In 1870, the government of China had to send an emergency legation to Paris in response to an incident in a Chinese port. It was an unusual circumstance; this was only the third formal diplomatic mission sent by the Qing dynasty to the Western world. A translator with the 1870 mission, Zhang Deyi, had served on both of the previous missions and should have found this one routine. Instead, when the party reached Paris, they found a city devastated. The French government had been overthrown, and Paris itself was about to go into open rebellion against this new government. It wound up being a year of truly historic chaos in France, and Zhang Deyi had a front-row seat for all of it. It’s a remarkable story, and it’s a great template for some interstitial tissue in your ongoing RPG campaign: a cool way to move your party from one adventure to the next.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

The 19th century was bad for China. Western nations waged a series of wars against it, all of which China lost, resulting in these foreign powers forcing humiliating (and expensive) concessions upon the Chinese state. Simultaneously, a series of internal rebellions were arguably even more devastating. The Imperial government of China’s Qing dynasty worked hard to adapt to changing circumstances, but was only partially successful. Part of the issue was that, though China had been a regular trade partner with the Western world for centuries, the Qing government didn’t actually know much about that world. Yixin, the Qing regent from 1861 to 1865, wrote that “Foreigners know everything about us, but we do not know anything about them.” There was no shortage of Chinese traders, sailors, and emigrants who were intimately familiar with the West, but little of their knowledge was available to government officials. To remedy this situation, the Qing government established a formal ministry for the management of external affairs and a school for government translators. The hope was that these institutions would be able to staff fact-finding missions to the Western world that could bring home information to better guide government policy.

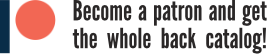

In 1866, these institutions got their first chance. Robert Hart, an Englishman employed in the Chinese government as the head of the Maritime Customs Service, announced he was going to take a trip back to England to visit family. He’d be happy to take a legation with him and act as chaperone if they’d like. This was China’s first official diplomatic mission to the Western world. It was a moderate success! The legation was feted by the crowned heads of Europe, shown about the continent, and generally permitted to see whatever the envoys wanted to see. Friendships were forged, intelligence was gathered, and everyone went back home to China. One of the translators on this trip was a young Zhang Deyi, who’ll be relevant again later.

In 1868, China launched its second Western legation, this one to America and then on to Europe. This mission was prompted by the scheduled renegotiation of one of the onerous treaties China was laboring under. The hope was that by going abroad to renegotiate, China’s diplomats might be able to secure better terms. This mission too accompanied a Westerner, Anson Burlingame, the U.S. ambassador to China. But Burlingame died of pneumonia shortly into the trip, thereby demonstrating that the envoys didn’t really need a chaperone. Zhang Deyi was a translator on this trip too, though he fell ill and had to go home early.

In 1870, there was a riot in the port of Tianjin. Anti-foreign sentiment was running high. This whole period would later be termed ‘The Century of Humiliation’; lots of people were angry. Spurred on by false rumors that Europeans were murdering Chinese children, rioters killed fourteen Europeans, including the French consul. (If you’re getting pizzagate or blood libel vibes, so am I.) If France was looking for an excuse to start a war with China, this would do. And the Qing government knew how that would go: France would win, China would have to sign yet another treaty giving up still more autonomy and wealth, and it would only exacerbate China’s more serious internal problems.

To head off a possible war, the government threw together an emergency legation to France. This mission would travel to Paris, apologize profusely, promise that China would do a better job in the future, and hopefully save the day. Of course, most of the (very few) experienced diplomats China possessed were still overseas with the 1868 mission. So to head the mission, the government tapped a man named Chonghou, the commissioner of ports whose bad handling of local tensions was partly responsible for the riots. Hopefully his personal apology would make the legation’s arguments more convincing. To show France how serious China was, Chonghou was given a brevet (temporary) promotion to the highest rank in the Chinese civil service. This reward was leavened with punishment, though. Chonghou would foot the bill for the whole mission.

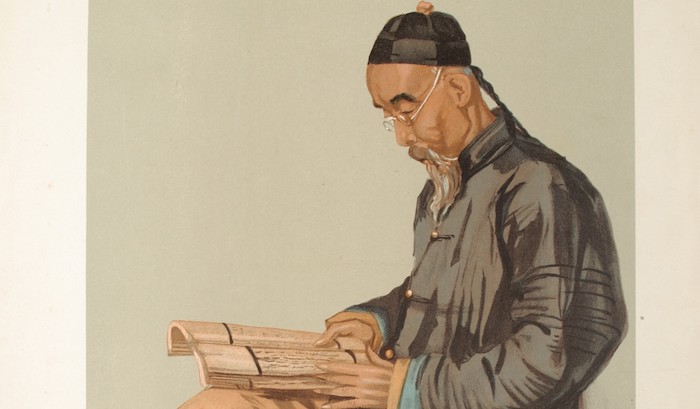

For the position of head translator, the only person available was Zhang Deyi, home early from the 1868 mission. He was only twenty-four years old, but to reflect his experience, he was promoted to the brevet position of Vice Director of the Ministry of War. The young translator was an interesting fellow. He came from a poor but well-connected family (a Han banner family, if you know what that is), attended a charity school, joined the brand-spanking-new ministry for the management of foreign affairs, and immediately proved himself a whiz at languages. He was tapped for inclusion in the first overseas mission almost as soon as he passed his language exams. Zhang found the Western world endlessly fascinating. His writings are full of little minutiae, like the rules of foreign games and sports. He deeply believed that Chinese and foreigners were not so different, and sought to highlight the similarities between cultures to audiences both foreign and domestic. He would go on to a long career in the diplomatic service.

The legation got under way with enormous pomp, the better to reflect how Very Serious the government’s apology was to anyone who might report back to France. But when Zhang, Chonghou, and the other civil servants reached Paris, they found that a dead French consul in Tianjin was just about the last thing on France’s mind.

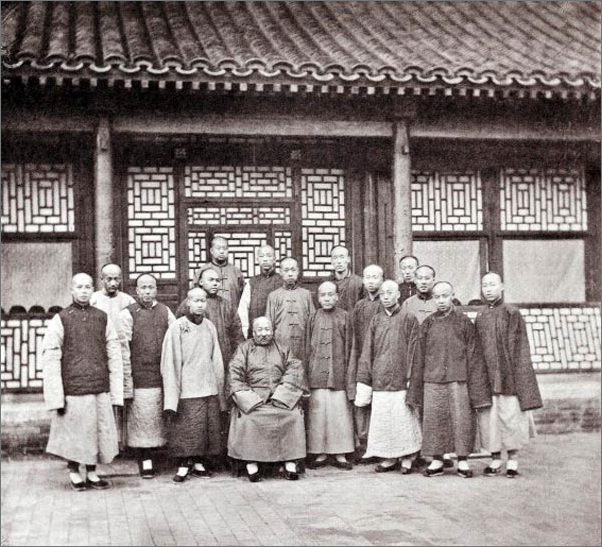

While Zhang and Chonghou were at sea, France launched a war against Prussia (Germany). It went very badly. Two months after war was declared, everything collapsed. The French emperor Napoleon III (also called Louis-Napoleon, the nephew of the more famous Napoleon who usually doesn’t have to be called Napoleon I) was captured while leading his troops on the battlefield. Pretty much the whole French army was either captured or bottled up such that it couldn’t do anything. As Prussian troops laid siege to Paris, the remnants of the French government declared the Second French Empire over and announced the formation of the Third French Republic. Due to the extreme situation France found itself in, this ostensible republic’s first president was a military general appointed (not elected) by the guys who seemed to be most in charge at the time. This general negotiated a French surrender, which calmed things down enough for elections to be held. The new president, Adolphe Thiers, then had the unenviable task of negotiating the withdrawal of the Prussian army from France, which would prove enormously expensive.

This was the situation Zhang and Chonghou found when they arrived. They managed to track down Count Michel Alexandre Kleczkowski, a sinologist who was ostensibly the French government’s guy in charge of Chinese affairs. The count doesn’t seem to have had any actual power, and mostly tried (unsuccessfully) to keep the Chinese legation from seeing how utterly destitute the war had left France. Zhang records walking through streets full of paupers, seeing whole families living in caves, and lamenting that the grand city of Paris he’d visited before had been reduced to squalor. Chonghou, the head diplomat, spent his time as much like a gentleman as he could. He traveled the countryside, visited parks, went for boat rides, and attended the opera. The Chinese legation would have to wait a full year before Adolphe Thiers found time to receive them.

And it would be an important year! The elected government of the Third Republic was pretty conservative. It initially favored installing a constitutional monarch and agreed to absolutely punishing payments to Prussia to get the Prussian army out of France. Meanwhile, the city of Paris skewed left-wing and was moving further left by the day. During its four-month siege, the city was totally cut off from unoccupied France and reduced to starvation. People ate the animals in the zoo, then moved on to rats and mice. When the war ended, the devastation left behind meant the people of Paris were little better off. And all the Third Republic’s money going to Prussia meant that Parisians had little hope their situation would improve. Complicating matters, Paris had its own army. The National Guard (a sort of militia) was poorly-equipped and undisciplined, but it was big. And a lot of its units were even further to the left politically than the citizenry of Paris. Every strain of leftist or radical thought was represented in at least one of the neighborhood brigades of the National Guard, and they all hated the conservative government that was leaving Paris to rot and starve. The government itself actually ruled not from Paris but from nearby Versailles, where it felt safer.

In March of 1871, the Third Republic tried to partially disarm the National Guard, and the Guard rose in open rebellion. They declared a rival government to the Third Republic: the Paris Commune. For two months, Paris was effectively its own state. The Paris Commune held its own elections and began to provide its own government services. It was an extraordinarily chaotic business, with many, many ideological factions fighting it out for control, both at the ballot box and at the executioner’s block. The Third Republic was terrified that the Commune would expand its control beyond Paris. It scrambled to organize an army of its own, mostly composed of ex-POWs returning from Prussia. After two months, the Third Republic invaded Paris and bloodily crushed the revolt. What the Paris Commune might have become if given time to consolidate beyond its messy and semi-spontaneous origins has been a subject for speculation ever since. There’s even an RPG about doomed revolutionaries in the Paris Commune! Red Carnations on a Black Grave is generally well-regarded, though I’ve not read or played it, so I can’t speak to it myself.

The translator Zhang Deyi was at least partially an eyewitness to these events. He recorded what he saw in his diary and in a later unpublished manuscript. Like every commentator on the Paris Commune, he viewed it through his own ideological lens. To Zhang, the chaos that followed the Franco-Prussian War was a Confucian dynastic struggle. Both Emperor Napoleon III and President Thiel were corrupt and unjust, and thus had run afoul of immutable cosmic laws. The revolutionaries of the Paris Commune were “poor peasants driven to uprising by oppression”. They were noble, strong, and beautiful. He used words and described behavior that fit the Confucian model for peasant rebels overthrowing a dynasty that had triggered such events by maladministration. When the Third Republic marched lines of captured revolutionaries to prison and execution, Zhang wept to see them pass. Even if this peasant revolt against an unjust ruler failed, under the Confucian model a different rebellion would someday inevitably succeed.

When Zhang and Chonghou returned to China, they were again surprised by the political environment they found. The Chinese literati had decided in the legation’s absence that the 1870 Tianjin riot was justified, and the French needed to get over it. This opinion contradicted the official government position, making the government look weak (which, of course, it was). Zhang’s superiors pressured him to publish neither the diary of this, his third mission, nor the manuscript he’d drafted talking about the Paris Commune. The literati didn’t need to know that France was too weak, divided, and distracted to respond to the Tianjin riot. They certainly didn’t need to know the outcome of the legation: that China was to pay France an enormous sum in silver. If France’s weakness became common knowledge, the literati would decry the government’s conciliatory posture towards France even more strongly, and the government didn’t need any more trouble.

Zhang would go on to several more foreign postings, but he didn’t get promoted much. His classical education was insufficiently lofty, and the ease with which he picked up foreign customs and attitudes made him suspect in the eyes of senior administrators. In the end, his career simply became obsolete as the Qing civil service system fell apart under the weight of revolution.

At your table, Zhang’s mission makes a great template not for an adventure, but for the interstitial tissue that helps knit adventures together. A crisis necessitates a surprise legation to a distant power. Because of a shortage of talent, the PCs are tapped to help out. Maybe they’re translators or caravan guards or mechanics or general troubleshooters. Throw a couple of obstacles at them while they travel. In my back catalog, I’ve got 25 posts (as of this writing) tagged ‘travel’ that you can mine for appropriate obstacle ideas. As always, posts older than a year are hidden behind a $2/month paywall, but that’s super cheap!

When your PCs get to the foreign power, they find their mission has been overtaken by events. The situation has either changed while they were in transit or was grossly misunderstood. Things are different from what they expected. The new situation kicks off the party’s next adventure! Four options from the back catalog (that are on the free side of the paywall) include

– The emperor is throwing an enormous, important party

– The royal family is squabbling using a secret language

– Workers are revolting against livelihood-destroying machinery

– A pirate has seized the monarchy

The legation’s Commune surprise also works great as a complication. The PCs are going someplace to accomplish a specific task, but when they arrive, they find the government’s been overthrown by a new one, and a third government is in open rebellion against the second! Suddenly the mission looks a lot harder.

And if nothing else, Zhang and Chonghou make really cool NPCs you can stick anywhere. Something wild is going on, and these two diplomats show up totally unprepared!

Source: Qing Travelers to the Far West: Diplomacy and the Information Order in Late Imperial China by Jenny Huangfu Day

And thanks to Patreon backer Colin Wixted for helping me with this one!