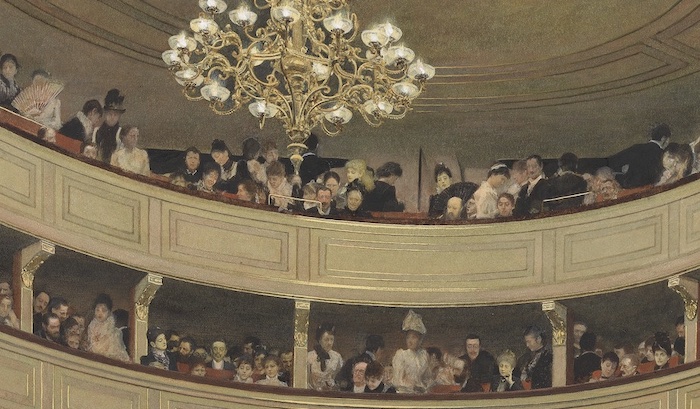

In 1888, the Austro-Hungarian empire was in its decadent final decades. In Vienna, the capital, baroque splendor was on full display. Yet while ‘baroque’ can mean glitzy and overwrought, it also refers to an artistic style then over a century out of date. And that’s late 1800s Vienna: a cultural Mecca that was also the seat of an empire growing more obsolete by the day. Its a great source of adventure hooks! We’re going to look at five drawn from a single year in this glamorous, florid, out-of-date metropolis.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

First, a word about Austria-Hungary. We don’t talk much about it in the U.S. I think that’s because we don’t know how. It doesn’t fit into how we think about nationhood. To oversimplify, an originally-unremarkable German noble family called the house of Habsburg spent centuries arranging the marriages of its children with an eye towards long-term expansion. One by one, titles from outside the family (count of this, duke of that) found their way into Habsburg hands when their male lines eventually terminated: a mathematical inevitability given enough time. The Habsburgs did not conquer many territories. Nor did they consolidate their possessions into a single state. It simply happened that one or more Habsburg heads simultaneously wore the crowns of many nations, chief among which were Austria (since 1268), Hungary (since 1437), Spain (1555-1700), and the Holy Roman Empire (1440-1806). It’s totally valid to speak of each as an independent state, as each maintained its own parliament, laws, and ways of doing business. In the case of the Holy Roman Empire, it maintained many such, not being centralized. But it’s also valid to speak of all these holdings as belonging to a single Habsburg Empire or Austro-Hungarian Empire.

In 1888, the Emperor of Austria was Franz Joseph I. He would remain in that role through most of World War One. A small subset of his separate, non-unified titles includes: Emperor of Austria; King of Hungary, Bohemia, Dalmatia, Croatia, and Jerusalem (the latter in name only); Grand Duke of Tuscany and Krakow; Duke of Lorraine; Grand Prince of Transylvania, Modena, and Parma; Count of Habsburg and Tyrol; Lord of Trieste; and Grand Voivode of Serbia.

This system was stupid. It had been on the threshold of failure for centuries, stumbling from crisis to crisis one step ahead of total disaster. The prime minster of the subset of lands including Vienna even had a word for it: fortwursteln, roughly ‘keep improvising and slogging along’. And when eight centuries of improvisation finally came crashing down in 1914, it took twenty million souls with it. World War One was launched by a Serbian assassin rebelling against this same ludicrous political order by gunning down the empire’s crown prince.

Yet as these lands stumbled towards armageddon, they had Vienna as their capital: beautiful, chaotic, obsolete, and overflowing with genius. This was the city that – in 1888 alone – was home to Strauss, Brahms, Klimt, Mahler, and Freud. It was a city where Austrians, Italians, Hungarians, and Bosnians rubbed shoulders as fellow citizens. The mad foment of the late Habsburg Empire produced gilt and grandeur out of place with a new world of telephones and machine guns. So many contradictions and so much chaos produced wonderful inspiration for adventure hooks.

Our first hook concerns organist Anton Bruckner. He’s best known today as a composer, but in 1888 the 64-year-old Bruckner was having a devil of a time convincing people to care about his compositions. He had some fans, but most people knew him as a virtuoso organ player and a professor of music theory. He was very well-respected, but not for the reasons he wanted to be! It didn’t help that he was something of a country bumpkin, out of place in glorious Vienna. And for whatever reason, the unfulfilled, anxious Bruckner was eager to get his hands on the skulls of great composers!

In June, Beethoven was being reburied. He’d been dug up in 1863 so scientists could study his bones. This was an era where scholars were trying to find relationships between body measurements and the mind; phrenology is the best-known example. In June it was time to put him back in the dirt. But before that could happen, Bruckner barged into the chapel, pushed past a policeman, and picked up Beethoven’s skull. Bruckner took off his pince-nez and clamped it onto the skull’s face while making jokes. The police dragged Bruckner out of the chapel and took back the skull. Bruckner got to keep his glasses.

In September, another famous dead composer, Franz Schubert, was dug up so he could be reburied beside Beethoven. Along the way, Schubert’s sarcophagus was placed in a small chapel. For some reason, Bruckner was invited to this event. Schubert’s skull was taken out and placed on a black cloth so it could be photographed and measured. After the phrenologists finished crawling all over it, Bruckner swooped in to grab the skull. He held onto it until a representative of the mayor gently pried his hands off. But the organizers let Bruckner put the skull back in the coffin, so at least he was the last person to touch Schubert’s head.

At your table the obvious hook is that a fictional NPC based on Bruckner wants more skulls! He might ask the PCs to dig up some more composer skeletons. It would also give your players a reason to make the joke about Beethoven’s corpse de-composing about a hundred times. I would unironically love that. Or maybe the PCs are called in to investigate a rash of grave robberies. Or maybe Bruckner can’t be satisfied with long-dead heads. In real 1888 Vienna, pop idol Johann Strauss was preparing to unveil his Emperor Waltz, composing giant Johannes Brahms was feuding with Bruckner, and future luminary Gustav Mahler was starting his early work. If these composers start turning up headless, you’ll know whom to blame.

Our next hook is drawn from the newspapers. They’ve unhelpfully (for us) altered the name of the story’s embarrassed subject, “Count Walter H.” A visitor called on the count at his chic Vienna Woods villa: a fashionably-dressed American going by Phillip H. Elkins. Elkins represented himself as the chief European representative of American inventor Thomas Edison. He’d heard the count had a wonderful singing voice. Mr. Edison was preparing a phonographic gallery of the great voices of the nineteenth century. Would the count consent to being recorded so his voice could be added to the collection? Obviously, the flattered Austrian agreed.

Mr. Elkins went out to the carriage where, with the help of two of Count Walter’s footmen, he retrieved a heavy machine covered in wires and tubes. The count sang his favorite aria into the device while Elkins carefully managed the advanced machinery. The count then asked Elkins to play back the recording for him. Alas, Elkins explained, such a thing was not possible. Phonographs and gramophones – brand new on the commercial market – could not play this sophisticated recording. Indeed, no such playback machine existed in all of Europe. But Elkins did have a copy of Edison’s blueprints for a device that could play this record and planned to build a few in Europe at some later date.

But the count wanted to hear his voice played back to him! He offered money. Elkins warned that building the machine would take three weeks and 500 florins. Count Walter handed over 250 florins on the spot for work to begin, plus a 50-florin licensing fee to Mr. Edison. Elkins pocketed the money, helped load his machine back into the carriage, and departed. He and the money were never seen again.

An NPC based on Count Walter H. might ask the PCs to catch Phillip Elkins. The count doesn’t care about getting his money back. He needs to restore his reputation after being publicly humiliated. In your fictional setting, build the scam around some new technology lots of people are excited about. This is a really cool place to highlight something distinctive about your setting! Instead of Edison, use some celebrity inventor or wizard you want to spotlight. Talking to your Edison-analogue is an obvious place to start the investigation. She can direct you to local machinists who can make something like Elkins’ fake device, who might be able to direct you to Elkins himself. Maybe Elkins is part of a ring of con artists the PCs can bust. Maybe Elkins’ machine actually does something sinister to the person it’s ‘recording’. Maybe, in a twist, Edison is actually behind the whole thing, figuring that some high-profile scams aimed at targets who can afford it will enhance the technology’s mystique.

Image credit: Sergio Moises Panei Pitrau. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 International license.

Our next hook lies in an asylum for wealthy and fashionable madmen. Professor Maximilian Leidesdorf operated a psychiatric retreat near Count Walter’s villa in the Vienna Woods. His reputation for treatments was such that his clinic could draw its rarified clientele from across the Empire and beyond:

– Emil W., a gambling addict and the son of one of Vienna’s richest manufacturers. He constantly made bets over the most trivial things and would explode at anyone who wouldn’t bet with him. For him, Leidesdorf set up a roulette wheel in the clinic and assigned an attendant to serve as a fake croupier.

– Mr. M., a steamship company director. He became convinced his billiards opponent was an anarchist plotting to assassinate the king of Greece. He attacked the man with his pool cue and was taken away to Leidesdorf’s.

– A fashionable gentlewoman who started stripping in the middle of Mass. As she pulled off her furs and her layers, she preached an incoherent sermon about the imminent Second Coming of Christ and the catastrophes that would precede it. She too was carted off to Leidesdorf’s.

– Alois Bank, a comedian who’d been in the clinic for ten years. He considered himself cured but had no desire to leave. On important occasions he’d perform his comedy routine for the other patients, going through his decade-old material.

– When a multi-millionaire in Philadelphia saw her daughter sink into a dark depression, the Prince of Wales himself recommended the young woman be sent to the professor’s clinic. A doctor built for her there a healing machine that emanated blue rays, weird noises, and “ether” (presumably the space-stuff, not the gas). Sitting in it didn’t seem to help the patient much, so instead Leidesdorf stuck to water immersion, electrotherapy, and primitive psychoactive drugs. Then a custody battle erupted between the patient’s husband, a Swedish diplomat, and her wealthy widowed mother. It was all very dramatic – and very expensive!

– And though he left in 1885, the clinic once employed a young Sigmund Freud as a “nerve doctor”. That’s a fun coincidence!

At your table, a fictional version of Professor Leidesdorf might receive an anonymous note claiming that an unidentified resident of the clinic was merely faking her illness as cover to escape her creditors (or even assassins!). If true, such a scandal would be bad for business. Your Leidesdorf-analogue might ask the party to quietly snoop around and see if any of the patients are faking their symptoms. Also, who sent the note and why?

The next hook is that the crown prince of the empire is secretly writing newspaper editorials on subjects the court would rather not be touched. Crown Prince Rudolf was handsome, charming, instantly likable, and beloved by even the poorest Viennese. He was known to be reform-minded and a supporter of civil liberties. This put him at odds with his cautious, authoritarian father. Consequently, Rudolf was kept as far away from actual power as possible. His many titles and offices permitted him zero authority. Smart monarchs make sure their successors get the opportunity to practice at ruling. Franz Joseph I permitted his son none of that.

So Rudolf made his voice heard anonymously in print. He couldn’t publish under his own name. The imperial censors kept a tight leash on the press. Any piece by the popular crown prince that criticized government policy would surely be pulped. Neither could Rudolf just stroll down to a newspaper office to submit a manuscript and ask that it be published anonymously. He was constantly surveilled by the secret police. If he went himself, the censors would catch wind of it.

So Rudolf played spy games to submit his reform-minded editorials. He gave his papers to a reliable old servant named Nehammer. Nehammer got on the horse-tram, then changed trams twice to throw off any tails. He took the tram to the home of the daughter of the publisher of Rudolf’s preferred newspaper. He announced himself at the door as the young woman’s masseur. Inside the house the publisher, Moritz Szeps, was waiting. Szeps copied Rudolf’s papers by hand. He sent the new copy by messenger to the newspaper’s office and returned the old copy (in Rudolf’s handwriting) to Nehammer, along with some information from the newspaper’s correspondents that the censors would not permit to be printed.

At your table, piercing a spy game is a fun adventure hook. I would have the PCs be approached by Rudolf’s wife, Princess Stéphanie. She knows he’s up to something, but she can’t figure out what it is. The real Rudolf kept mistresses. In your fictional setting, the NPC you base on Stéphanie might have less to fear. In any case, the PCs have to watch Rudolf without attracting the notice of the secret police who are doing the same. If they follow his servant to a particular house, they might deduce what’s happening inside by sneaking in, by tracking the next messenger to the newspaper office, or by checking the ownership records to see it’s owned by a newspaper family. Then the PCs have to decide what they do with the politically-sensitive information they’ve gathered.

Finally, though brief, I couldn’t leave out Johann Pfeiffer, the “King of the Birds”. He was a street performer in Vienna’s nicer districts. He kept a huge cage topped with a baroque dome and filled it with parrots he taught to repeat lines from plays. He specialized in works that would soon open at the nearby Court Theater, but he changed it up depending on the public’s mood. The parrots would squawk their lines and he’d reply appropriately, acting out little vignettes. He kept a box full of masks so he could swap out what character he was playing. On the box was written in gold, “Life is serious but art is gay”. Pfeiffer would later be arrested on the suspicion that his birds spoke treasonous truths. At your table, how the birds learned these truths (and why they’re so fond of treason) is an A+ adventure hook.

Check out Shanty Hunters, my award-winning TTRPG about collecting magical sea shanties in the year 1880, then singing them at the table with your friends. The lyrics of the shanties come to life and cause problems for you and for the crew of the ship you sail aboard. It’s up to you to find clues in the song and put things right!

–

Source: A Nervous Splendor: Vienna 1888/1889 by Frederic Morton (1979).