response

Around Cape Horn and we’re wringing all wet

Response

Chorus

Oh, around Cape Horn in the month of May

Oh, around Cape Horn is a very long way

Them Spanish gals ain’t got no combs

They comb their locks with tummy-fish bones

Sing and heave and heave and sing

Sing and make those handspikes(5) spring

Breast your bars and bend your backs

Heave and make your spare ribs crack

Santander Jim is a mate from Hell

With fists of iron and feet as well

We’ll crack it on, on a big skiyoot(6)

Ol’ Bully Jim is a bloody big brute

Oh, a bully(7) ship with a bully crew

But the mate is a bastard through and through

‘Round the Horn and up to the Linev(8)

We’re the bullies for to make her(9) shine

1: The southern tip of South America.

2: ‘Plenty of grass to wipe your ass’ is also a common line here.

3: A river in northern California whose mouth is at San Francisco Bay.

4: On the middle mast, the fifth sail up from the deck.

5: The bars inserted into the capstan that the sailors heave on to bring the capstan around.

6: This reference is lost.

7: ‘Bully’ is a shifty word in the sailor’s lingo. It usually means ‘tough’, but it can equally mean ‘tough and excellent’ or ‘tough and cruel’. Which meaning is intended is often contextual.

8: The equator.

9: The ship. Ships are always female in English.