For the upper classes, the early 1800s in Britain were an elegant and glamorous age. This is the time of Bridgerton, Emma, and Pride and Prejudice. In London high society, it was an era of lavish balls, fabulous outfits, and not thinking too much about the ongoing Napoleonic Wars or the growing poverty in the street outside. Two remarkable people give us lenses through which to view this society: the courtesan Harriette Wilson and the dandy Beau Brummell. The former wrote a scandalous tell-all memoir, while the latter refused to do the same despite ample reason to the contrary. The memoir that was and the memoir that wasn’t both make wonderful plot hooks easily adapted to your ongoing campaign.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Robert Nichols. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Robert, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Harriette Wilson (1786-1845) was born Harriette Dubochet, the daughter of a clockmaker with a shop in the fancy Mayfair neighborhood of West London. Her sister caught the eye of an aristocrat and became his paid mistress. It was so much fun (and so much better than marrying a tradesman) that Harriette followed suit as soon as she turned fifteen. She made herself interesting, entertaining, and sexy. She taught herself the classics. And she used the fact that some aristocrats chased her to make herself seem still more desirable to other aristocrats. Within a few years, she could charge large sums just for an initial meeting with a man – always in public, where she could escape if she picked up bad vibes – to discuss terms for future public dates and private liaisons.

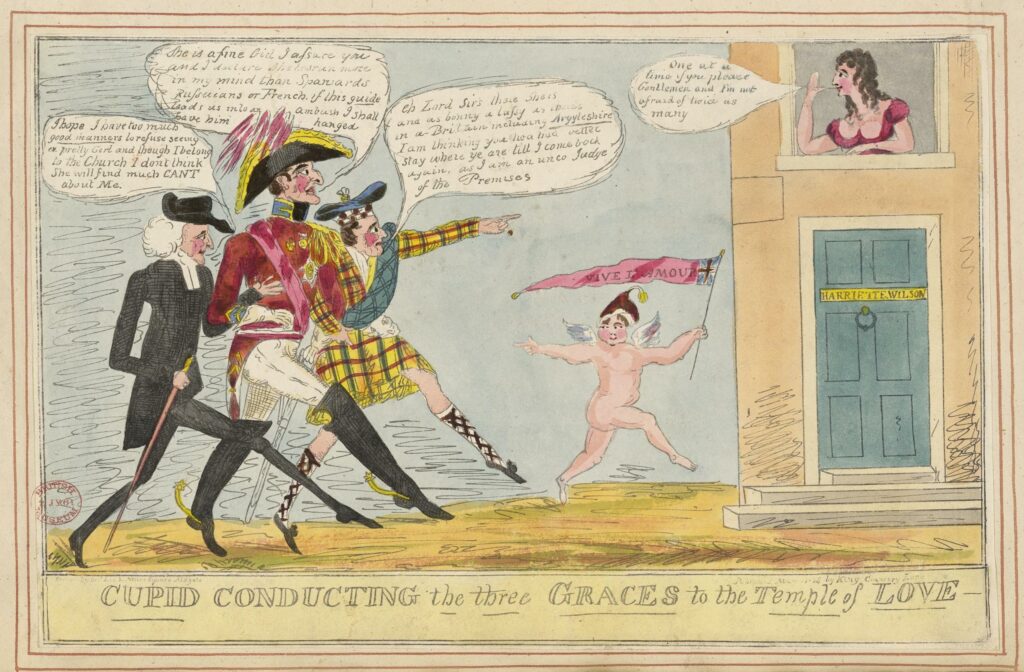

Wilson’s list of confirmed and alleged clients is a who’s who of the peerage. Dukes, the first sons of dukes, and members of Parliament feature prominently. The most notable was her long-term, on-again-off-again client the Duke of Wellington, the defeater of Napoleon and future Prime Minister. I really cannot stress enough how skilled Wilson was at staying in demand and how luxurious a lifestyle she maintained. Sometimes she’d be a kept woman, living with a blue-blood for a few months while he visited his country estate. Other times she’d live in London and maintain many paid relationships at the same time, presumably carefully scheduling which night she was out with whom so as not to double-book herself.

Wilson’s opinion of her place in society was high, while her opinion of her own character was surprisingly frank. She once proposed to meet with the Prince of Wales: the regent and ruler of the empire, his father King George III having been indisposed by madness. She did this by letter, being in Brighton with another client. The Prince replied by letter that he’d be happy to meet with her if she came to London. She wrote him a nasty reply, claiming that her status was such that she should expect the Prince to travel to her. The Prince did not bother to respond. Still, in her memoirs, Wilson wrote that she did not think herself a particularly pleasant or good person. Given that we’re all the heroes of our own stories, I find this kind of self-criticism admirable.

At age 34, Wilson’s outstanding career took an interesting turn. The son of the Duke of Beaufort was hopelessly in love with her and proposed marriage in a letter. The Duke forbade him from pursuing the relationship further. Whether Wilson actually intended to marry the Duke’s son or not, the letter gave Wilson grounds to sue him for breach of promise. A lawyer advised her that she could claim damages equivalent to about two million dollars today. The Duke bargained her down to fifty thousand modern dollars per year, provided she agree to move to Paris. The wars being over, ritzy social life in Paris and in London was much intertwined, and Wilson continued her glamorous life (and professional work) on the continent. But then the Duke’s son got married for real and the Duke cut her off. He wasn’t the only one. Many of Wilson’s other clients had promised her comfortable annuities for the rest of her days – when she was young and pretty. Now that she was (gasp!) 34, these promises were conveniently forgotten. So Wilson decided to get back what she was owed. She wrote a book.

The Memoirs of Harriette Wilson: Written by Herself contained scandalous stories of her affairs with the great British men of the age. Before the book went to print, she reached out to every man in it and offered to leave him out – if he’d pay for the privilege. Most refused the blackmail. The Duke of Wellington’s response was “Publish and be damned!”

The social fallout was real. By the time of publication, Wilson had been a courtesan for twenty-four years; many of the men she wrote about had long since outgrown their youthful wildness and were sober, respectable statesmen whose reputations were damaged by the revelations in Wilson’s book. Lord Craven, her very first client when she was a teenager, was a bore. Frederick Lamb was sexually violent. Colonel Berkeley was an outright sexual predator. Lord Lowther was filthy, a drunk, and cheap. Lord Deerhurst was the stingiest of them all, despite his wealth. He lived in squalor, refused to buy any light but cheap stinking tallow candles, took girls out on ‘dates’ to the meanest inns, and cheated at tolls on the toll road, even getting into fights with turnpike keepers over it. Only Lord Ponsonby, the handsomest man in England, escaped Wilson’s pen. She’d spent three years desperately in love with him, and he never returned the favor.

Wilson’s book was a sensation. In the first year, it was reprinted thirty times. The book made her persona non grata in high society, but it also made her wealthy – and, for the first time, independent.

The career of high-society dandy George Bryan ‘Beau’ Brummell (1778-1840) also ended with him booted out of the upper crust, but in a very different manner. He was a perplexing figure. The only way I can make sense of him is as a performance artist – but one whose oeuvre was the abstract concept of ‘being fashionable’. He was no aristocrat. His grandfather was a valet who made a lucky connection, which let Brummell’s father get some government sinecures and marry a rich woman. That meant Brummell could go to a good school, learn all the right manners, and meet all the right people. Brummell spent five years as an officer in the Army (because it was the fashionable thing to do), somehow without ever being sent overseas to fight in Britain’s endless wars or being posted anywhere less fashionable than London. After Brummell left the Army, this charming young man with no noble blood or deep fortune somehow made himself the most sought-after guest in London high society. The Prince of Wales fawned over him. A party was considered a failure if Brummell didn’t make an appearance.

Brummell’s deepest impact was in clothing. English men’s fashion in the 1700s was all about ostentation: bright colors, expensive materials, diamonds and ornaments everywhere. While men’s fashion had already started to trend away from this, it was Brummell who codified its new form: dark colors with white accents, few (if any) decorations, and a very tight fit. Brummell, the performance artist, wore clothes so tight he had to be manhandled into them and pants so tight he often couldn’t sit down. He claimed to have his jackets made by one tailor, his waistcoats by a second, and his trousers by a third, each an expert in their field. He also claimed three barbers: one for the sides, one for the front, and one for the top. He refused to walk to parties lest he get dirt on he shoes. He had to be carried in a litter. He introduced a fashion for white-topped hunting boots – useless for actually hunting in, since the white top would be swiftly ruined. And his real singular invention was the starched cravat, which took him hours every day to put on just right. Select invitees would crowd into his apartments to watch him do it. This is not an art that is to my tastes – but I can’t deny that it’s performance art.

Brummell didn’t really do anything other than be fashionable. He had no profession, nor did he have any rents coming in, since his family owned no estates. Even at parties, he would just show up, chat with a few people he was already friends with, then leave early. He pursued neither women nor men. He was renowned as a wit, yet none of the witticisms that have come down to us seem clever or funny. They’re cruel, if anything. Brummell just sort of… existed. Fashionably.

That was Brummell’s downfall. He spent his whole life being the best at a fabulously expensive game (or art form), without access to the vast incomes the game presupposed. For that, he had to rely on his friends.

Aristocratic attitudes towards money in Regency England were bizarre by modern standards. Aristocrats – hereditary members of the landed and titled nobility – inherited huge tracts of land and extracted rents from the tenant farmers who had lived on that land for generations. Money was a passive thing; rent income came as predictably as the tides. The rise of a new moneyed class made aristocrats treat wealth even more passively. Businessmen and bankers had amassed fortunes often greater than those of the richest dukes. But aristocrats still had to see themselves as better than their wealthier counterparts. Part of how they accomplished that was by not being hung up on money, unlike those gauche businessmen who never thought about anything else. For these aristocrats – especially the men – wealth had always been and would always be. To pay too much attention to it was crass. It was this attitude that kept Brummell afloat for years.

Whenever Brummell ran short of money, he could send a letter to one of his blue-blooded friends, and they would happily send some over, even if they were deeply in debt themselves. Some of Brummell’s benefactors had debts many times larger than their entire annual incomes. But they always found a few hundred pounds to send to their old pal Beau, the most fashionable man in England. To do anything else would be uncouth, the sort of thing a banker might do. This game worked for decades before even Brummell’s richest friends started ignoring his letters. His debts ballooned. His aristorcratic pals couldn’t be arrested for debt, but Brummell could be. He fled to France, one step ahead of his creditors. He succeeded at maintaining his lifestyle in France for some time before sliding down the ladder into poverty.

Brummell was approached by publishers offering to pay him for a tell-all memoir. The sums were large: hundreds of thousands of dollars in today’s terms. Brummell refused them all. He would rather go to debtor’s prison than betray his friends.

At your table, obviously Wilson and Brummel make great inspiration for fictional high-society NPCs. If you can befriend them (perhaps via a cash donation), they can introduce you to absolutely anyone rich and important in your setting. Get on their bad side and they can call in favors with generals, nobles, and politicians. Stay on their good side and they can supply you with gossip that – at this rarified level – probably crosses the line into national intelligence. God, imagine turning one of them into a spy!

But it’s the memoirs that most jump out at me: the memoir that was and the memoir that wasn’t. Procuring or suppressing a memoir inspired by Wilson’s or Brummell’s is one heck of an adventure hook. An unpublished copy of either memoir is a treasure trove of blackmail. In a political game – or even if you just have one player who wants to do political things with her PC – such a book is a terrific reward or piece of treasure. Just the rumor of the book existing is a plot hook. PCs owning an unpublished tell-all by an authoritative source will have a significant leg up in pursuing their political aims. Party patrons with something to hide might want to send the PCs to find and burn a copy. But once the party finds it, will they follow through?

The book’s not a magic bullet. Note that Harriette Wilson tried to blackmail money out of her clients with it and mostly failed. So while maybe you could use it to blackmail a politician into changing her vote on a bill she could go either way on, you probably couldn’t get her to change parties or give you money. From a gaming perspective, that’s good! The book gives the PCs more power, but there are still limits. And if the PCs lean on the book too hard, eventually they’re going to be told to “publish and be damned.”

Setup: If someone influential believes the PCs are discreet, one Lady Feeny approaches the party. She says that she’s heard they can do confidential work and keep quiet about it. The legendary dandy Beau Brummell, currently living in exile, is planning to write a scandalous tell-all memoir. She wants the PCs to acquire the unpublished memoir and bring it to her so that she can prepare the court for what Brummell is going to reveal.

If the PCs don’t have a reputation for discretion, they are approached instead by Magog, a fence and ne’er-do-well. He tells them that he has a buyer (secretly Lady Feeny) lined up if they can acquire Beau Brummell’s scandalous memoir. He’ll split the money from the sale with them.

Either way, the quest-giver provides Brummell’s address in a luxurious foreign city and makes clear that there are still many people at court with a soft spot for the dandy. The party is not to hurt him or anyone he cares about.

Situation: Beau Brummell is not preparing a scandalous tell-all memoir. If questioned about it, he’s offended. He’d never betray his friends, no matter how far he’s fallen! But he is living with a platonic roommate, Harriette Wilson, and she is preparing such a memoir. Somewhere along the way, the rumor mill confused the two roommates. Brummell supports his friend’s authorial ambitions; no one owes him anything, but a lot of people made Harriette promises, and he feels she’s getting back what’s hers.

Brummell and Wilson live together in a two-story house full of fancy but threadbare clothes and once-nice furniture. Brummell leaves the house daily to get a drink at his favorite coffee house. Wilson leaves the house weekly to meet her lover, Gog (more on him in a minute). Otherwise, Wilson is mostly downstairs working on her memoir.

Wilson only has one copy of her manuscript. If it were to vanish, it would take her three months to recreate it from scratch. She keeps unfinished pages downstairs. Most of the manuscript is upstairs in her bedroom in a lockbox decorated with images of putti or cupids: as many putti as there are PCs. If anyone opens the lockbox by any means without saying the password “Ponsonby”, the putti detach from the lockbox and fight whoever’s nearby. A PC struck by a putti’s arrow must make a Wisdom save or turn on their friends for one round.

In addition to that security, Wilson has become quite close with Gog, the head of a local gang and hated half-brother of possible quest-giver Magog. Gog is partial to Ms. Wilson; she’s a dear friend and favorite lover. Gog keeps a gang initiate loitering near Wilson’s and Brummell’s house 24/7, ready to summon the gang to throw down if he spots trouble.

Outcome: This is a complicated situation and can go any number of ways. Don’t be afraid to have Brummell or Wilson walk in on the PCs mid-robbery and be shocked. They’re fun characters and it’s worthwhile to give the PCs a chance to interact with them. If the PCs manage to get out of the city without trouble, Wilson will soon realize what’s happened, Gog’s gang will ask around after out-of-towners, will find out about the PCs, and will pursue the party on horseback. The gang, accompanied by Wilson, might catch up with the party in the countryside. Neither Wilson nor Brummell will ever choose to get involved in combat; they’re talkers, not fighters.

If the PCs get their hands on the manuscript, will they actually want to deliver it to the quest-giver? The memoir is a powerful piece of blackmail, and the party might prefer to hang onto it and use it themselves, even if it costs them their relationship with Lady Feeny or Magog.

I wouldn’t be surprised if I write a lot of posts about Regency Britain in the coming months. I’m in the research phase of my next tabletop RPG: Ballad Hunters, which is about collecting and combating magical folk ballads in 1813 England and Scotland. The songs of the common people are coming to life and spreading grief, betrayal, and murder! Play as folklorists employed as agents of the government, sing historical ballads with your friends, and overcome the perils hidden in these wonderful old folk songs.

Since I’m in the research phase, that means reading books about Regency England and Scotland, and that means I’ll be bumping into blog topics. Since I won’t have to do extra research to turn them into posts, I’d be a fool not to write them up and share them with you! It is weird that the first example of this was very much not about the ordinary people Ballad Hunters focuses on, but hey – you dance with who brung ya, right?

I’m about 80% of the way through the 305 ballads (and thousands of variants) compiled in the late 19th century by Francis James Child. The further I get in the process, the more excited I am about this project. This RPG is going to be easy to run, easy to play, and super fun!

–

Source: An Elegant Madness: High Society in Regency England by Venetia Murray (1998)